By Tor Vollalokken. The blog appeared earlier this month as an op-ed in Dagens Næringsliv. Tor Vollalokken enjoyed more than fifteen years as an Investment Banker and thirty years as an independent analyst and advisor to sovereigns, hedge funds, fund managers, family offices, and energy companies worldwide, focusing on Scandinavian currencies.

NOK’s structural challenge

The weakening of the krona in recent years is, for me, explained through two structural factors:

1. A large capital outflow in kroner is caused by an import surplus in the goods trade balance (the petroleum sector is left out, since it is essentially a currency balance).

This negative krone balance has been there for a long time, though has accelerated somewhat in recent years. Both the Ministry of Finance and Norges Bank are, of course, aware of this negative balance, but they probably see the funding of the budget deficit - which is a krone inflow - as matching this krone capital outflow – and to a large extent it has.

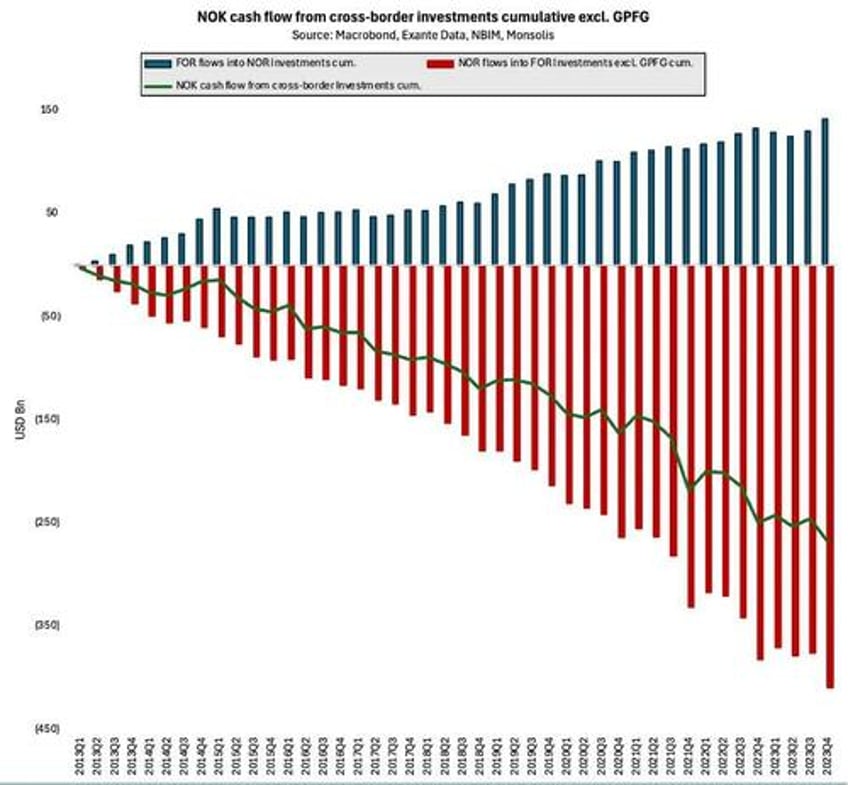

2. The relatively new problem lies in the securities balance, where over the past four years Norwegians have invested significantly more in foreign equities and bonds than foreigners have in Norway.

This has resulted in a large krone capital flight out of Norway, so much that it explains the broader part of the krone's weakening.

Some of the investments Norwegians do abroad are currency hedged, and this reduces the krone output somewhat.

The reasons foreigners do not invest more than they do and, why Norwegians invest as much abroad as they do, are certainly several.

I am not a politician, and therefore I do not have any opinions about it. I am only making a few assumptions about whether changes in taxes, regulatory conditions and ambitions can be expected, that will either strengthen or weaken the krone. As I see it today, such changes are few and probably for some time into the future. I therefore assume that the structural capital outflow in kroner in the next few years will continue at approximately the same level as what has been seen since 2020, and it will therefore be a source of further krone weakening.

