US households are becoming the buyer of last resort in Treasuries, meaning yields may need to rise by as much as 1.5 percentage points to meet the sector’s elevated and rising inflation expectations.

The world is once again having to acclimatize to higher rates. US 10-year yields this week rose above 5% for the first time since 2007. But they may need to climb even further to clear the market as other sectors continue reduce their Treasury exposure, leaving households as the only net buyer.

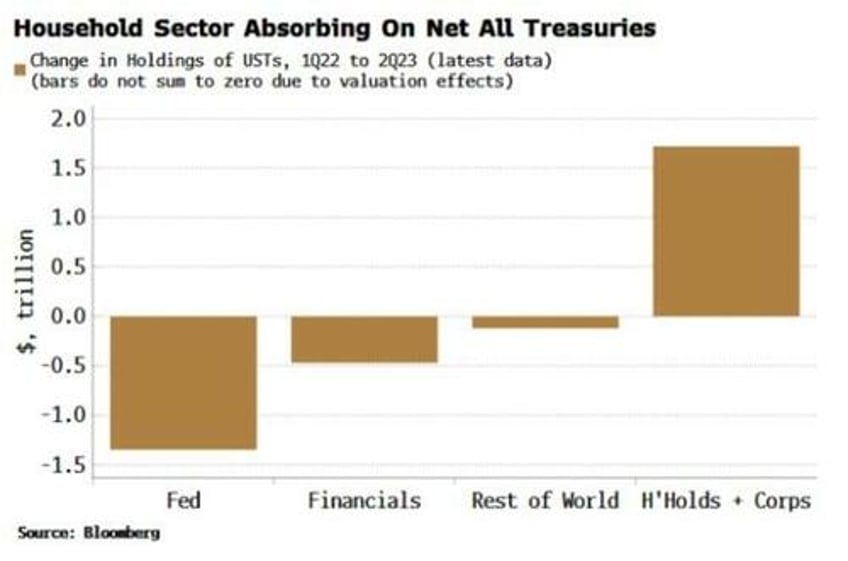

For every seller, there must be a buyer. The Federal Reserve, financial firms and the rest of the world have all been net sellers of USTs since last year, leaving the household sector (including the corporate sector it de facto owns) to pick up the slack.

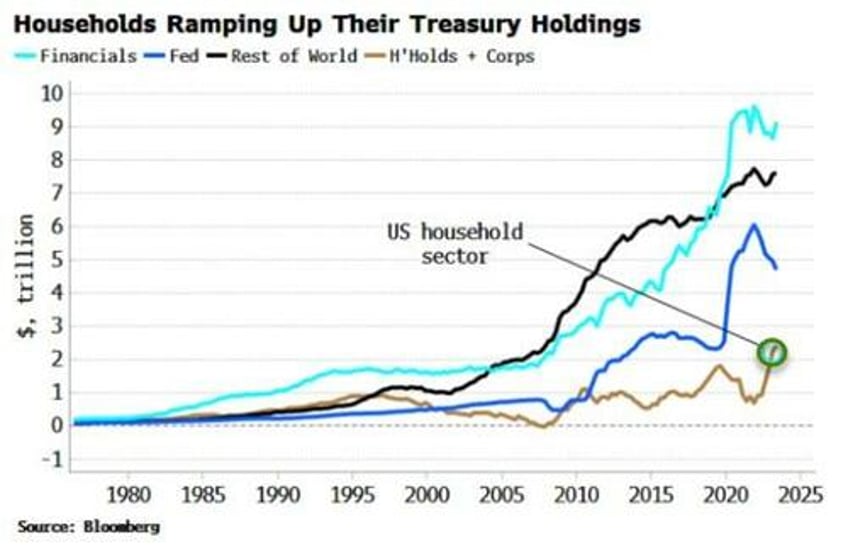

Households have historically been the smallest holder of Treasuries, but in the space of less than two years they have increased their holdings by $1.7 trillion, taking them to a new high of $2.4 trillion. The way things are going, households may end up owning a lot more yet – but they’re likely to demand a greater yield than currently on offer to compensate for the risks.

In the years just before the pandemic, all sectors other than households were happily hoovering up Treasuries. But now they’re reducing their duration exposure in the face of the fastest Fed rate-hiking cycle yet seen.

Most obviously, the Fed is no longer a buyer, with its UST holdings falling $1.3 trillion from their peak as part of its quantitative-tightening program.

There is little sign the Fed won’t carry on with the current pace of QT, especially with reserves still more than $1 trillion above most estimates of their lowest comfortable level.

