The Q3 quarter-end repo spike could point to reserve scarcity, but more likely indicates that dealers are reaching capacity limits. Dealers are forced to comply with balance sheet constraints and Basel III leverage ratios (like the SLR) purposed to prevent their bank holding company from taking on too much risk (too much leverage). But the monsoon of Treasury issuance which dealers are forced to absorb, finance and hold on their balance sheet means that even when things seem placid, their fragility only grows.

There’s one straightforward solution to increasing a dealer’s ability to provide liquidity and make markets: exempting Treasuries from said regulations. This would make banks a limitless marginal buyer of Treasuries and explain the SEC’s confidence in throttling the current marginal buyer – hedge funds. An exemption would be a “crossing the Rubicon” moment for the US Treasury and the first step towards an endgame.

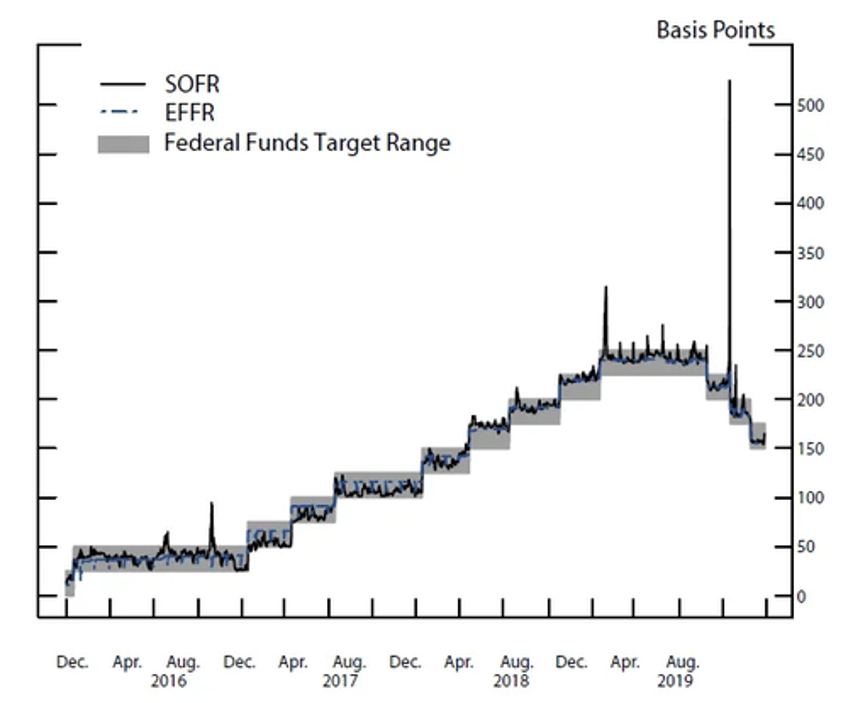

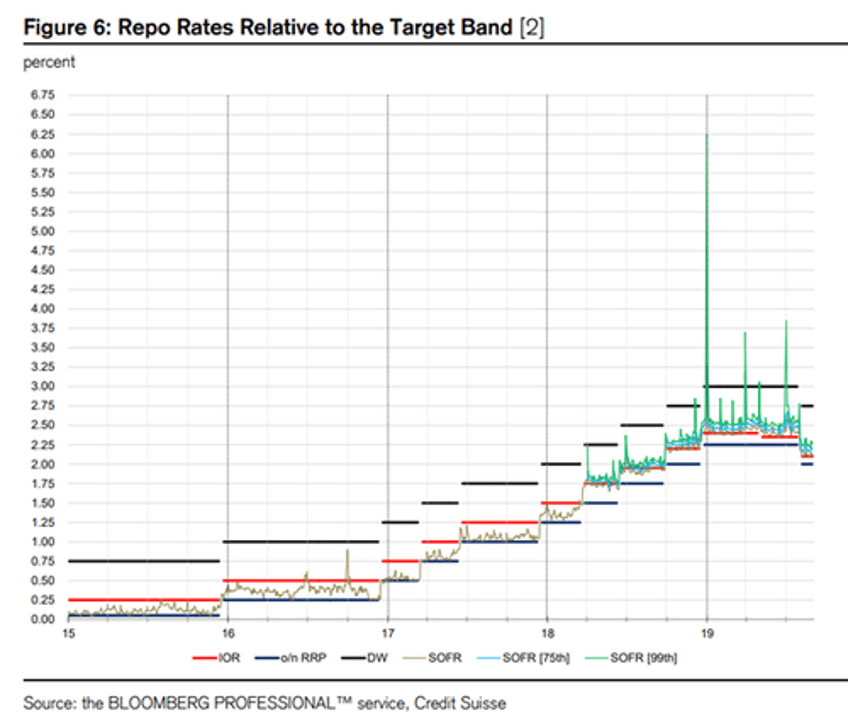

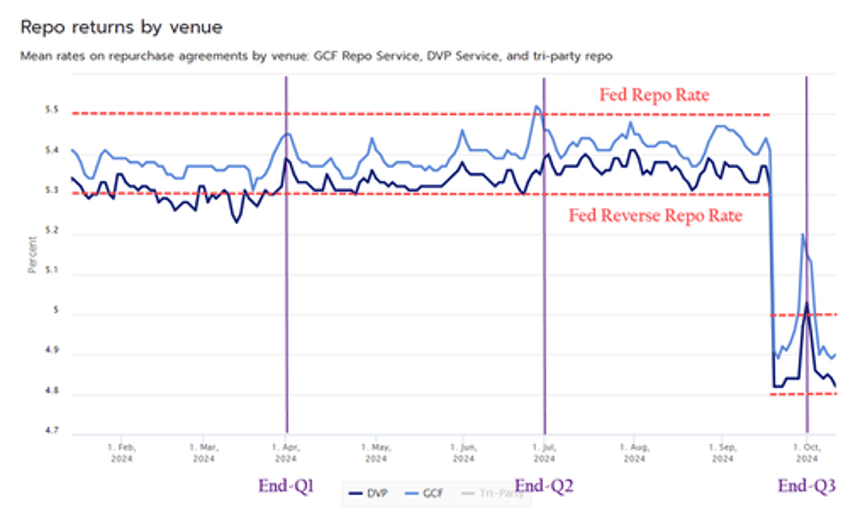

