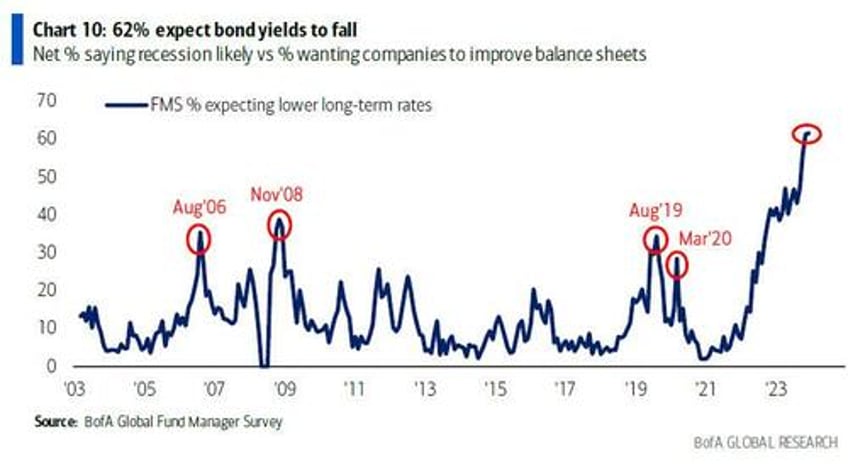

One week ago we explained why the "most consensus trade" of 2024 - namely long Treasurys in expectation of lower yields - will blow up in the market's face. Now, it's the turn of Bloomberg Markets Live reporter and strategist, Ven Ram, to do the same.

The trouble with Treasuries after their humongous rally of the past two months is that they have priced in all the good news. That is especially so at the front end of the curve, which sets them up for a reality check as traders return to their desks this week to confront ISM manufacturing data to Fed minutes to non-farm payrolls.

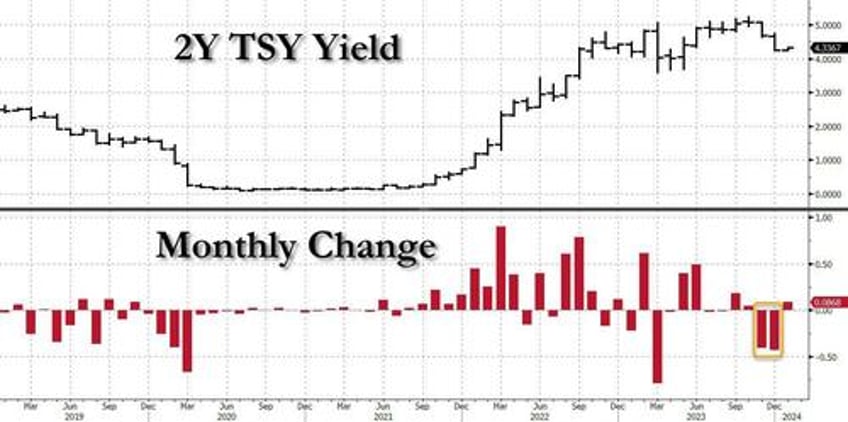

Two-year Treasury yields slumped almost 45 basis points just last month, making it their best December in more than two decades. Looking at the more than 80-basis point decline in yields over the past two months, one is reminded of the steep decline in the first quarter of 2020. Back then, yields were sliding so imperiously in response to the pandemic that the Fed slashed its benchmark rate by a phenomenal 150 basis points in just one month — March — that year.

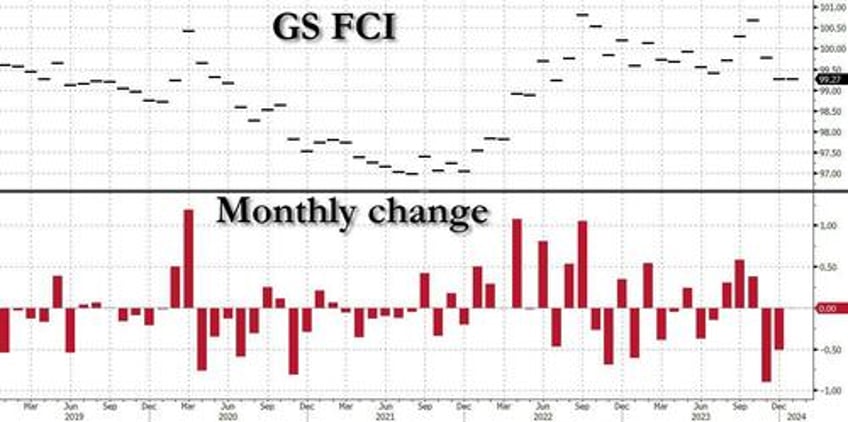

Except that the US economy now is in a far different shape, and in zero need of any rescue hand from the central bank. If anything, the inordinate loosening of financial conditions since the release of the December dot plot has perhaps had the effect of a de facto rate cut or two.

If the street’s forecasts of what is to come this week are right, we will see an improvement in the ISM manufacturing numbers for December, continued expansion in the ADP as well as non-farm payrolls data and a jobless rate still well below 4%. None of them spells like an imminent rate cut to me, which makes it more likely that the next 25-basis point move in front-end Treasuries will be higher rather than lower.

The Fed’s minutes will be keenly parsed for one cue more than any other: about when its members thought a rate cut could start. After all, Chair Jerome Powell commented at last month’s review that the policy committee discussed the timing of policy easing. Consistent with the pushback from several Fed officials afterward, I am inclined to think that March wasn’t what they were thinking — another factor that is likely to set up two-year notes for a correction.