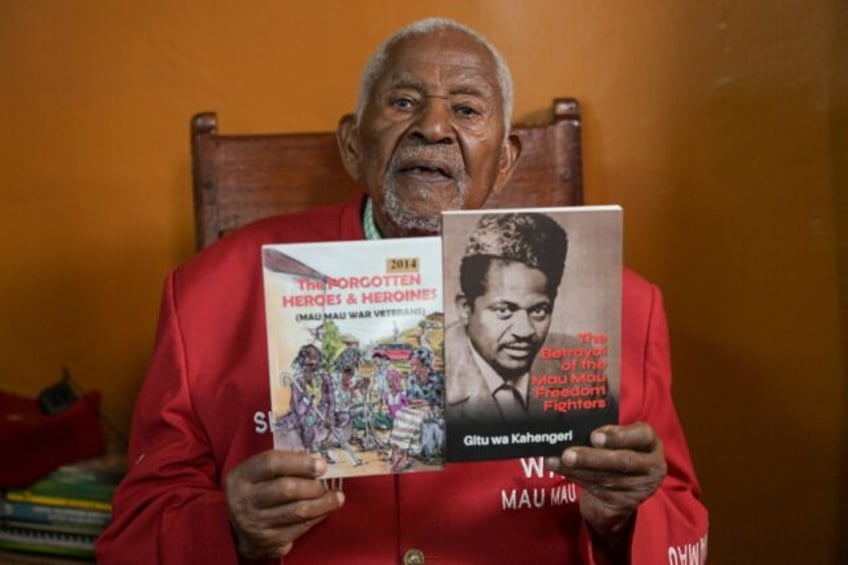

More than six decades after Gitu Wa Kahengeri was jailed, tortured and denied food in a British-run labour camp in Kenya, the anti-colonial fighter says he is still waiting for justice.

Now in his nineties, Gitu has ramped up his push for an apology and compensation from the British government as King Charles III visits the East African country.

Gitu left school as a teenager after a disagreement with the principal over his anti-colonial beliefs, later joining the feared Mau Mau rebels as a young man.

For nearly eight years the guerrillas — often with dreadlocked hair and wearing animal skins — terrorised white settlers, launching attacks from bases in remote forests.

“We fought to be free because the colonial settlers had grabbed all the fertile land and made it their own,” Gitu told AFP during an interview at his home surrounded by pineapple farms outside the town of Thika.

“The cruel… ill-treatment that was meted to the Africans by the colonial administration, I was one to suffer that.”

The rolling green hills and lush forests of central Kenya — once dubbed the “white highlands” — were especially prized by colonial settlers, sparking bitter resentment from Gitu’s ethnic Kikuyu people who were forced off the land.

Months after the rebellion kicked off in 1952, then British prime minister Winston Churchill declared a state of emergency, paving the way for a brutal crackdown.

Tens of thousands of people were rounded up and detained without trial in camps where reports of executions, torture and vicious beatings were common.

A year into the bloodshed, Gitu was arrested along with his father and sent to a remote Indian Ocean island.

“We left our children at home, suffering, having no food, having no medical care and having no education,” Gitu said, recalling his seven-year detention in painstaking detail, his sharp memory belying his age.

Horrific abuses

More than 10,000 people died in the Mau Mau uprising, a figure some historians claim is a low estimate.

Tens of thousands of Kenyans — many with no links to the Mau Mau — endured harrowing treatment including torture and appalling sexual mutilation at the hands of security forces.

Buckingham Palace said Charles and his wife Queen Camilla will “acknowledge the more painful aspects” of colonial history during their four-day state visit.

“His Majesty will take time during the visit to deepen his understanding of the wrongs suffered in this period by the people of Kenya,” the palace said.

But the symbolism of the visit — the first by Charles to a Commonwealth country since becoming king — is not lost on Gitu.

“If I were given a place and a chance to speak to the king… the first question I would ask him is why did you keep silent?”

A former legislator who was elected to parliament in 1969, Gitu called on Charles to “sincerely and voluntarily” return any artefacts taken from Kenya and go beyond the public statement of regret for abuses committed.

In 2013 Britain agreed to compensate more than 5,000 Kenyans who had suffered abuses during the revolt, in an out-of-court settlement worth nearly 20 million pounds (almost $25 million at today’s exchange rates).

Each claimant received around 2,600 pounds after legal costs were deducted.

Britain also funded a memorial to all the victims in a rare example of former rulers commemorating a colonial uprising.

But Gitu said the “small settlement” had done little to alleviate the poverty endured by most Mau Mau veterans and urged the British government “to do more to cultivate the reconciliation we are looking for”.

‘Not begging’

He also accused the Kenyan authorities of failing to give former fighters their due.

“None of the governments has looked after the freedom fighters in the way they deserved,” said Gitu, who also heads a Mau Mau veterans’ association.

“We are not begging, we are asking for our rights.”

Kenya’s founding president Jomo Kenyatta opposed the violence carried out by the Mau Mau, which created bitter divisions among communities, especially those who collaborated with colonial authorities.

Surviving fighters have accused successive Kenyan governments of neglecting them, with the group still outlawed until 2003.

In 2007, the government unveiled a statue of top Mau Mau leader Dedan Kimathi in Nairobi, half a century after his execution by colonial authorities.

Even as Gitu awaits a royal apology, Kenya’s treatment of the Mau Mau still stings.

“It is a great loss to have lost the education of our children, the good health of our children and in the end to have lost recognition.”