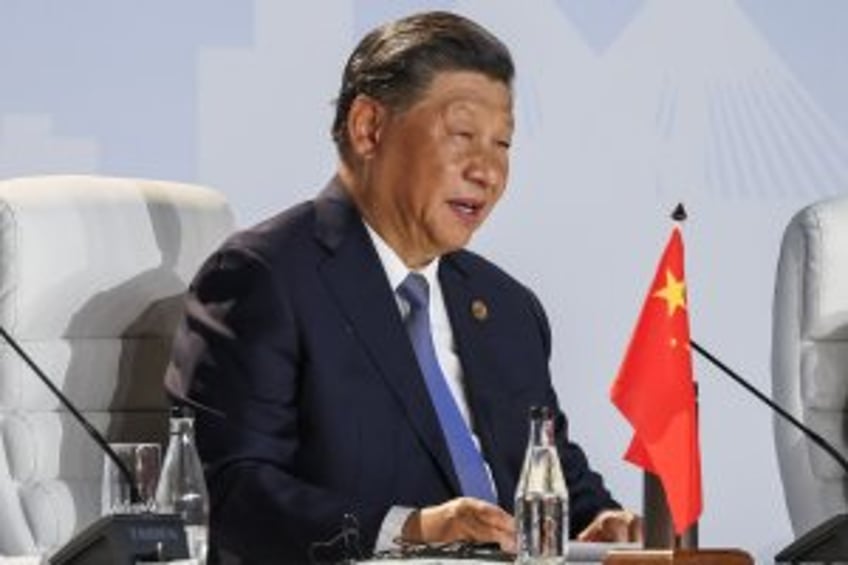

Dec. 17 (UPI) — On New Year’s Day, Chinese president Xi Jinping and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un jointly designated 2024 as the “China-DPRK Friendship Year” to mark the 75th anniversary of the two countries’ diplomatic relations. Despite this declaration, China-North Korea relations have significantly cooled this year. Kim’s growing ties with Russia represent a deliberate effort to reduce North Korea’s dependency on China, a strategy that aligns with his broader ambitions to modernize the country’s missile and weapons systems. This foreign policy shift is rooted not only in pragmatic national interests but also in personal motivations, including Kim’s complicated relationship with Xi.

Kim and Xi first met in March 2018, a remarkable delay of nearly six years after Xi became the head of state of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). According to insiders, Xi’s discomfort with Kim began early in his tenure. Shortly after becoming Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary in November 2012, Xi advised against North Korea’s third nuclear test in February 2013. When Kim went ahead with the test, Xi was deeply dissatisfied. This tension became glaringly apparent in 2014 when Xi chose to visit South Korea — North Korea’s adversary — before ever meeting Kim, a move that openly signaled his discontent.

Though the two leaders eventually held their first meeting in 2018, primarily to mend ties amid growing U.S.-led sanctions on North Korea, their relationship never fully warmed. The recent 2024 Russia-North Korea Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership has only deepened the rift, bringing China-North Korea relations back to a frosty state.

In late 2023, there were indicators that China would reinvest in its ties with North Korea. A flurry of Chinese diplomatic activity ensued following the summit between Vladimir Putin and Kim in Russia’s Far East during which Putin indicated willingness to provide North Korea technical support for its satellite program.

Ultimately, the only high-level exchange of the Friendship Year occurred in April 2024 when Zhao Leji, the Chairman of the PRC’s National People’s Congress, traveled to Pyongyang to meet with his North Korean counterpart Choe Ryong Hae, Chairman of the Standing Committee of the Supreme People’s Assembly. The meeting between Zhao and Choe reportedly initiated discussions of a loan agreement in which China would provide North Korea raw materials and food in exchange for priority access to minerals and investments in natural resource development projects, but such an agreement has failed to materialize.

For decades, China has pressured North Korea to emulate its path of economic reform, offering substantial aid to keep the regime afloat. However, this support has never been sufficient to address North Korea’s systemic shortcomings. Unlike China, where a party-state governs, North Korea’s hereditary leadership system creates unique vulnerabilities. Economic reforms pose an existential threat to Kim’s regime, potentially destabilizing his rule by exposing his family’s repressive legacy, inviting external influence, and undermining his justification for nuclear development as a means of safeguarding his long-term power.

This fear explains Kim’s preference for aligning with Russia over China. Moscow exerts no pressure on Pyongyang to reform, and Putin lacks the personal grievances that have marred Kim’s relationship with Xi. For Kim, Russia offers a safer and more convenient partner.

China has responded to this pivot with subtle but telling signals of diplomatic cooling. The removal of the commemorative copperplate from the 2018 summit between Xi and Kim, along with replacing photos at the North Korean Embassy in Beijing with images of Kim Il Sung, indicate Beijing’s unease with Pyongyang’s evolving alliances. The photo replacement, almost certainly directed by Pyongyang, appears intended to remind Beijing of the historical strength of the China-North Korea alliance under Kim Il Sung’s leadership while subtly critiquing its current lack of full support for Kim Jong Un’s regime.

