Did the U.S. government really try to confiscate Americans' gold?

The short answer is... well, there isn't a short answer. It's a complicated subject with more nuance than most people give it.

Yes, President Franklin D. Roosevelt did try to take most of the gold out of the public's hands. But the scheme didn't go quite as well as many people claim.

Still, some gold dealers use the confiscation story to try to scare you into only buying collectible coins because there was an exception in Roosevelt’s order for “gold coins having a recognized special value to collectors of rare and unusual coins.” They’ll say, “The government could come to take your Gold Eagles as they did in 1933, but not these collectible coins we’re selling.” Of course, these collectible coins come with higher premiums and bigger profits for the dealer.

You might call it a confiscation con because the reality is there wasn’t “confiscation” in the strict sense of the word.

So what actually happened?

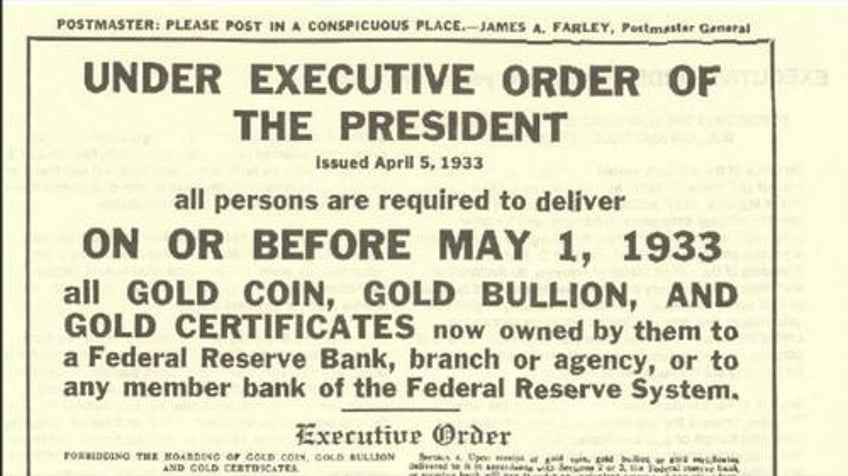

On April 5, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102. He justified the move based on the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, as amended by the Emergency Banking Act in March 1933.

At the time, the United States was in the grip of the Great Depression. A lot of people were redeeming paper dollars for physical gold because they were losing faith in the paper currency. This caused significant problems for the federal government because the dollar was tethered to gold, and thus, the printing of it was at least somewhat limited.

During a Fireside Chat a month before issuing the EO, Roosevelt claimed gold “hoarding during the past week has become an exceedingly unfashionable pastime,” and he said that it was undermining the banking system. The use of the word “hoarding” was almost certainly intentional because of its negative connotations.

This carried forward to EO6102. Stopping hoarding was the public rationale for the order, but it went far beyond merely taking large amounts of gold from “hoarders.” By creating an expansive definition of “hoarding,” the EO was designed to take virtually all gold coins and bars out of private hands and transfer them to the government.

“The term ‘hoarding’ means the withdrawal and withholding of gold coin, gold bullion, or gold certificates from the recognized and customary channels of trade. The term 'person' means any individual, partnership, association or corporation.”

In short, anyone who wanted to hold their gold as a form of savings was considered to be “hoarding.”

Under the order, private citizens, partnerships, associations, and corporations were required to turn in virtually all their gold.

The order allowed people to keep up to $100 in gold coins, along with gold “as may be required for legitimate and customary use in industry, profession or art within a reasonable time,” and “rare” coins.

It read, in part: “Deliver on or before May 1, 1933, to a Federal Reserve Bank or a branch or agency thereof or to any member bank of the Federal Reserve System all gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates now owned by them or coming into their ownership on or before April 28, 1933.”

In return, the Federal Reserve Bank would give individuals an equivalent amount in “any other form of coin or currency coined or issued under the laws of the United States” at the rate of $20.67 per ounce.

Once the government got the gold at that price, it did what governments do – it changed the price-fixing to its advantage, raising the price to $35 and devaluing the paper money people received in exchange for their gold.

Violators of the law were subject to up to a $10,000 fine and/or 10 years in prison.

