The biggest bankruptcy in U.S. trucking history could occur in the coming days when the nation’s third-largest less-than-truckload carrier, Yellow Corp., files. The company ceased all operations at noon on Sunday, and leadership representing its Teamsters workforce said it had been notified of a pending bankruptcy filing.

The company is still shopping a small 3PL unit, which may delay a filing. However, it laid off most of its nonunion workforce last week and told union employees on Sunday afternoon not to show up.

While the Nashville, Tennessee-based company saw operations deteriorate rapidly in recent months as it unsuccessfully attempted to push through operational changes with its union workforce, its ultimate failure was anything but sudden.

Bankruptcy filing years in the making

A series of large LTL and other acquisitions in efforts to transform Yellow into a global transportation and logistics leader, the ambition of former Chairman and CEO William “Bill” Zollars, were the catalysts for an eventual downfall.

In 2003, Yellow acquired Roadway in a $1.1 billion deal and then leveraged up in 2005 to acquire USF for $1.47 billion. The goal was to emerge with a command position in the LTL space, allowing the company to leverage larger scale into greater operating and cost synergies.

A much bigger organization with a debt-laden balance sheet, the company took on the YRC Worldwide moniker in 2006 as it had become a holding company for numerous transportation and logistics brands operating in more than 70 countries around the world. In that year, it would see its revenue increase more than threefold since the buying spree began to nearly $10 billion, with earnings per share of roughly $5, or $277 million in net income. That would be the financial pinnacle for the company as a freight recession would take hold that year, followed by a near collapse in financial markets two years later.

However, YRC continued to grow through the freight downturn and with a more cumbersome debt profile in place.

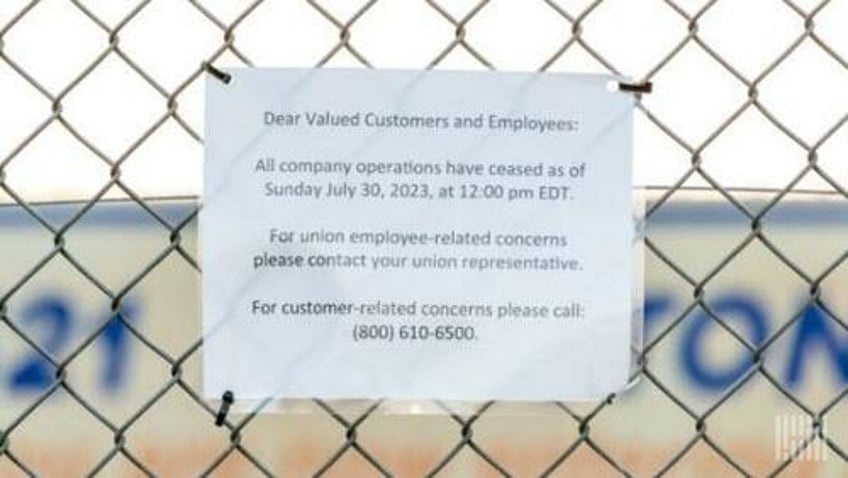

A sign posted on terminal gates on Sunday. (Jim Allen/FreightWaves)

Further expansion of its logistics unit occurred in China with the 2007 acquisition of Shanghai Jiayu Logistics. This further fueled the company’s global growth initiatives. The deal complemented its existing freight forwarding and logistics joint ventures in China, which were established in 2005.

Failure to integrate acquisitions and its national LTL freight network (Yellow and Roadway’s national networks weren’t integrated until March 2009) along with its debt burden left the carrier bloated entering the Great Recession. Matters were further compounded by internal service issues and a rapidly declining freight environment, which was highlighted by fierce price competition as some carriers sought to hasten YRC’s demise by underbidding freight.

The leverage proved to be too much and nearly led to a bankruptcy filing in late 2009.

Debt-for-equity swaps, wage concessions and other financial reengineering

By the end of 2009, YRC was in a perilous position. It had to find a solution for pending debt payments and appease its union workforce, which had already consented to reduced wages. YRC was also tasked with attracting freight to its network as competitors underpriced the company and its customer base sought alternatives as both groups were planning for the carrier’s exit.

