The printer in the corner of Martin Lukongo’s print shop in Goma, a city in DR Congo’s troubled east, vibrates as it churns out an order for 400 copies of a book.

For more than 30 years, this part of the vast central African country has been known for the conflict that now surrounds the city, rather than for any literary output.

Some consider reading a luxury, even a futile activity, especially in a nation ranked as one of the world’s poorest.

But a collective of artists and activists has set out to encourage young people to develop a love of books by overcoming the hurdles to produce them locally.

“Writers prefer to print in Europe, as they think they can’t obtain this quality here,” Lukongo said.

A photographer by trade, he manages to overcome power cuts and a shortage of high-quality paper by obtaining it from neighbouring countries to print around 60 copies — including books, novels and essays — a day.

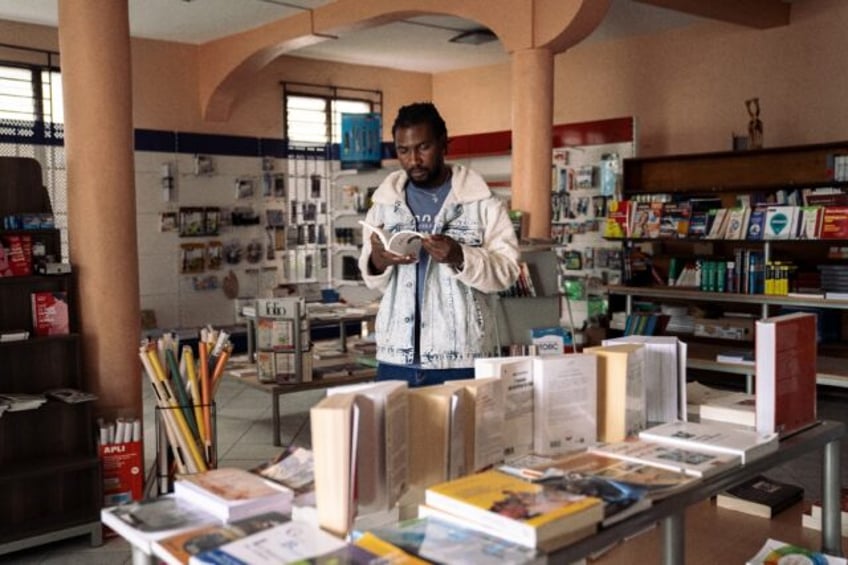

Buyers nevertheless are few and far between in a city of scant bookshops where the prices of works imported from Europe usually range from $20 to $60 — equivalent to several days’ wages for many people in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

“Very few young people can afford these books, unlike other items such as beer which is on special offer every weekend,” Depaul Bakulu, one of the founders of Mlimani publishing house, said.

The collective set up an online collection to fund the creation of a local publishing house.

Viewing a lack of access to books as a “danger for the youth”, Mlimani offers works at prices ranging from $5 to $10.

A year and a half on from its launch, the Mlimani catalogue boasts a dozen published authors.

Among them are French psychoanalyst and social philosopher Frantz Fanon, Congolese gynaecologist and Nobel Peace laureate Denis Mukwege, and novelists, researchers and essayists, the majority from the DRC.

What they have in common is “books that talk about the culture of young Congolese or have a direct relationship with their lives,” Bakulu said.

“They say Congolese don’t read, but we realised that the problems were much more related to supply,” he added.

‘Revolt’ and look to future

Mlimani-published works are distributed in the majority of DRC’s main cities by a partner network.

Its members visit schools and cultural centres in search of potential readers, whom they entice with group reading sessions.

On a recent morning, a dozen or so people gathered in downtown Goma to discuss a new Mlimani publication — “L’Histoire Generale du Congo” (“A General History of Congo”) by Congolese historian Isidore Ndaywel E Nziem.

“The idea is above all to sit down around a table and discuss subjects that concern us,” Victor Ngizwe, a student running the workshop, said.

“It allows us to distribute content without forcing people to buy the book.”

Participants are mostly young men who describe themselves as committed and seeking intellectual tools to “revolt and work out what to do with their future”, one of them, law student Steven Sikubwabo said.

With two volunteers raising some of the high points in the nation’s history, an animated group discussion is soon under way.

It’s a far cry from the usual available fare of history mostly written by foreign authors in books primarily published and sold abroad.

It’s one that also rarely gets passed on to new generations.

“At school, teachers drum European history into us. We don’t get to talk about African antiquity, we don’t talk about the Middle Ages in Africa,” poet-raconteur Gautier Barhebwa said.

“In every civilisation, the past serves as a mirror to the present. We need to construct folklore that can unite us,” another participant Victor Ngizwe said.

Other local publishers have sprung up in the wake of Mlimani.

“It’s encouraging for young readers — but also for those who are ready to take up writing,” Lukongo said.

“You don’t have to send your books elsewhere in order to sell them here,” he added.