Only a couple of days ago, zerohedge cited repo guru Mark Cabana’s warning on the large reserve drain into Q3 quarter-end, which sent Treasury repo rates spiking above even what was offered at the Fed’s repo facility. The facility, designed by Zoltan Pozsar, was created to prevent another September 2019 episode, when repo rates spiked far above the Fed’s target range:

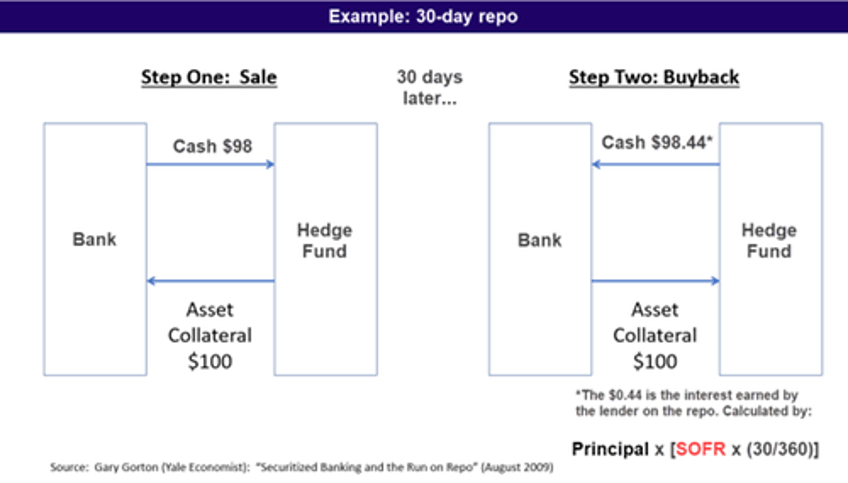

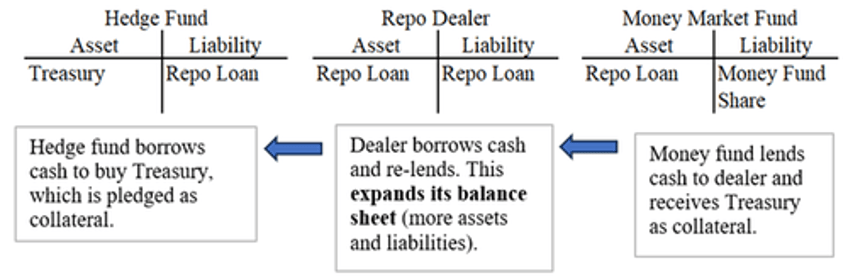

Recall that a classic repo trade is borrowing cash secured by Treasury collateral: a dealer, for example, can borrow $100 from a money market fund to finance a security purchase (or whatever it may be) by pledging $101 worth of Treasuries. The extra $1 is called the haircut. The “pawn” analogy is perfectly accurate: you sell an item to a pawn shop for some amount of cash and agree to repurchase (“repo”) it back at some time in the future. If you can’t repurchase it, the shop will keep the item you sold. Thus, the transaction is secured by collateral, and here, that collateral is almost always Treasuries.