Additionally, China’s recent denial of visa renewals for North Korean athletes in its domestic leagues, signaling a reversal of the sports exchange protocol signed in January, underscores the increasingly strained relationship.

A less noted area of cooperation in which China has curtailed its engagement with North Korea is the repatriation of North Korean escapees. Since North Korea reopened its border to foreign nationals in late September 2023, China has repatriated over 700 North Korean escapees. China considers these individuals to be illegal migrants, and its refusal to grant them refugee status supports Kim’s political legitimacy.

However, since the Putin-Kim summit in June, China appears to be holding them in limbo, with public security officials reportedly having warned North Korean escapees living in China to lay low while substantially increasing surveillance of these vulnerable communities. Considering that public security cooperation between China and North Korea in this area has long been stable, the current delay becomes even more significant, signaling Beijiing’s considerable dissatisfaction with Pyongyang.

Additionally, Chinese state media did not mention the “Friendship Year” designation when reporting on the exchange of congratulatory messages between Xi and Kim, and no Xi-Kim summit was held this year despite some analysts’ prior expectations. Through these signals, China has not hesitated to demonstrate its willingness to target the Kim regime’s ideological legitimacy if pushed far enough.

In recent years, China has dramatically increased its economic influence over both Russia and North Korea. While the “no-limits” friendship with China has benefitted Russia, particularly in its invasion of Ukraine, it is unlikely that Putin will settle for being the subordinate partner indefinitely.

More notably, China now accounts for approximately 95% of North Korea’s total trade. Kim understands that if Beijing fully leveraged this economic weight, it could compel Pyongyang to alter its security policies and abandon its nuclear weapons program.

Beyond the immediate technical support and revenue that Russia can provide North Korea to fuel its weapons program, their alliance is also likely aimed at achieving long-term strategic autonomy from China. Given that Trump has promised to end the war in Ukraine and previously engaged in summit diplomacy with Kim, North Korea’s deployment of soldiers to Russia could be an effort to involve itself in a potential settlement, one that might bring it sanctions relief. Therefore, Putin and Kim are well aware that engagement with the new U.S. administration, one composed of prominent China hawks, could help to move them out from underneath China’s thumb.

This would be a nightmare scenario for China. China has repeatedly condemned the overlapping system of partnerships and alliances that the United States has spearheaded in recent years, particularly AUKUS, the Quad and, more recently, NATO and its Indo-Pacific Partners. If Russia and North Korea were to engage with the United States independent of China, such a move would substantially increase its long-standing fear of a U.S.-led encirclement by disrupting its relatively secure northeastern flank.

It has long been U.S. practice to urge China to exercise its influence over North Korea. However, the incoming U.S. administration should carefully reconsider this assumption in its diplomatic approach.

For Xi, Kim is an unpredictable liability. Kim’s refusal to embrace China’s model of reform and opening, combined with his relentless pursuit of nuclear weapons, has consistently transformed Northeast Asia into a flashpoint for regional arms competition. Despite North Korea’s strategic importance to China, Kim’s actions suggest a degree of independence from Beijing, complicating China’s ability to exert control.

While a second Trump term is likely to exacerbate U.S.-China economic tensions, it could also present a unique opportunity to secure Beijing’s cooperation on the North Korea issue. The current dynamics offer favorable conditions for advancing U.S. interests on the Korean Peninsula. Therefore, the Trump administration should adopt a dual strategy.

First, it should work with China to strengthen and enforce sanctions on North Korea while making relief contingent on Kim’s adoption of Deng Xiaoping-style economic reforms, allowing Beijing to take the lead in advocating for these changes.

Second, it must maintain U.S. commitment to the U.S.-Japan-South Korea trilateral security cooperation and continue to pressure North Korea on its human rights record. North Korea has always sought to leverage historic disputes between U.S. allies while opportunistically rebalancing its engagement between China and Russia. The trilateral security cooperation severely limits the regime’s ability to diplomatically maneuver in this regard and to continue its repressive domestic policies without enacting substantial reforms.

This policy approach offers a pragmatic path forward and tangibly advances U.S.-China shared interests. Ultimately, it will set the conditions to achieve denuclearization while allowing the northern half of the Korean Peninsula to remain within China’s sphere of influence. Such a strategy, balancing U.S. objectives with China’s regional priorities, holds promise for advancing peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula.

Seohyun Lee is a North Korean defector, human rights advocate, and aspiring security expert currently serving as a Research Intern at the Hudson Institute. She holds a Master’s degree in international security policy from Columbia University and has presented on esteemed platforms, including the UN Security Council in 2023. Her work focuses on East Asian geopolitics, human rights, and cybersecurity.

Michael Donmoyer worked as a research fellow for the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command’s Foreign Military Studies Office and the Congressional-Executive Commission on China. He is currently a graduate student at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies and is an alumni of the Hopkins-Nanjing Center. He is an Army veteran and spent over two years stationed in South Korea.

The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.