Like so often happens today, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act before the majority of members had even read the bill. It expanded The Trading With Enemy Act of 1917 (TWEA), a WWI statute still on the books today, prohibiting trade with enemies of the United States.

One provision in the 1917 law empowered the president to regulate or prohibit “under such rules and regulations as he may prescribe … any transactions in foreign exchange, export or earmarkings of gold or silver coin or bullion or currency … by any person within the United States.”

On March 6, 1933, President Roosevelt declared a national emergency under § 5(b) of the TWEA, authorizing him to declare a bank holiday to prevent the hoarding of gold. The President invoked this authority even though the section explicitly limited presidential power to wartime.

Congress then retroactively amended the section to allow the president to take action “during time of war or during any other period of national emergency declared by the president” when it passed the Emergency Banking Act three days later.

Provisions in the Emergency Banking Act gave the secretary of the Treasury the power to require all individuals and corporations to hand over all their gold coin, gold bullion, or gold certificates if in his judgment “such action is necessary to protect the currency system of the United States.”

This served as the legal justification for EO6102.

What Was the Motive Behind Roosevelt's Gold Confiscation Scheme?

Despite the window dressing and propaganda, Rosevelt’s order wasn’t a benevolent move to protect America from greedy gold hoarders. In truth, the government needed the gold.

With the dollar tied to gold, the Federal Reserve could not significantly increase the money supply during the Great Depression. It couldn’t simply fire up the printing press as it can today. The Federal Reserve Act required the central bank to hold enough gold to back at least 40 percent of the notes in circulation.

But the central bank was low on gold and up against the limit.

Since monetary stimulus – an increase in the supply of money – is the Keynesian response to an economic downturn, Roosevelt was between a rock and a hard place. He wanted the Fed to increase the money supply and support government spending but was limited by this partial gold standard.

By transferring gold from the public to the Federal Reserve, the central bank boosted its reserve holdings, allowing it to print more money than it was previously able to.

Gold confiscation was the second step in Roosevelt’s aggressive plan to weaken the gold standard.

EO6102 followed on the heels of Executive Order 6073, which Roosevelt issued just weeks prior, prohibiting banks from paying out or exporting gold.

A little over a year after the enactment of EO6102, the United States effectively went off the gold standard when Congress passed the Gold Reserve Act of 1934. In effect, this law transformed gold from a currency to a commodity.

One of the most significant provisions in the law erased the right of creditors to demand payment in gold. In practice, this forced debtors to make payments in whatever the government declared was legal tender. Gold couldn’t even be used as the basis for determining how much paper money was owed.

As noted above, when people were ordered to turn in their gold they were given a rate of $20.67 per ounce, but the government wasn’t done.

The war on sound money continued in 1934 when President Roosevelt issued a proclamation raising the fixed price for gold to $35 per ounce. This effectively boosted the value of gold on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet by 69 percent.

By increasing its gold stores through the transfer of private gold to the Fed, and declaring a higher exchange rate, the Fed could circulate more paper money. In effect, the hoarding of gold by the government allowed it to inflate the money supply.

Was the Gold Confiscation Order Enforced?

The short answer is "barely."

EO6102 is often referred to as a gold confiscation order, and in principle, it was. Roosevelt effectively nationalized gold. But the word “confiscation” conjures up images of police breaking down doors to forcibly take people’s gold.

That’s not what happened.

The Federal Reserve collected plenty of gold, but only because many Americans turned it in voluntarily as an act of obedience. Some likely did so because they trusted the government, others out of a sense of patriotism, and some probably turned their gold in out of fear.

But generally speaking, federal agents did not search for private holdings or seize gold. People took their gold and gold certificates to the bank and received the promised compensation.

As Tom Woods noted in The Great Gold Robbery of 1933, “The paper currency they were receiving in exchange for the gold had always been redeemable in gold in the past, so few saw anything amiss in this coerced transaction, and most trusted the government’s assurances that this was somehow necessary in order to combat the Depression.”

The total amount of gold turned in to the Fed remains unclear because the central bank isn’t required to disclose detailed accounting. However, in their book A Monetary History of the United States, economists Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz estimated the amount was relatively small and that most people simply ignored the order.