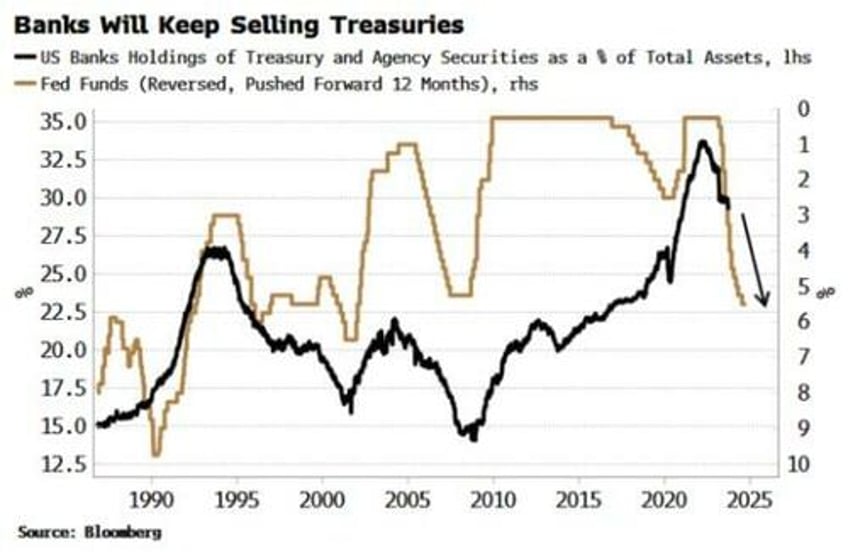

US banks, too, have been reducing their exposure to duration through Treasuries. Before the Fed started hiking, Treasury holdings of banks had reached all-time highs. But banks typically row back on their UST exposure when rates rise. As the chart below shows, they are likely to continue to shed Treasuries well into next year.

US Treasuries have also lost their allure to overseas buyers. High short-term rates and an inverted yield curve have made US yields after FX hedging costs very unattractive to erstwhile large buyers like Japan. Further, non-Western-aligned countries are becoming more reluctant to hold US government debt in case they face Russia’s fate and see their FX reserves frozen.

But where there is the greatest potential for large-scale Treasury divestment is in the non-bank financial sector. Asset managers, mutual funds and other multi-asset investors have no essential need for Treasuries. But they became increasingly attractive to them as portfolio and recession hedges as long as their correlation to stocks was negative.

However, stocks and bonds are reverting to co-moving together now that the inflation genie is out of the bottle. Investors not bound by liability-matching needs may question owning Treasuries if they are no longer enhancing risk-adjusted returns or are unlikely to work as a recession hedge.

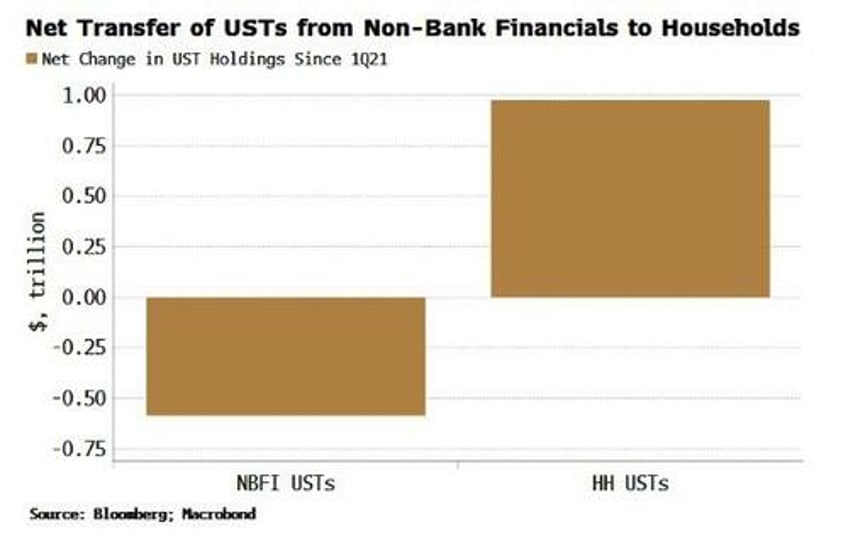

Since 2021, non-bank financials’ UST holdings have dropped by almost $600 billion, accounting for over 60% of the net rise in the household sector’s holdings. The positive stock-bond correlation hints households may end up taking on a lot more of unwanted Treasury debt currently held in 60/40-like portfolios.

Recent rises in yields have been driven by term premium – a sign that the market is becoming increasingly wary of supply and therefore inflation risks. But cushioning the blow has been the RRP facility. The Treasury has been skewing its issuance toward bills this year, and as their yield is higher than the RRP (and as we gradually get closer to the point where the Fed will eventually cut rates), money market funds (MMFs) have been transferring funds from the RRP to bills.