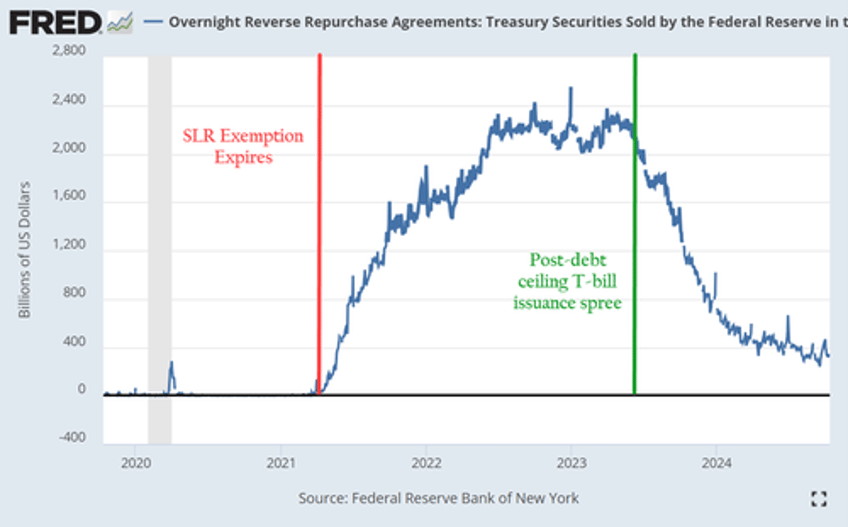

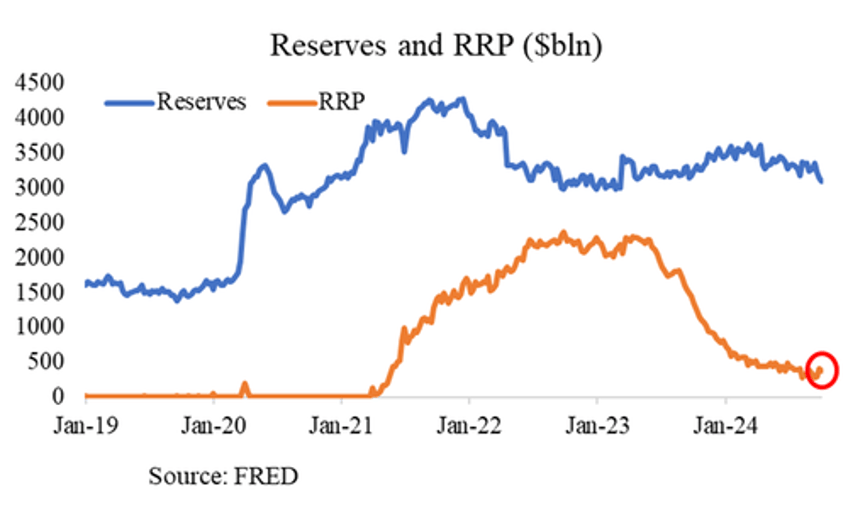

A reverse repo trade is the opposite side: lending cash and accepting Treasury collateral to secure the trade. Back in early 2023, when banks were saddled with "too much" cash leftover from 2020 sloshing around the financial system, they would lend it to the Fed in an overnight reverse repo. The Fed’s reverse repo facility has been drained some ~$2 trillion since, as the cash found its way into higher-yielding Treasury bills.

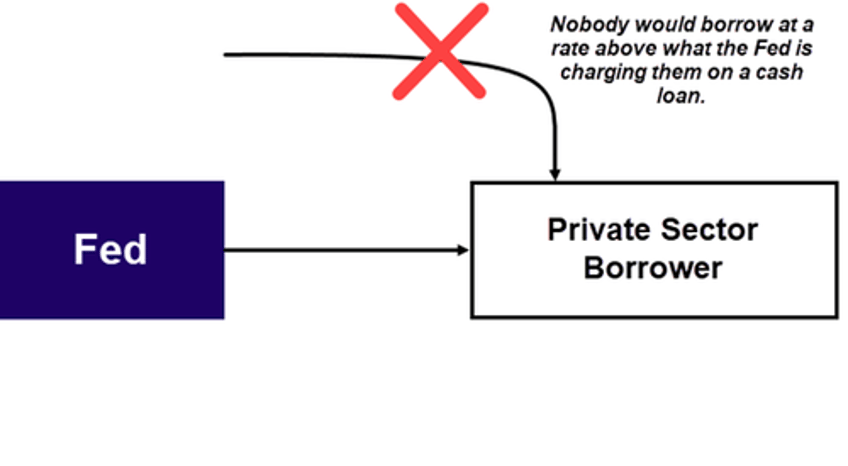

If private sector borrowers (such as pensions, hedge funds, or asset managers) need cash, they will first tend to borrow in private repo. As a last resort, they can (since 2021) borrow cash from the Fed’s repo facility. Think of repo borrowing as a service (more demand = more expensive) and realize that it’s increased demand for repo borrowing that puts upward pressure on repo rates. If $100 needs to be financed but only $90 is available to be lent, the borrowers will compete with one another by offering to pay higher and higher rates.

