China held a funeral and cremation ceremony for former premier Li Keqiang on Thursday, making an effort to hustle him off the national stage quickly and quietly while mourners quoted his words as veiled criticism of increasingly unpopular dictator Xi Jinping.

Li reportedly died from a sudden heart attack last Friday at the age of 68. A surprisingly large number of Xi’s subjects have speculated that Li was killed by the regime because he was becoming a “lightning rod for public frustration,” as Oxford research associate George Magnus put it to Radio Free Asia (RFA) on Thursday.

Li died amid a massive rolling purge of Communist Party officials who were either disloyal to Xi or embarrassing. The purge appears to have intensified as Chinese subjects grow more unhappy with a cratering economy, soaring youth unemployment, and poor government responses to various crises.

Xi will never have to face an election or an honest public opinion poll, and straightforward criticism of his autocratic government is policed by a vast A.I.-enhanced censorship operation, so disgruntled Chinese must find subtle ways to express their displeasure.

Li, a onetime rival to Xi for top leadership with a somewhat exaggerated reputation as a “reformer,” represents the road not taken for many Chinese unhappy with the current dictatorship.

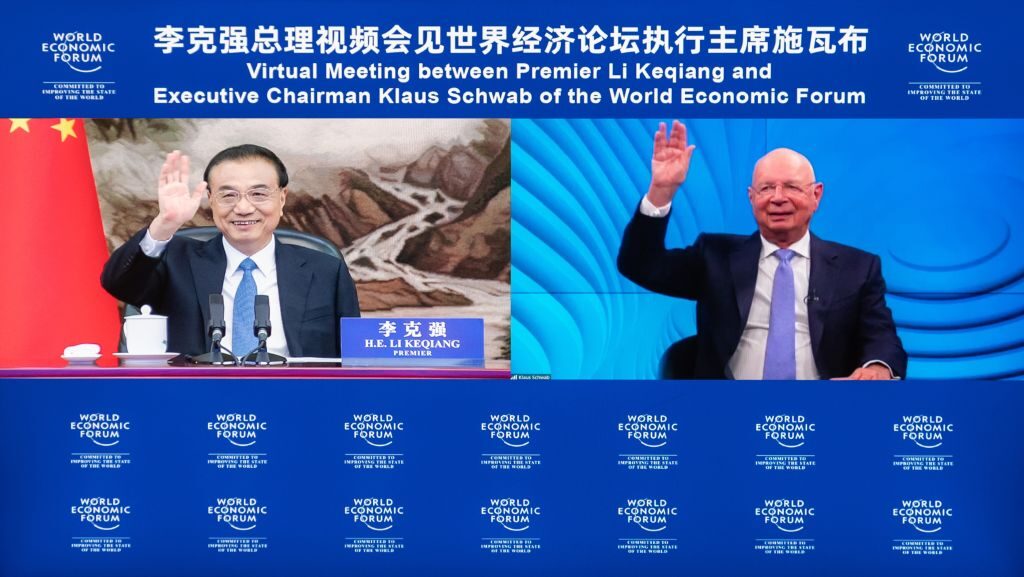

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang meets with Klaus Schwab, executive chairman of the World Economic Forum WEF, via video link at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, capital of China, July 19, 2022. (Zhai Jianlan/Xinhua via Getty Images)

“No one can know how he would have managed the last decade differently from Xi, but his reputation and credibility in death may resonate nevertheless for people at a time of growing economic and social stress,” said Magnus, who expected the regime to “manage Li’s funeral to ensure it passes swiftly and without public significance.”

RFA noted that Li received a funeral in accordance with “protocol” established after the death of former premier Li Peng in 2019, but he was not given a public memorial service, probably because the regime knows “public memorials for state premiers can transition into protests against the established leadership.”

It was just such a memorial-turned-protest after the death of a former premier in 1989 that eventually grew into the Tiananmen Square protest, which the Chinese Communist Party addressed by turning it into the Tiananmen Square massacre. In that case, the late premier was named Hu Yaobang and he was forced out of power two years before he died, becoming a martyr for liberalization in the eyes of pro-democracy students.

Mourners pay their respects in front of the childhood home of former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang in Hefei, Anhui province, China, on Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2023. China cremated the body of Li on Thursday and lowered national flags to half-staff, after his sudden death sparked an outpouring of emotion for a popular reformer. (Andrea Verdelli/Bloomberg via Getty)

Li also had fans who regarded him as the “people’s premier,” a sobriquet bestowed in deliberate contrast to the aloof and callous Xi. While Xi was trumpeting China’s rising power and bullying its neighbors, Li was talking about China’s working poor. Li was seen as much less ideologically rigid than Xi, whose policies have often sacrificed general prosperity to reinforce Communist Party control.

China affairs director Dexter Roberts of the University of Montana told RFA that many Chinese believe “Li, who came from a humble background unlike princeling Xi, cared about the many less well-off people of China.”

Roberts noted that public tributes to Li look suspiciously like backhanded criticism of Xi, whose rise to power kneecapped the reform and liberalization trend that began in the late 1980s. Another China scholar named Perry Link said Xi was not doing a very good job of pretending to be “grief-stricken” at Li’s passing, and it has been noticed by the public.

Reuters noted “tens of thousands of people” leaving comments on Weibo, China’s heavily censored social media platform, which replaced its “like” button with a chrysanthemum flower of mourning for the occasion. Li became the top trending topic on Weibo with some 430 million views.

Chinese President Xi Jinping (L) talks with Premier Li Keqiang (R) during the opening of the first session of the 14th National People’s Congress at The Great Hall of People on March 5, 2023 in Beijing, China. (Lintao Zhang/Getty Images)

One such mourner praised Li for making “a great contribution to people’s lives, to the improvement of living standards,” and because he “always rushed to the front line” during the Wuhan coronavirus pandemic. Such comments drew a rather stinging contrast with Xi, who disappeared during the pandemic and brought China to the brink of an uprising by imposing brutal lockdowns that turned cities into horror shows.

The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) found some of Li’s more memorable quotes going viral on Chinese social media as a way for mourners to “subtly rebuke top leader Xi Jinping for seemingly breaching Li’s promise” of liberalization.

One popular saying of Li’s was “The Yangtze and Yellow rivers won’t flow backwards,” which was his way of saying that China’s opening to the outside world could not be reversed. For many Chinese who are normally afraid to say it out loud, Xi has been paddling upstream on those rivers of reform.

Another sharp example of backhanded criticism was Peking University praising alumnus Li as an “intelligent and diligent reader of books” who left the world with “one less scholar” when he passed. Xi, by contrast, has dubious academic credentials and acts as though the only book everyone should be reading is the one he wrote.

Exiled Chinese author Hao Qun told the WSJ that Li has become an avatar for disgruntled and dispossessed Chinese, a “mirror image” of those left behind during Xi’s march to power and wealth for his favored elites. These people believe they have been “humiliated” and sidelined by Xi, just as Li was.

“When they mourn Li Keqiang, they are also mourning themselves,” said Hao.

China’s titanic censorship machine has already swung into action to tamp down public appreciation for Li, suppressing encomiums that look too much like veiled shots at Xi.

The WSJ noted that social media messages have been scrubbed, especially those mentioning a song called “A Pity It Wasn’t You” that has been interpreted as an insult to Xi. The Chinese Foreign Ministry scrubbed condolences from American officials from its readout of Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Washington last week.