Policy tools

Norges Bank only has the policy rate as tools to achieve its inflation target, and has also shown no desire to use other tools.

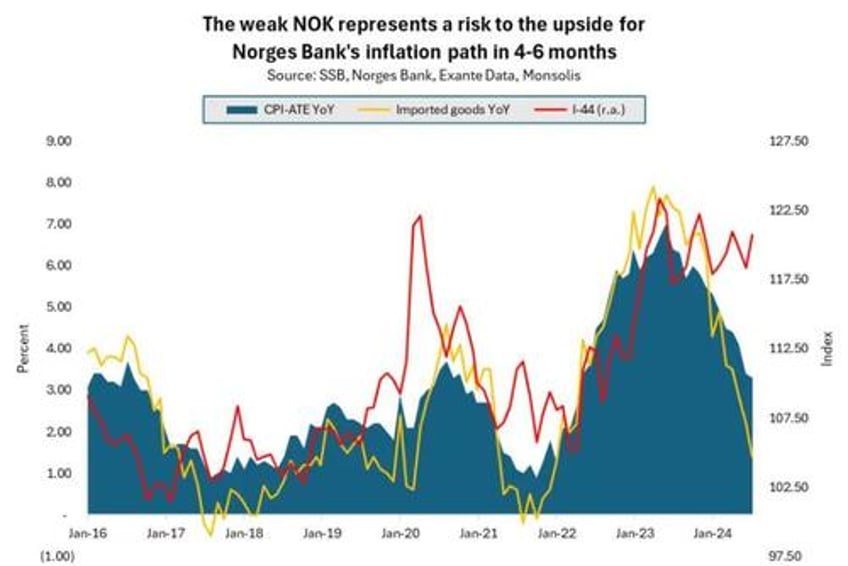

It is critical for the inflation target that the krone does not weaken further. The krone will probably have to regain some ground from its current level, for Norges Bank's inflation projection in September not to be adjusted upwards.

This summer I expressed in “Dagens Næringsliv” that Norges Bank is "cornered." By that I mean that it will be the krone exchange rate that determines the future interest rate level in Norway. I think this is unfortunate. The interest rate should be set based on the inflation target and desired developments for business and households, including achieving high employment.

The krone's structural problem can be fixed.

This can happen through political decisions that stimulate increased investment in Norway from abroad or reduce Norwegians' appetite for foreign investment. Again: It's not my table.

Alternatively, speculative investors can buy the kroner as a counterweight to the kroner capital outflow. I would have great reservations in my clients becoming a solution to the krone's speculative problem. They are big enough in total for a short-term solution, but with a strong profit motive, they will only buy krone when a number of parameters are in place, and the krone interest rate is only one of them.

Fed to the rescue?

The most important incentive is actually the outlook for the dollar and the dollar interest rate - which is completely outside Norges Bank's control. Should my clients first buy the krone, and then choose not to sell the krone again after an appreciation in the exchange rate, they would want to be paid well. That means an interest rate differential to currencies of trading partners, which we are quite far away from today.

I think it is sad that Norges Bank makes itself dependent on speculative investors. The krone's structural problem should not be solved by them.

Norges Bank needs instead extended use of measures to prevent an undesirably high level for interest rates. I have therefore proposed that a small part of the Oil Fund to be currency hedged, in order to neutralize the krone capital outflow. Its purpose is to ensure far less volatility in the krone exchange rate and an exchange rate level that does not threaten the inflation target or financial calculability for businesses and households.

The oil fund is a resource that no other country has. It is more than 20 times Norges Bank’s currency reserves. Lack of success for currency interventions on previous occasions or for other countries is therefore, in my opinion, not very relevant.

Not expanding the use of instruments means while not setting interest rates at uncomfortably high levels means Norges Bank relying on other central banks cutting interest rates – and a lot.

In practice that is monetary policy largely based on luck.