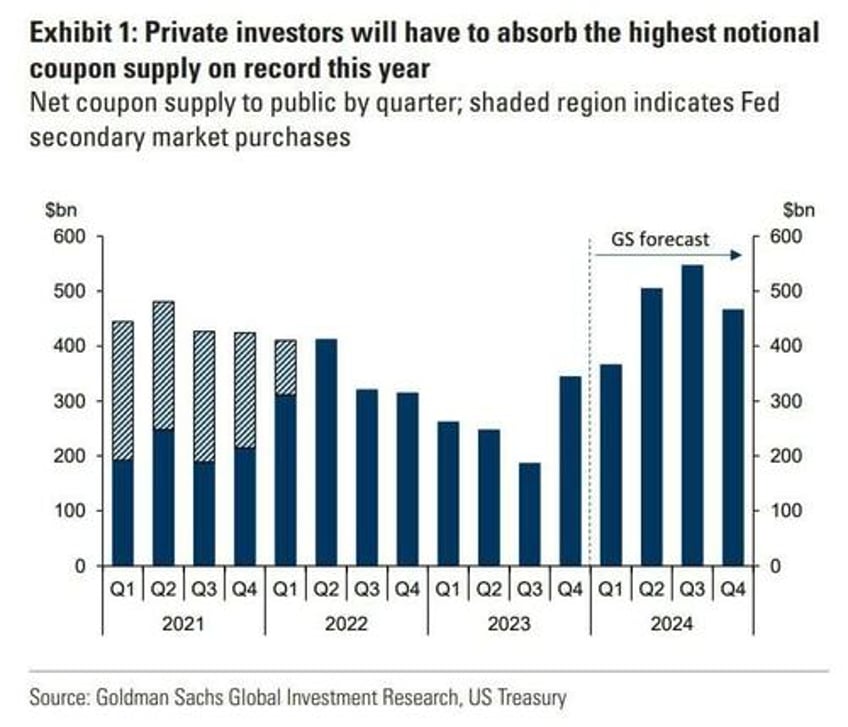

Late last year, Yellen had the task of finding some marginal bid for the tsunami of longer-dated US debt (coupons which, in Basel 3 terms, are the most cumbersome for dealers to hold on their balance sheet) slated to be issued over the next few quarters.

The consensus was that – basically – yields would have to go higher, and perhaps much higher, to attract new cash investors.

Volatility in yields was the most logical thing to expect.

