Last month, while in Nashville, Tennessee, to tape The Huckabee Show on TBN, I had the opportunity to visit The Hermitage, the country residence of Andrew Jackson, America’s seventh president and our nation’s original populist.

Jackson, together with President Thomas Jefferson, were once seen as forefathers of the Democratic Party. But the party dumped them over Jackson’s role in the displacement of Native Americans and Jefferson’s ownership of slaves.

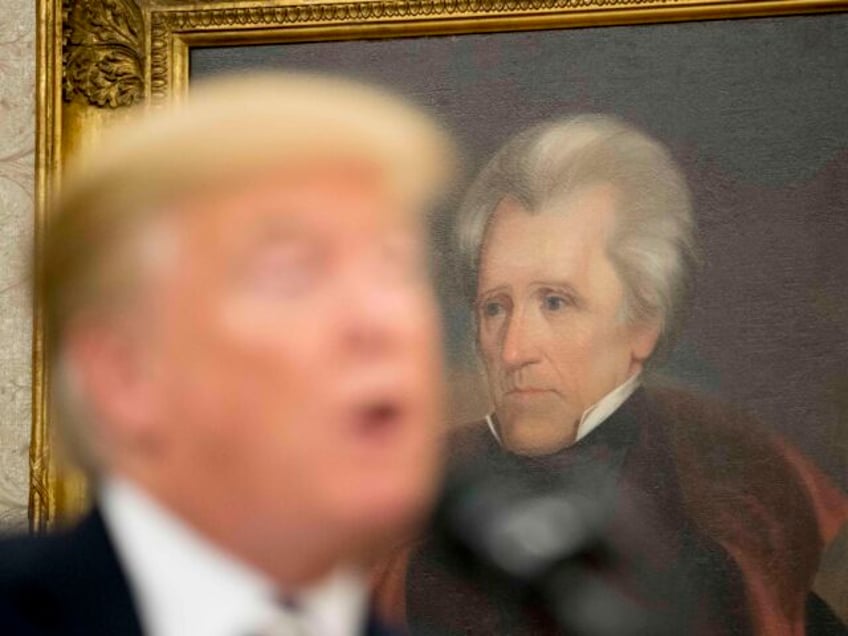

It was President Donald Trump who revived interest in Jackson, placing his portrait in a place of prominence in the Oval Office during his first term.

Trump, like Jackson, was opposed to the country’s established elites. But that was not the only similarity.

One observer noted that Trump’s working-class coalition resembled Jackson’s political base. Trump’s foreign policy was also said to be Jacksonian, in that it prioritized the national interest and the military.

Yet it was one word that was said to connect Trump to Jackson: populism.

It is a difficult word to define: it refers to rule by ordinary people, but populist leaders can also be demagogues who exploit popular sentiment to seize power.

Populist economic policy often favors redistributing the wealth of the rich to the poor, an approach that has proven disastrous. It is sometimes associated with protectionism that hurts trade and allows insiders to enrich themselves.

Trump’s version of populism — sometimes referred to as nationalist populism in these pages — is somewhat different.

While Trump raised some taxes on the rich in his first term — contrary to Democratic Party propaganda — he did not do so as part of a redistributive policy, but rather to create economic growth for all.

Trump championed tariffs, and continues to do so, but in a circumstance when foreign competition from China has become a national security risk.

Trump’s slogan, “Make America Great Again,” is focused on the nation as a whole, and evokes what was once called “national greatness conservatism” (many of whose proponents, associated with Republican elites, now abhor Trump).

The word “again” emphasizes that Trump’s populism is conservative, seeking to restore shared ideas, achievements, and optimism to a society that was once more confident in itself.

He wants to undo institutions — but save the nation.

Jackson’s Hermitage shows few signs, at least at first, of the populist ethos that defines his legacy.

“Old Hickory,” who once led a ragtag army of volunteers from the backwoods of Tennessee to defend New Orleans from the British in the War of 1812, built a stately mansion with neoclassical columns.

He also put up luxurious wallpaper, imported from France, that depicted scenes from Greek mythology. He maintained a grand library — and a large workforce of slaves.

It is in the family garden that the deeper side of the man emerges.

Jackson adored his wife, Rachel. She saw him win the 1828 election — a redemptive victory, after having been robbed by Northeastern brahmin John Quincy Adams in 1824. But she died before he took office.

Jackson wore a black band around his hat for the rest of his life and neither married nor courted ever again. The two are buried together in the garden.

Rachel’s grave bears this startling epitaph, which testifies to the deep love that her husband had for her:

Here lie the remains of Mrs. Rachel Jackson, wife of President Jackson, who died December 22nd 1828, aged 61. Her face was fair, her person pleasing, her temper amiable, and her heart kind. She delighted in relieving the wants of her fellow-creatures, and cultivated that divine pleasure by the most liberal and unpretending methods. To the poor she was a benefactress; to the rich she was an example; to the wretched a comforter; to the prosperous an ornament. Her piety went hand in hand with her benevolence; and she thanked her Creator for being able to do good. A being so gentle and so virtuous, slander might wound but could not dishonor. Even death, when he tore her from the arms of her husband, could but transplant her to the bosom of her God.

Reading that inscription in the crisp autumn air, I understood something new about Andrew Jackson: he had a deep capacity for love, so deep that he showed that grief to all who met him, whether in the White House or the Hermitage.

Jackson’s populism grew from that love. However flawed his policies, he loved his country not just for what it could be, but also for what it was.

That is the core of populism — a love that Trump, for all his flaws, shares as well.

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News and the host of Breitbart News Sunday on Sirius XM Patriot on Sunday evenings from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m. ET (4 p.m. to 7 p.m. PT). He is the author of The Agenda: What Trump Should Do in His First 100 Days, available for pre-order on Amazon. He is also the author of The Trumpian Virtues: The Lessons and Legacy of Donald Trump’s Presidency, now available on Audible. He is a winner of the 2018 Robert Novak Journalism Alumni Fellowship. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.