After months of credit agreement amendments and extensions from its lender group, YRC was finally able to craft a $470 million debt-for-equity deal in the closing hours of 2009. The deal deferred interest and fee payments to lenders through 2010 and provided the company with access to $160 million in liquidity under its revolving credit facility. The transaction wiped out existing shareholders, including union stakeholders, leaving former bondholders owning 94% of the company’s outstanding shares.

That deal was preceded by two rounds of wage concessions from union employees. In early 2009, the union agreed to 10% wage cuts in exchange for a 15% stake in the company. Later in the year, another round of wage cuts, this time an additional 5%, as well as an 18-month cessation of pension fund contributions, would be required to get the debt-for-equity deal done.

The following year, those wage concessions would be extended into 2015 (and eventually into 2019), and the company’s new pension contribution rate would be just 25% of the rate in place in 2009 — all part of Zollars’ final restructuring, which concluded in the summer of 2011. The union’s equity stake would increase to 25%, and it would get a second seat on the board in exchange. The day before the new deal was approved, YRC said Zollars would step down upon its completion.

The 2011 restructuring included $100 million in new capital for the company along with increased liquidity under a new $400 million loan. The debt-for-equity swap left existing shareholder positions reduced to just 2.5% of the outstanding stock.

That would cap Zollars’ career at the helm. He left the same day the transaction was completed, replaced as CEO by former Yellow Transportation head James Welch.

Zollars’ compensation (including cash, stock, changes in pension valuation and perks) totaled $2.5 million in the restructuring year of 2009. He earned more than $12 million in the three-year period ended 2009.

’09 restructuring was only the beginning

Saved from bankruptcy and with a little breathing room, YRC accelerated its corporate overhaul, which began in late 2009 as a bankruptcy filing was looming. Those efforts included divesting non-LTL offerings.

In late 2009, YRC unloaded its dedicated unit and in 2010, the company sold a stake in its logistics operations to private equity to provide incremental liquidity. In 2011, the carrier sold its truckload operations, Glen Moore, to now-defunct Celadon, and in 2012, it sold its stake in Shanghai Jiayu Logistics to its joint venture partner.

Other liquidity improvement measures were required along the way, including selling and leasing back facilities and reducing capital expenditures on equipment. Reverse stock splits would be required to prop up declines in the share price as a result of the equity dilution. The company completed a 1:25 reverse split in 2010 and a 1:300 split in 2011 to comply with Nasdaq listing requirements for shares to maintain a $1 level.

Facing debt maturities, Welch would complete a recapitalization that again included debt for equity in 2014 after tumultuous but ultimately successful negotiations with the union and the lending group. That transaction would relieve $300 million in debt and pave the way for the company to refinance $1.1 billion in debt, providing it with a more stable capital structure for a while.

However, years of neglecting to fund fleet and terminal upgrades led to higher operating costs and service inadequacies compared to peers, fueling a cycle of lower yields and continual underinvestment in the network. Its industry-lagging service scores — dead last among national providers — forced it to become a low-cost provider. Its inability to appropriately charge for the freight it hauled left it barely covering operating expenses in most quarters and booking losses when accounting for interest expense and other items.

In 2019, it was able to negotiate a collective-bargaining agreement that provided it flexibility around job classifications, work rules for part-time employees and the use of purchased transportation. It was also allowed the use of box trucks in LTL operations with non-CDL drivers. Teamsters would get a pay bump of 18% in aggregate throughout the five-year term (essentially a clawback of what they had given up), the restoration of one week of vacation and an increase in the contribution rate to health and welfare benefits.

The new labor deal also laid the framework for a broader overhaul that later became known as One Yellow, in which the carrier began consolidating its four LTL operating companies, closing redundant service centers and altering work rules for some employees, among other restructuring initiatives.

The same year, YRC executed a $600 million term loan refinance, which lowered the interest rate, provided additional liquidity and offered less restrictive covenants on a portion of its debt. The deal also extended the maturity by two years to June 2024.

The more favorable flexibility in its debt profile would be relatively short-lived as the industry was about to endure a COVID outbreak and subsequent lockdowns, which negatively impacted even the strongest carriers.

Controversial $700M Treasury loan not enough to save the ship

In short order, Yellow (officially renamed in 2021) blew through a $700 million infusion from the government in the form of a COVID-relief loan. The program was established shortly after the outbreak to help companies bridge liquidity gaps directly related to lost business from stay-at-home mandates.