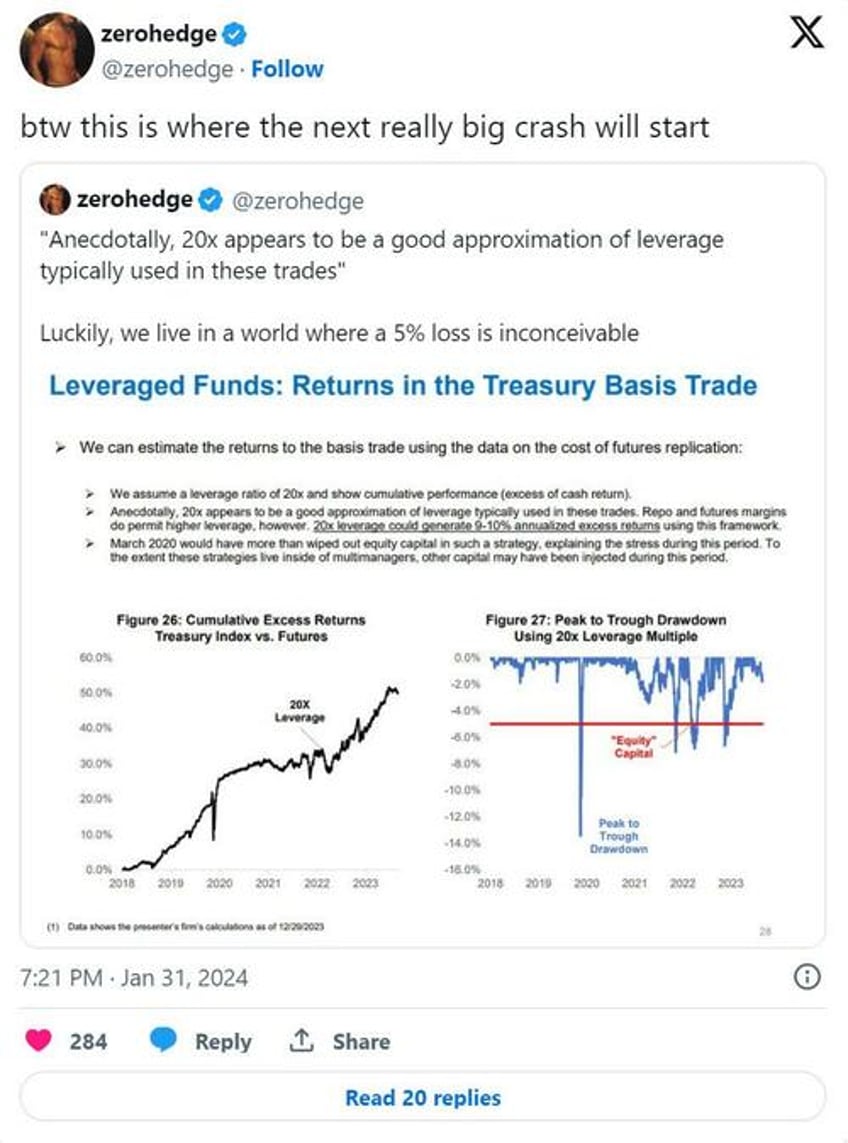

For some context, American RV hedge funds have been the marginal buyer for Treasuries as part of a cash-futures basis trade, but there are binding constraints that would limit their firepower.

Crucial to a basis trade are dealers willing to hold the security on their balance sheet, which incurs regulatory costs at a time when they are already chock full. The costs are then transferred from the dealer, who is acting more like a custodian, to his investor - costs such as wider bid-ask spreads, higher repo rates and larger swap spreads that inevitably disincentivize the trade. Regulators would have to suspend leverage ratios (exactly what they did in 2020 and what Bowman set the stage for back in January) to remove these inherent costs, and perhaps cut rates to reduce the "dealer premium" (less negative swap spreads).

Of course, when all else fails, the Fed could step in as the end investor of last resort and announce “temporary” liquidity support like the BoE did in 2022 (and not unlike the Fed itself did in September 2019).

And although year-to-date we’ve seen our fair share of tailing auctions up and down the yield curve, suggesting all this issuance hasn’t been digested without incident, it overall went more smoothly than anticipated as banking liquidity remained “ample” and yields did not have to rise much to find cash buyers.

So, in hindsight, Yellen did get her wish: someone bought it up. But where did that demand come from and, more importantly, why does it even matter?

The first answer - who bought it - is, by and large, overseas investors.

Some recent data – from the Fed and from the Treasury – tell that the marginal bid came almost exclusively from foreign non-official investors – which means foreign banks, foreign pensions, foreign insurance funds, and other bodies, but namely foreign hedge funds as part of the highly-leveraged, infamous basis trade: buy the cash Treasury, short the corresponding Treasury futures, and - so long as volatility doesn’t cause the spread to explode in the meantime - net the difference when it's time to deliver the security on the futures contract.

It’s arbitrage and like most cases of arbitrage it’s highly leveraged (the hedge fund buys a Treasury, posts the Treasury in a repo trade as collateral and simultaneously uses the proceeds of the repo loan to finance that original purchase, putting up only a fraction of its own capital) and not risk-free.

The trade is certainly a “picking up pennies in front of a steamroller”-type deal, but getting into the nitty gritty is for another time.

The second answer - why does it matter - is because foreign buyers are vulnerable to foreign exchange risks should local currencies appreciate against an investment currency (see: the Yen carry trade that blew up on Yen strength earlier this month. It's really the exact same dynamic). This is an added dimension that U.S-based investors aren't liable to. Normally, this practice wouldn’t be an issue at all as foreign non-official investors can easily hedge out FX risk using a FX swap.