The Fed’s repo backstop, the repo rate, should act as a ceiling on rates:

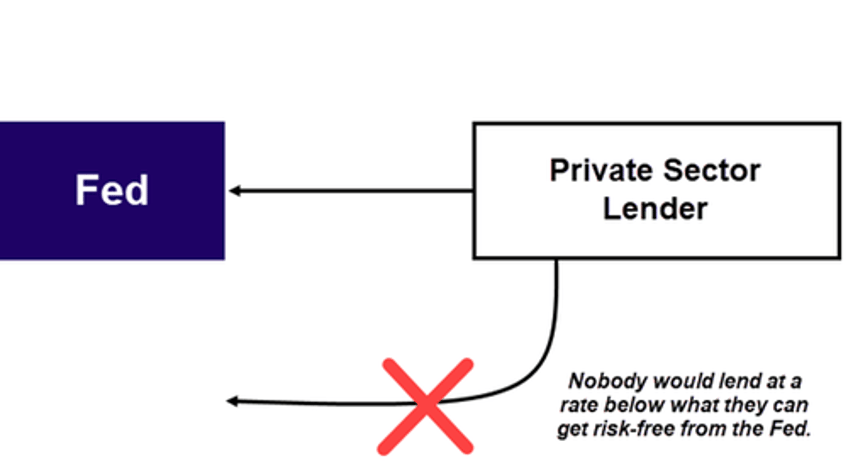

On the other hand, if private sector lenders have cash to deploy, they will first seek to lend in private reverse repo venues (i.e., they will just lend it to private sector cash borrowers). As a last resort, they can lend cash to the Fed. Again, think of repo lending as a service (more cash available = more competitive rates) and realize that it’s an increased supply of repo lending that puts downward pressure on repo rates. If there is $100 available to be lent but only $90 needed to be financed, the lenders will compete with one another by offering to accept lower and lower rates.

The Fed’s reverse repo (RRP) backstop, the reverse repo rate, should act as a floor on rates:

This is the best framework to think about “rate spikes” or “funding squeezes.” As Cabana even notes, funding markets are determined by three key fundamentals: cash, collateral, & dealer balance sheet capacity.

Too much cash relative to collateral (a.k.a. a collateral shortage)? Funding rates go lower. Too much collateral that needs to be financed relative to cash available to finance it (a.k.a. a cash shortage)? Funding rates go higher and can spike.

With that in mind, the “easy way” to see a funding rate spike (such as in repo) is to deduce that it signals a cash shortage. But this ignores Cabana’s third “key fundamental”: dealer balance sheet capacity. More on that in a moment.

With that review out of the way, it’s time to think about what quarter-end repo spikes mean. First, period-end spikes (especially year-end spikes) are well known, basically staples of the Basel III world as mostly European banks, who are net repo lenders, “window dress” their balance sheets come period-end by scaling back their repo lending.

But that still doesn’t answer the rate spike question because since 2021, the Fed lends cash at its repo facility, so why would repo rates spike above that offered by the Fed (5% as of today) if a cash borrower can pay less just by going to the Fed? We could even ask “what repo facility?” Because by the looks of it, we’re back to early 2019 and the Fed’s repo facility was hardly a rates ceiling and more like an imagination.

Did it misfire at the first test? Is the list of counterparties not big enough? Is there a cash shortage as reserves (cash used by banks) were allocated elsewhere?

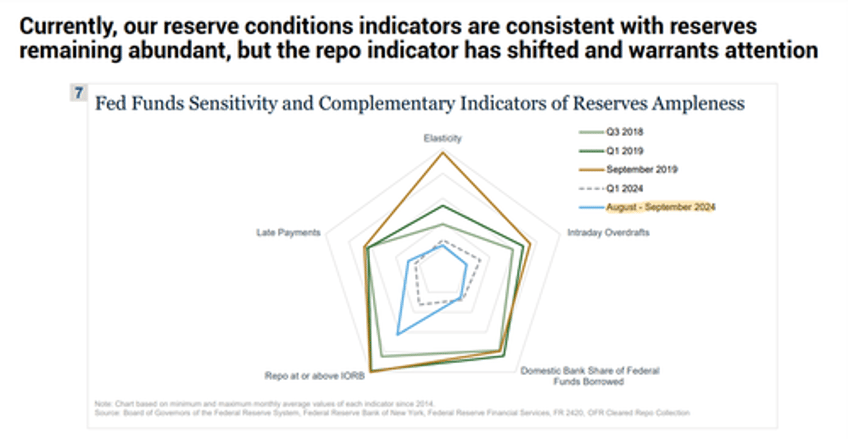

There are a couple of ways to think about this, the “easy way” is to look at signs of reserve scarcity. Remember, a cash shortage puts upward pressure on repo rates. That’s where the New York Fed looked last month. The indicator below can seem confusing to read, but the closer all five points on the pentagon are to the center, the more abundant reserves (cash) are; the further towards the outside, the scarcer they are. The blue line is the most recent, by comparison:

The takeaway is that, by all accounts, reserves (cash) remain abundant, so stress in the repo market must originate elsewhere. Oddly enough, they didn’t think of exploring the root cause, only admitting that it “warrants attention.” So, while repo rates spikes could signal reserve scarcity (a cash shortage), this time, it’s more likely something else, Cabana’s third “key fundamental”: dealers reaching balance sheet limits.