According to their calculations, Americans turned in about 20 to 25 percent of gold held in private hands at the time. In other words, a large percentage of people simply ignored the order.

Friedman and Schwartz came to this conclusion when they found something wonky in the official government data. The amount of gold the government said it held (in dollar terms) before the confiscation order was abnormally low.

“If the estimates of gold lost and gold exported without record are added to the gold coin returned to the Treasury since 1934, we are still far short of accounting for even half of the $287 million. We therefore concluded that in Jan. 1934 the bulk of the $287 million was retained illegally in private hands.”

In effect, the Federal Reserve cooked the books to make it look like more gold was turned in than was. Economist David Henderson explains it this way:

“The government thought that x gold existed in, say, 1930. Then, when people were supposed to turn their gold over by law in 1934, the government calculated that there was only 0.8x. Rather than concluding that people were withholding 0.2x of gold, the government went back and said, ‘Oops, we overestimated the amount of gold in 1930. It must have been falling due to factors y and z.’"

Looking at gold coin mintage versus gold meltdown figures confirms the 20 to 25 percent turn-in rate, along with official gold reserve data.

This goes to show that, like most other federal actions, the gold confiscation actually depended primarily on the voluntary cooperation of the people.

That’s not to say the government didn’t try to enforce the orders.

Frederick Barber Campbell was the first person to find himself in federal crosshairs. He had over 5,000 ounces of gold on deposit at Chase National Bank. When the bank refused his request to withdraw the gold after Roosevelt issued EO6102, Campbell sued the bank, bringing himself to the attention of federal prosecutors.

A judge overturned the prosecution because the president signed EO6102 instead of the Treasury secretary as required under the Banking Act of 1933. But the court upheld the federal government’s authority to confiscate gold and still seized Campbell’s holdings.

Campbell was the only person prosecuted under EO6102

After the judge nullified the federal enforcement authority in EO6102, Roosevelt signed EO6260 to empower the Treasurer to make rules relating to gold confiscation, to allow for licensed individuals to hold gold, and to authorize federal prosecution under the direction of the Treasurer.

“Whoever willfully violates any provision of this Executive Order or of any license, order, rule, or regulation issued or prescribed hereunder, shall, upon conviction, be fined not more than $10,000, or, if a natural person, may be imprisoned for not more than 10 years, or both; and any officer, director, or agent of any corporation who knowingly participates in such violation may be punished by a like fine, imprisonment, or both.”

The Gold Reserve Act of 1934 also included provisions beefing up the power to prosecute individuals illegally holding gold.

“Any gold withheld, acquired, transported, melted or treated, imported, exported, or earmarked or held in custody, in violation of this Act or of any regulations issued hereunder, or licenses issued pursuant thereto, shall be forfeited to the United States, and may be seized and condemned … And in addition, any person failing to comply with the provisions of this Act or of any such regulations or licenses, shall be subject to a penalty equal to twice the value of the gold in respect of which such failure occurred.”

Following the pattern Campbell established, most of the prosecutions happened after people got caught in sting actions trying to illegally sell gold, or otherwise did things that brought attention to their “illegal” gold.

For instance, the government prosecuted a San Francisco diamond and jewelry merchant after he tried to sell thirteen $20 gold coins without a license. Gus Farber got busted when the buyer tipped off the Secret Service. Faber and his father, along with 12 other people, got caught up in the subsequent sting operation. Federal agents confiscated $24,000 in gold.

Other prosecutions followed a similar pattern. It’s unclear exactly how many people were prosecuted under the various orders and laws, but there weren’t a lot. Most criminal actions involved individuals trying to sell gold. There are no recorded cases of individuals being prosecuted merely because they had gold in their homes.

By and large, Roosevelt’s gold confiscation largely relied on voluntary compliance. The federal government made no effort to hunt down people who quietly ignored the order.

A lack of personnel and resources to enforce federal actions is an ongoing problem for the federal government. As Roger Sherman noted in 1787, “All acts of the Congress not warranted by the constitution would be void. Nor could they be enforced contrary to the sense of a majority of the States.”

The same holds true today. When people and the states refuse to cooperate or submit, the federal government has a hard time doing anything.

This article was adapted from a report published by the Tenth Amendment Center.