About 10,000 trainee doctors in South Korea entered their second month of a nationwide strike in late March, forcing hospitals into “emergency mode” and shutting down critical sectors, including emergency wards, Korean news agencies confirmed Wednesday and Thursday.

The trainee doctors launched their strike in late February to protest a plan announced by conservative President Yoon Suk-yeol to increase the number of slots for students at medical schools, which he insisted was necessary to address long-term shortages in the healthcare system. South Korea currently has one of the lowest ratios of doctors to people in the developed world and has been struggling in particular with shortages of critical sectors such as pediatrics and emergency room doctors. Yoon announced that the government would begin increasing the number of medical students by 2,000 in 2025 and gradually increase the number every year, ideally concluding with the creation of 10,000 new slots by 2035.

“Increasing the medical school admissions quota by 2,000 is the bare minimum necessary measure to ensure the state can fulfill its constitutional mandate,” President Yoon asserted in February.

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol speaks during a pre-recorded interview with KBS television at the presidential office in Seoul, South Korea, on February 4, 2024. (South Korea Presidential Office via AP)

Polls at the time showed that as many as 75 percent of Koreans supported Yoon’s plan. Yet in response to the proposal, the Korean Medical Association (KMA) led calls for a strike by trainee doctors who complained that increasing the number of doctors in the country would create undue competition in the field and hurt their salaries. Thousands of doctors resigned, while some simply stopped showing up to work. Reports began surfacing of hospitals rapidly canceling non-essential surgeries and nightmarish anecdotes of ambulances being turned away at hospitals. In one such incident in late February, South Korean news networks reported the death of an unnamed woman in her 80s who experienced a medical emergency and was taken away by an ambulance. The ambulance was rejected at seven hospitals and she reportedly died in the eighth, which finally accepted her.

As of Thursday, the South Korean Yonhap News Agency reported that over 90 percent of the 13,000 trainee doctors in South Korea are still on strike.

“With the junior doctors’ walkout, understaffed hospitals had no choice but to cancel or reduce their medical appointments and operations, which are their primary revenue sources,” the Korea JoongAng Daily detailed on Thursday. The newspaper named five hospitals in the Seoul area that were forced to cut appointments, close wards, and otherwise limit services. One of the largest, Seoul National University Hospital, reportedly closed ten of 60 wards, including its “short-stay ward at the emergency room” and some of its cancer treatment wards.

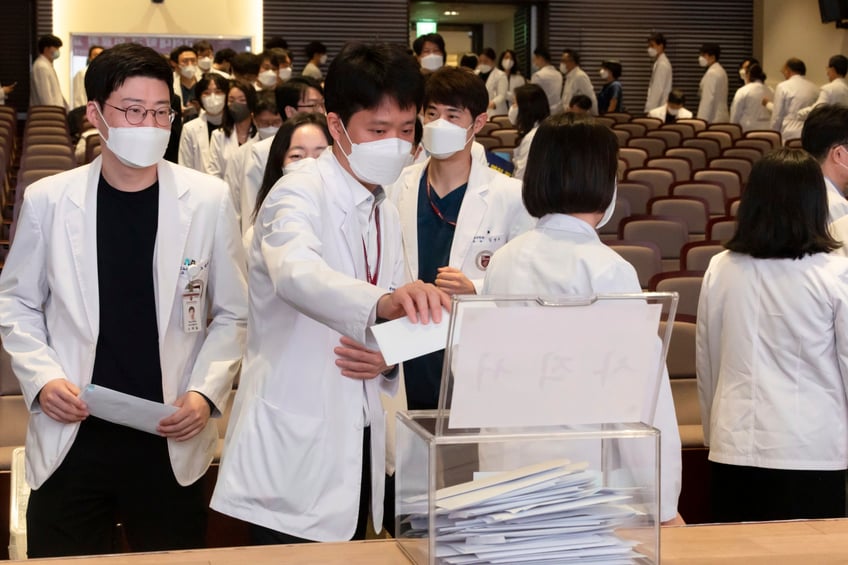

Medical professors queue to submit their resignations during a meeting at Korea University in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, March 25, 2024. (Yoon Dong-jin/Yonhap via AP)

“Asan Medical Center — accruing a daily debt of over a billion won ($7.4 million) due to a decreased number of patients — shut down nine wards out of its 56,” the newspaper reported. “The hospital entered a phase of emergency business management on March 15.”

Some of the hospitals in question are attempting to limit the rapidly rising debt by asking staffers to take unpaid time off, as the hospitals do not have enough patients to justify maintaining its usual capacity of health workers.

Yonhap, reporting on the same five major Seoul hospitals, tallied the total debt the institutions are facing as increasing by over $740,000 a day.

“We cannot even forecast when the situation will end as trainee doctors have not reported to work and professors have tendered resignations,” an anonymous hospital official told Yonhap. “Remaining workers have also been thinly stretched.”

Members of the Korea Medical Association stage a rally against the government’s medical policy near the presidential office in Seoul, South Korea, on February 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

The government has attempted to respond to the crisis by threatening administrative and criminal consequences for the doctors. In late February, the federal government filed criminal charges against five senior members of the KMA for allegedly organizing and facilitating the strike. Days later, police raided two of the largest KMA offices in the country, an apparent attempt to dissuade strikes from failing to show up at work. Strikers persisted, however, and authorities threatened to suspend their medical licenses, potentially ending their careers.

As the deadline to suspend the thousands of trainees on strike arrived, however, the Yoon administration suddenly paused plans to take their licenses away. Authorities referred to the pause as a “tentative deferral,” threatening to finally execute the threat eventually if doctors persisted in striking, but said the deferral was in light of attempts to hold talks with medical leaders. Seoul also announced some new measures to entice health workers to talk with the government, including capping working hours at 80 per week for junior doctors and reportedly handing out reward bonuses for doctors studying obstetrics – an underserviced specialty in the nation with the world’s lowest birth rate – and emergency medicine.

The KMA elected a new president this week in the aftermath of the raids in early March. Lim Hyun-taek used his victory speech to threaten an “all-out strike” in which experienced doctors joined the trainees in walking out and demanding Yoon apologize to all doctors. Lim reportedly demanded an apology as a precursor to talks, then urged Yoon to personally sit down and negotiate with the doctors.