That’s a host of more serious issues: reserve scarcity is an easy fix – the Fed can just pause QT (which removes reserves from the banking system) or, if it must, restart QE (which adds reserves to the system). Dealers reaching balance sheet limits, however, is a structural problem that basically demands a crisis before it can be resolved. Getting Powell to announce that QT will end after 30 successful months due to funding stresses is one thing. After all, this is the same Powell who is slashing rates into inflation. But rewriting (not just “suspending”) and rethinking an entire regulatory framework such as Basel III is another, much more cumbersome process.

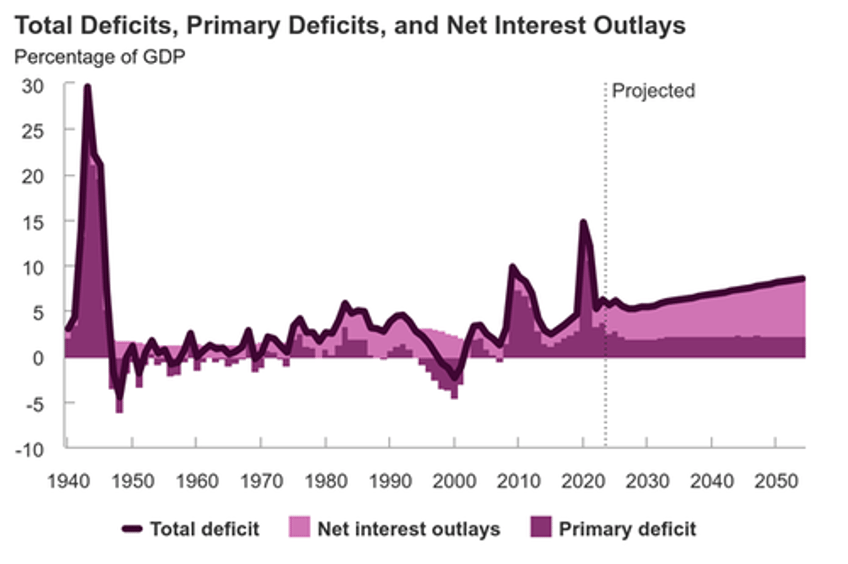

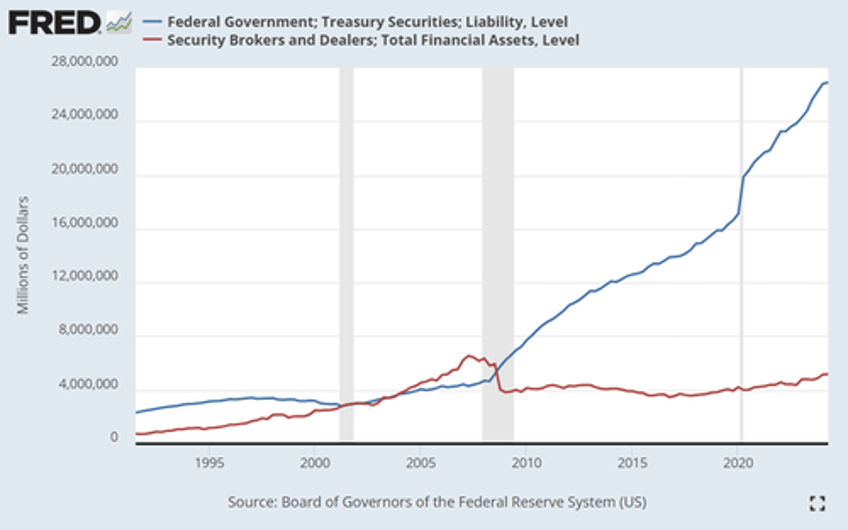

Since late August in my first article published onto zerohedge, I’ve been warning that another March 2020-like liquidity event in bonds is looming. The structural problems in the Treasury market have not improved since 2020 – to the contrary, they have only grown more fragile. It’s important to remember that these problems have nothing to do with a lack of demand for Treasury bonds. They were built into the post-GFC world where limiting risk taking became paramount, but have not caught up with the post-Covid world where financing forever deficits will be "paramount":

In subsequent articles I focused on this demand side of the problem: the cash-futures basis trade has been buying (read: providing liquidity for) Treasuries on the margin since late 2022. Several things can blow that trade up: a Treasury selloff, a credit event (such as a bank failure), or voluntary regulatory decisions ironically intended to protect it from eating itself.

But what if we get none of that? No violent Treasury selloff. No bank failures. What if even the SEC’s stranglehold fails to take it down? When all is said and done, it doesn’t matter, and that’s for two reasons. First, Treasury supply (borrowing) is unending, and dealers are obligated by law to make (buy from sellers and sell to buyers) Treasury markets. Treasury supply expanding to infinity means balance sheets must accommodate to infinity.