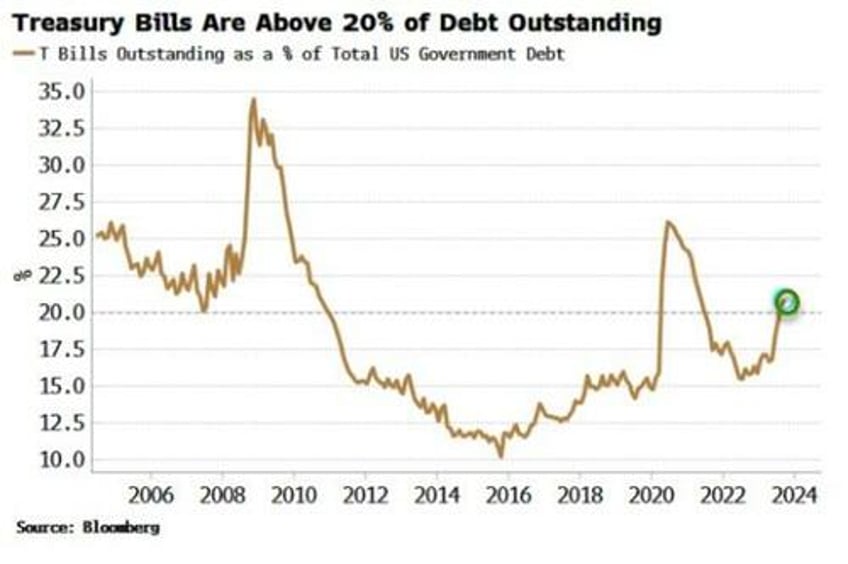

But bills are now above 20% of total Federal debt outstanding, around the upper bound of where the Treasury has aimed to cap bill issuance in the past. Future auctions will increasingly skew toward bonds and away from bills.

As that trend continues, the RRP will provide less of a cushion as MMFs are unable to invest directly in longer-term debt (even if they can indirectly through repo).

The Fed, banks, multi-asset investors and overseas buyers are unlikely to provide much support, leaving the household sector as the marginal buyer and therefore the setter of the clearing price.

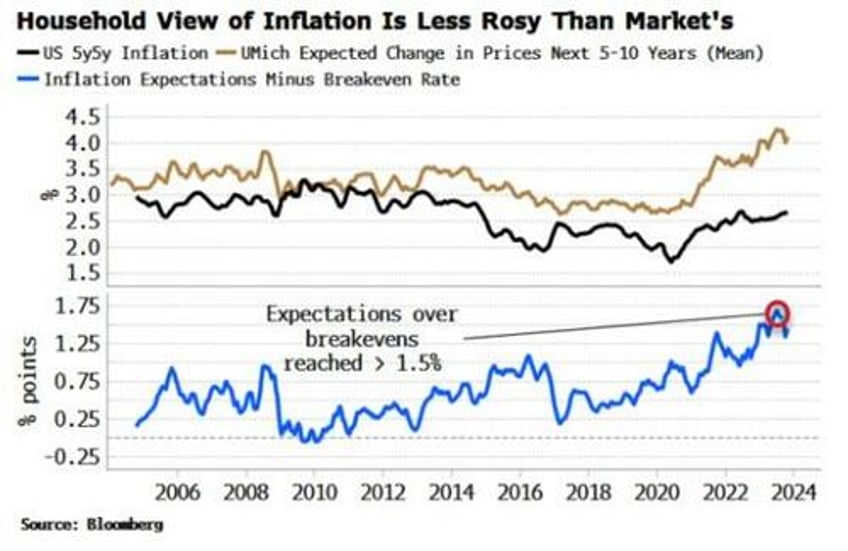

But what is that price? That largely depends on the outlook for inflation. The market has been remarkably sanguine in its inflation outlook this cycle, despite the highest consumer price growth seen for several decades. The 5y5y forward inflation breakeven rate has risen from around 2% in 2019 to 2.75%.

The household sector is much less optimistic. Shorter-term inflation expectations, based off the University of Michigan survey, are almost back to their pre-pandemic levels, but longer-term expectations – pivotal for bond yields – remain elevated.

As the chart below shows, the gap between households’ and the market’s inflation expectations has widened to at least 15-year highs, with a recent peak of more than 1.5 percentage points.

Heightened inflation has been with us more than two years now, and households will increasingly be growing wise to money illusion.

Regardless of whether they have as nuanced an understanding as the market of inflation-duration risks, they are likely to demand more yield compensation than the market is currently offering, with a rough-and-ready estimate - given by the excess of the household sector’s anticipated long-term inflation above breakevens - of 1-1.5 percentage points over time, or perhaps even more if bond and inflation volatility remain high.

It’s not about who’s ultimately right on inflation, but who’s left - and at the moment that’s US households.