An FX hedged investment is essentially borrowing short-dated money: finance the trade in overnight rates to earn, in the case of Treasuries, the longer-dated coupon. While there’s no way of telling just how much foreign Treasury investment is hedged or not, it's not profitable for foreign investors to FX hedge their holdings while the yield curve is inverted (again, financing lower-yielding interest income with higher overnight rates results in negative carry), suggesting that the mass of it is "swimming naked."

And, since the foreign investors are largely "non-official" (as opposed to "official" central banks and sovereign pensions), they will be motivated by returns in their local currency.

Think about an example to visualize how this setup can deteriorate:

Say you are a Canadian pension fund willing to buying $100 in Treasury bonds, with the USD/CAD exchange rate at 1.40. This outright purchase (minus some transaction fees) would cost you $140 CAD. The Treasury bond may pay a coupon of 4.5%, split into two payments of $2.25 each twice a year, totaling $4.50 USD annually.

Now, when the dollar weakens (as happens in a rate cutting cycle, or a trade war), sending the USD/CAD exchange rate down to 1.30 for example, the value of the $100 USD bond would decrease to $130 CAD, resulting in a $10 CAD loss on the principal. This loss would outweigh the $4.50 annual coupon payment (which is actually even less now when converted back to CAD), leading to, all else being equal, a negative carry in Canadian dollar terms!

So, here you are: a Canadian investment manager who, so long as you own the unhedged bond as the dollar weakens, must enjoy watching his clients' money burn. Canada is but a single example - a huge buyer in FY2023 (curve has been inverted since November 2022), but the recent TIC data points to Europe providing the overwhelming marginal bid for the all-important U.S debt.

The FX risks to Treasuries are inherently that the dollar weaken significantly against it's G7 peers, i.e. EUR/USD and GBP/USD up, USD/CAD and USD/JPY down, etc. Since FX hedging costs are higher than the interest income so long as the yield curve is inverted, it does not make sense to hedge these investments in a FX swap (as it would "lock in" a loss on the investment).

If the best case scenario for unhedged foreign buyers is for the dollar to strengthen and to collect a coupon worth more in their local currency, then the worst case is for the dollar to weaken and leave the investor stuck earning a coupon worth less in their local currency. More likely than eating the loss, the ~$1t in foreign investment (total foreign demand for long-term Treasuries while the curve's been inverted) are more likely to sell - sending yields higher, which cheapens the Treasuries, inducing more selling until the vicious cycle ends in a panic firesale.

Less about the direction of yields, but more about dealers widening bid-ask spreads as their balance sheet becomes overwhelmed. Yes, yields would spike, but think about the volatility in March 2020, which did see a week-long spike in yields that was eclipsed by tumult under the hood...

... until the Fed stepped in, not with rate cuts or a new lending facility, but with QE (the real stuff).

And while some proposed structural changes can reduce the Treasury market's reliance on dealers or increase their trading capacity, at the end of the day there must be an end investor willing to hold the sold securities in exchange for cash. Dealers are only willing to do so because they can easily finance the purchases in the repo market.

If there were enough end investors in March 2020, then the dealers would have just sold the securities and there would not have been any liquidity issues. But there were almost no end investors, dealer warehousing capacity was maxed out, and the Fed swooped in to buy it all.

Similar to 2020, these funding stresses will likely pull away capital and hence balance sheet from equity long/short strategies which could spill over into a broader equity selloff... during a Treasury selloff.

The difference between now and 2020 is that lowering the overnight rate (hello rate cuts!) could only further deteriorate the dollar's exchange rate. FX traders know that interest rate differentials are the dominant force driving foreign exchange - rate cuts would exacerbate the negative carry held by those foreign investors, giving them even more reason to puke the trade onto some foreign dealer's balance sheet, who struggles to get rid of it but at a steep discount, etc.

And this line from Goldman: "There is a plausible risk that labor demand will prove to be a bit too soft. In that scenario, the FOMC would likely respond by cutting more quickly." The state of labor market demand may not come to light until several months after the election, by which point, the Fed will be in true-to-form catch-up mode.

The path to a weaker dollar (and Treasury dysfunction) now lies in the U.S labor market - that is, unless Europe and the rest of the G7 were to cut much deeper, which really is to say, unless they land much harder...