Second, since the Great Financial Crisis, banks are outfitted with an alphabet soup of regulations that limit how much “risk” they can take relative to how much cash they have on hand. Thus, their obligation to absorb Treasuries is constrained, and to do so they pull back from other activities like repo and FX swap lending.

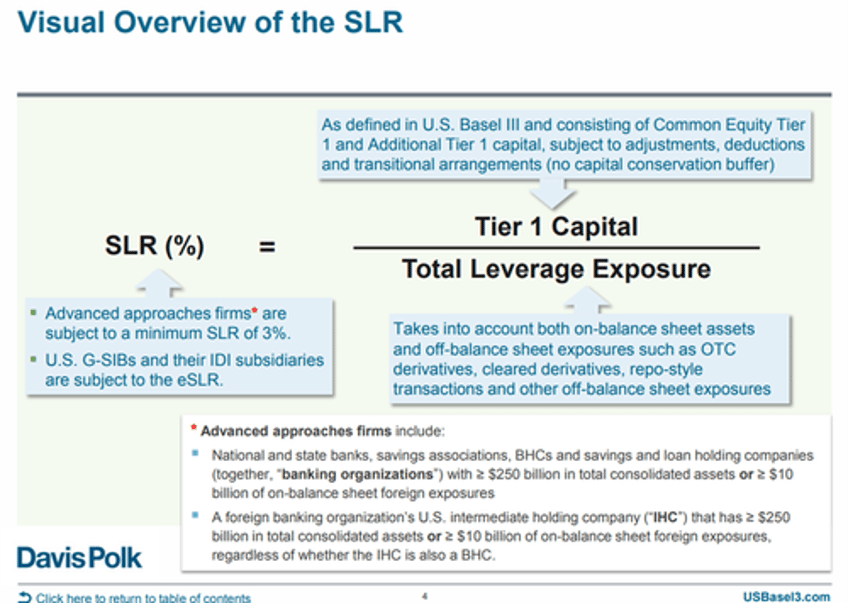

In other words, post-GFC, banks no longer have infinite space for Treasuries on their balance sheet. To comply with the most relevant Basel III regulation, the Supplementary Leverage Ratio for example, they must hold a certain amount of “prime” liquid capital against all assets (except bank reserves):

It’s the SLR that makes repo financing, which is large in volume but low on margin, unattractive. Recall that in a typical repo financing trade, a dealer borrows from a cash lender (such as a money market fund) and then relends the proceeds to a Treasury buyer (such as a hedge fund), earning a small spread in the process. The transaction is low risk and low margin, but high in regulatory costs because it significantly expands the banks’ balance sheet.

And that’s the last thing a bank can afford, especially at period end…

And there you have it – that is how pipes burst: even an “unclogged pipe” (solid demand for Treasuries from end investors) will give way to enough “water pressure” (enough Treasuries coming through) and implode at the even a tiny “pinhole leak” (a disturbance that spills over into Treasury volatility).

To follow the “pipe” analogy, the only solution is to expand the pipe’s capacity to intake water by making them bigger and wider.

During the peak of Covid in early April 2020, regulators exempted Treasuries from the SLR. Remember, the SLR mandates that all on-balance sheet bank assets (except for reserves) must be backed by a certain level of capital. Equipped with war-time balance sheet space (the exemption meant they had infinite space for Treasuries), banks could readily absorb and finance the tsunami of pandemic related borrowing.

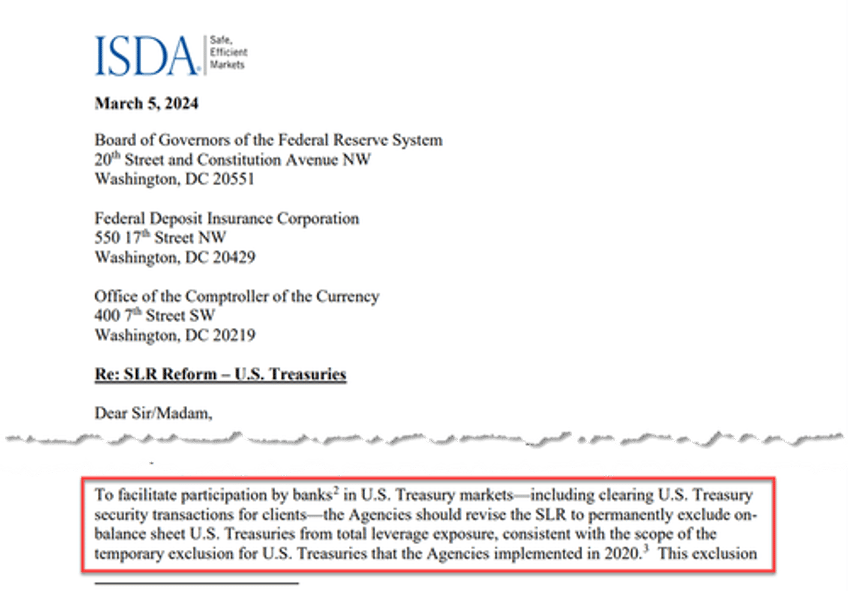

Following a comment made by Fed Governor Bowman from January, and seemingly out of the blue for anyone not thinking about how much of a problem this can be in the future, the IDSA formally recommended a permanent exemption a couple months later:

A dealer’s willingness to make markets depends in part on the "costs" of warehousing the Treasury. Leverage ratios like SLR significantly raise those costs by requiring bank affiliated dealers to hold capital in proportion to the size of their assets, even if the assets are risk-free. These costs disincentivize market making, even when it is critical to the Treasury market as is the case in repo.