Numerous trucks were parked Monday at a Yellow terminal in Houston. (Jim Allen/FreightWaves)

The first tranche of the loan was $300 million, which was used to clear the deck of the company’s immediate cash needs. It covered previously delayed health care and pension plan contribution payments, lease payments on equipment and real estate, and even interest payments on its other debt, among other items.

A $400 million second tranche was used to fund capital expenditures, largely the purchase of tractors and trailers, which received considerable scrutiny from industry participants. The thought on the part of the government may have been, “In for a penny, in for a pound.” Yellow estimated it would save $10,000 to $12,000 per tractor annually running newer models, and that the upgrades would be the key to reaching longer-term financial stability.

In total, the company replaced roughly 2,400 tractors (17% of the fleet) and 3,600 trailers, and it purchased 600 rail containers — executing roughly three years of tractor capex in a 15-month period. However, the new loan raised its total outstanding debt to nearly $1.6 billion from $880 million at the end of the 2020 first quarter (the last update prior to the loan announcement).

The Treasury’s issuance of the loan in July 2020 has been heavily scrutinized since. An oversight commission concluded recently there were many shortcomings in the decision-making process used to issue the loan.

A key concern all along was the company’s “precarious financial condition” prior to the pandemic given its history of operating at a loss and its poor credit ratings. Yellow’s financial profile and the Treasury’s “less favorable” lien position, compared to the company’s other creditors, present “significant” default risk to taxpayers, the commission found.

Yellow qualified for the loan under a Treasury-created “catch-all” category — “critical to maintaining national security.” The carrier was thought to handle 68% of the Defense Department’s LTL freight at the time, a number that the commission later estimated to be only between 20% and 40%. The commission also took issue with why LTL service couldn’t be handled by another carrier and why a backup plan for service wasn’t in place in the event Yellow shut down.

However, the commission ultimately acknowledged the loan program lacked established guidelines and underwriting was done on the fly as government authorities were required to move quickly to provide emergency liquidity. It provided future remedies should the need for another crisis-induced lending program arise.

At the end of the 2023 first quarter, Yellow owed the government $729.4 million, including capitalized interest. It had made total cash interest payments of $59.6 million by the end of May, according to a company representative.

In addition to collateral for the loan, the government received a 30% equity stake in Yellow, which would likely be wiped out if it files bankruptcy. Yellow’s two top-paid executives earned more than $6 million combined in total compensation the year the Treasury loan was issued.

No change of operations, no Yellow

In the end, Yellow’s inability to get a deal done with the union would prove fatal. Months of back and forth proved fruitless.

Running out of money and options, Yellow sued the union for breach of contract, saying the Teamsters didn’t have the right to reject the change of operations it asserted was vital to its survival. The company said the union also had dragged its feet in coming to the bargaining table when it was well aware Yellow would soon be out of funds.

Throughout the process, the union maintained it had already given enough in the form of billions in wages, benefits and pension concessions. It also said it wouldn’t allow Yellow to jump the line and rush negotiations as it was working on other labor deals with closer expiration dates. It offered to begin its normal collective-bargaining protocols, likely in August, or see the current contract through to its March 31, 2024, expiration.

Missed benefits payments to health, welfare and pension funds managed by Central States put the final nail in the coffin. The delinquency allowed the Teamsters to issue a strike notice, which spooked customers and brokers into accelerating the rate at which they were pulling freight out of the carrier’s network.

“The board members, especially those who represent the Teamsters, have not done service to the members or to the company,” Satish Jindel, founder of transportation advisory firm SJ Consulting Group, told FreightWaves.

He also faulted Yellow’s leadership for not taking pay cuts when it was desperately seeking concessions from the Teamsters.

“The board and the executives should have announced taking cuts in their compensation before asking for any accommodation from the rank and file,” Jindel said. “As they say — ‘leading by example.’ The failure of the company cannot be put at the feet of the Teamsters.”

The bankruptcy would mark the largest filing in U.S. trucking history. The last major LTL closure was Consolidated Freightways, the third-largest carrier in 2002 when it filed. That company was generating roughly $2.3 billion in revenue with 20,000 employees (14,500 of them Teamsters).

Yellow had 30,000 employees, including 22,000 Teamsters.