Note that dealer asset holdings (which proxies for warehousing capacity) remain sharply below its pre-GFC peak, even as the Treasury market has obviously swelled. The growing mismatch between market size and warehousing capacity has contributed to a steady deterioration in market resilience – it’s far more fragile than in 2020; even the failure of a mismanaged regional bank shook the entire market to its core last year.

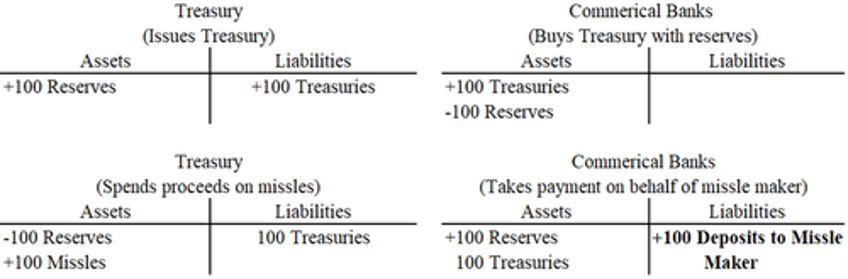

Bank purchases of Treasuries are functionally the same as QE, so a shift to a bank financed government, where banks can hold as many as they would like, would replicate it. In QE, the Fed buys a Treasury and leaves the non-bank sector with more deposits that can then be rebalanced into other assets, but a bank purchasing a Treasury would also increase the deposits of non-banks:

The difference is largely in the motivation behind Treasury purchases, where Fed purchases are intended to place downward pressure on Treasury yields and bank purchases would be due to regulatory encouragement. But the impact on asset prices, inflation expectations and yields may not be that different. It would also be a solution to financing future Treasury issuance without the heavy hand and poor optics of the Fed resorting to QE. It will, mechanically, be a permanent indirect QE program, and be the next, and biggest, step towards an endgame.

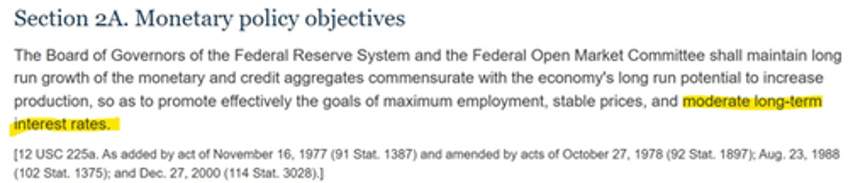

That’s because, for all we hear about the Fed’s “dual mandate” (stable prices and maximum unemployment), the Fed admits that this is not exactly honest and indeed that it has not a dual mandate but a triple mandate – maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates:

But looking at the Fed’s endgame, and how thinking about how or why they get involved if banks are limitless buyers, is best for another article.

What would this transition period look like? I’ve said before that when the Treasury market is looking for a marginal buyer, volatility ensues. If banks struggle to finance and hold Treasuries for hedge fund customers, that will qualify.

I truly do believe that it will be a March 2020 redux - a sharp asset selloff (Treasury selloff, equity selloff... the worst kind of risk parity) until the Fed steps in to announce a rule tweak, which signals the bottom and greenlights the “everything bubble rally” to continue. Albeit a little less dramatic than 2020, though, unless there is some other seismic event going on in the world (what a convenience coincidence that would be!).

Now the moment you've (maybe) all been waiting for: when? What we’re asking is “when will balance sheets be overwhelmed to the point where dealers fail to make Treasury markets?”

It depends on a lot of things. If officials are looking at signs of reserve scarcities everywhere except repo rates (which it sounds like they're doing, even admitting that repo pressure “warrants attention”), we’ll see a situation where reserves remain “ample”, but Treasury repo is in disarray until the leverage ratios are reformed.

That would basically be the mother of all mixed signals.

Maybe the Fed follows what the BoE did in 2022: “shoot first and asks questions later” with a brief return to (real) QE. Maybe they save themselves the trouble of it and make the regulatory changes. But the important point is that, without the capacity for banks' dealers to repo lend, the rest of the Treasury market begins to flounder.

As for timing, it's again difficult to pinpoint. But we can start by asking if the Fed stops QT, what could make reserves become scarce?

Next year, debt ceiling drama is set to return. That means the Treasury General Account (TGA, Treasury’s cash balance at the Fed) will begin draining from January 1st, only seeing quarterly upswings due to tax remittances, until the debt ceiling is suspended once again.

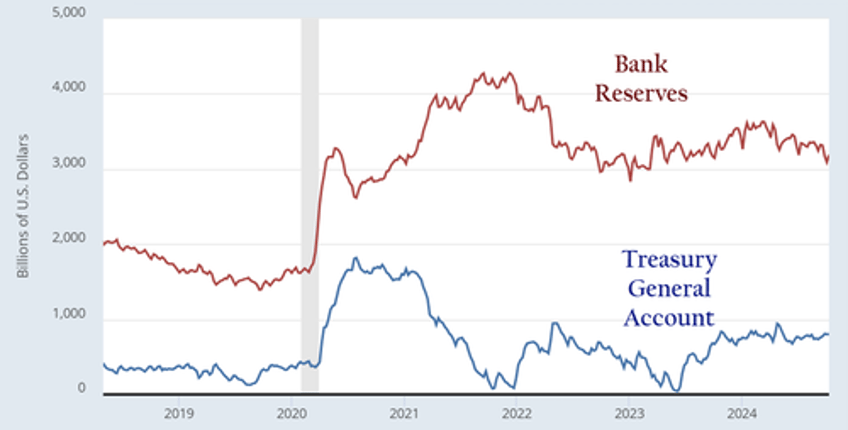

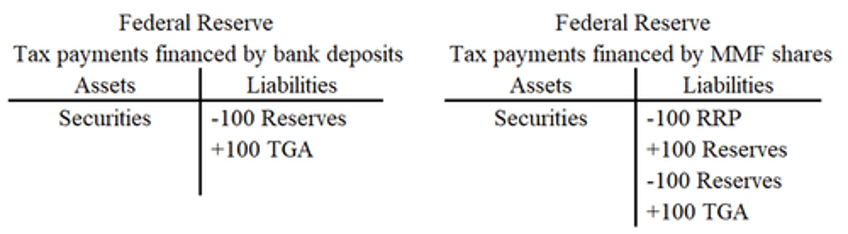

The TGA is a liability on the Fed’s balance sheet. In that sense, it is no different from bank reserves (which are also the Fed’s liability). Reserves move back and forth between the banking system and the TGA in a liability swap: a reserve drain refunds the TGA; a TGA drain adds reserves back into the banking system. Reserve balance liabilities cannot leave the Fed’s balance sheet unless it is also rolling assets off its balance sheet (doing QT).

The other liability is the cash balance parked at the Fed’s reverse repo facility but, since it’s now nearly exhausted, it won’t be as relevant as it was in June 2023 when there was over $2 trillion.

The next looming debt ceiling fiasco will be a tailwind for bank reserves, because just like in early 2023, the Treasury will resort to ‘extraordinary measures’ and spend down its $800 billion TGA balance.

“Without QT, reserves don't leave the Fed's balance sheet. A TGA drain adds reserves.”

There is one date in 2025 that I can’t stop thinking about – the April 15 Tax Day. And this is where reserve scarcity and cash shortages make an appearance because, although QT will probably be over by that point, a reserve drain is still a reserve drain. Tax payments are ultimately financed either from cash held in banks (i.e., drawn from bank reserves) or money market funds who lend to the Fed’s reverse repo facility:

In April 2022, when individual income taxes for 2021 were collected, the TGA (Treasury’s cash balance at the Fed) rose by about $400 billion largely thanks to the whopping equity rally in 2021. With the S&P within teasing distance of 6000, and business activity no longer restricted by pandemic era regulations (as was the case during 2021), at least $500 billion or more in April 2025 tax receipts would be a cautious estimate. That's all coming from the banking system.

Officials like to point to there still being “substantial remaining balances at the (Fed’s RRP) facility,” and so the Treasury’s 2023 playbook – where the TGA was funded by bills that saw MMFs rotate out of the Fed’s RRP and into Treasuries – is still in play for 2025.

But as the Fed’s portfolio manager Roberto Perli noted three weeks ago, the RRP balances likely haven’t rolled out of the Fed’s facility because it takes time – which can be years – for MMFs (cash lenders) to establish relationships with dealers (cash borrowers). Hence why “despite rates on alternative instruments (including repo rates) often higher than the (Fed RRP) rate”, balances at the Fed's RRP remain stubborn. So, the reverse repo facility is itself, for all intents and purposes, tapped out.

With the RRP tapped out, the 2023 playbook won’t refill the TGA. Reserve drain. And April taxes – a lot of them – are financed by banks. Reserve drain.

At the end of the day, if dealers have infinite balance sheet space for Treasuries, this is QE. It will look like QE, behave like QE and solve the problems QE is designed to address, but nobody in the official sector will call it that. That is the next step, and the disconnect between repo rates and other reserve scarcity indicators, combined with the SEC's Hail Mary to sabotage the current hedge fund buyer, make it all the more obvious.

The repo spike means it's probably something to expect sooner rather than later.