The digital euro will be one of the most private forms of electronic payment, according do a data protection official from the European Union.

On Oct. 2, 2020, the European Central Bank (ECB) released a report laying the groundwork for its central bank digital currency (CBDC), the digital euro.

The digital euro has been in its investigation phase since October 2021, during which ECB officials and bankers hypothesized about its possible design and purpose.

As of November 2023, the digital euro has entered the preparation phase, with possible legislative adoption expected by the last financial quarter of 2024.

If the ECB can stick to its roadmap, digital euro use cases could roll out by November 2025.

Despite still being in development, the digital euro is already facing resistance over privacy concerns.

Maarten Daman, a data protection officer at the ECB, claimed in a June 13 blog post that the ECB is “designing the digital euro to be the most private electronic payment option.”

To achieve this goal, the ECB must offer assurances to gain the trust of EU citizens to use the CBDC. Daman spoke with Cointelegraph to about the issue, where he stressed that the ECB has no hidden agenda:

“We are committed to being as transparent as possible regarding the privacy aspects of a digital euro as our analysis progresses. We have nothing to hide.”

Tackling the digital euro’s privacy issue

Most Europeans remain uninformed about the digital euro. A June 6 survey from Germany’s central bank, the Deutsche Bundesbank, found that 59% of respondents knew nothing about it.

The ECB has a prime opportunity to form the digital euro’s narrative for most Europeans.

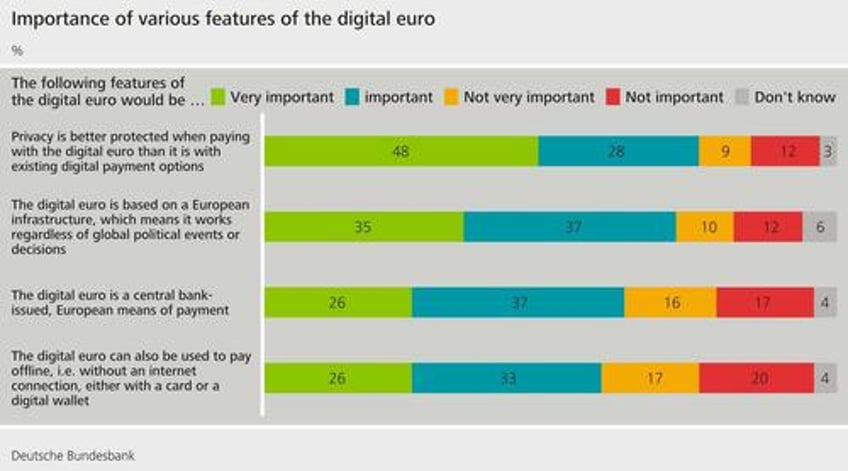

The Bundesbank survey found that despite the widespread ignorance about the digital euro, three-quarters of respondents rated privacy regarding using the digital euro as very important or important.

Importance of various features of the digital euro. Source: Deutsche Bundesbank

In a 2024 progress report on the digital euro, the ECB said it would not collect financial data from clients. However, it will gather some data to comply with Anti-Money Laundering (AML) regulations. Daman said there are strong efforts to create a digital euro that requires the least data possible:

“As a principle, the Eurosystem’s starting point is to process only as little as possible personal data required to fulfill our objectives.”

The ECB report mentioned how it is exploring technological solutions — namely pseudonymization — so that the Eurosystem, the issuer and payment infrastructure provider, can’t directly link transactions to specific individuals.

Pseudonymization enhances privacy by replacing identity attributes with fictitious ones, thus hiding personal identities. This process allows authorities to analyze data without being directly traceable to individuals, maintaining the data’s usefulness in transaction processing while protecting individual privacy.

The pseudonymization strategy aligns with that of Richard Brown, R3’s chief technology officer, who specializes in enterprise blockchain and CBDCs.

Brown told Cointelegraph that an elegant solution to the digital euro’s privacy problems would involve private firms unrelated to the government managing customers’ direct commercial relationships as their personally identifiable data. He said that “identifiable data would be kept away from the core record of financial transactions, also known as the ledger.”

Brown said the ECB would only provide the core infrastructure and ledger for a digital euro while private firms would act as wallet providers. This infrastructure “would ease privacy concerns, especially if the privacy promises were backed by the force of law,” he said.

The ECB pseudonymization approach follows this route, as the Payment Service Providers in charge of handling citizens’ data would have a segregated data stream with the Eurosystem, making it impossible to directly identify end-users or link any of the data it processes to a determined end-user.

Could the digital euro offer a backdoor for governments?

Concerns remain that governments could have a backdoor into user data, as some information needs to be shared with authorities to satisfy AML regulations.

Daman acknowledged the concern but said that a number of mechanisms would prevent this from happening:

“The Eurosystem would not be technically able to directly identify digital euro users, track their payments, nor legally allowed to do so, nor would we have a commercial incentive as a public institution.”

Daman said the ECB “will adhere to the digital euro’s legislation. The proposal explicitly prohibits us from processing personal data to directly identify users.”

The ECB would be overseen by the European Data Protection Supervisor, an independent institution that supervises EU institutions and has the power to conduct audits and inspections.

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) will intervene if the law is breached. If an EU act is believed to violate EU treaties or fundamental rights, such as the right to privacy, the ECJ has the power to annul it.

The ECJ has a history of defending privacy rights. The court invalidated the Safe Harbor (2015) and Privacy Shield (2020) frameworks — which provided data transfers between the EU and the United States — after it found that these agreements did not adequately protect EU citizens’ data from US government surveillance.

Digital euro skeptics still don’t trust the project

Fiat currencies like the dollar or euro rely on the public’s trust in the issuer. Daman said that trust and privacy are core aspects taken into account for the digital euro:

“High levels of privacy and trust will be key aspects that distinguish a digital euro from other currently available payment solutions.”

Richard Turrin, author of Cashless: China’s Digital Currency Revolution and an influencer focused on CBDCs, told Cointelegraph that he believes “the ECB’s messaging on privacy is spot on, and their claims that the digital euro will be more private than existing card-based payments are true.”

However, he said that once the ECB launches the final design, “we’ll all need to take a look to ensure their claims of privacy, but they’re off to a good start.”

Despite the assurances offered by the ECB backed by solid laws and supervising authorities, mistrust remains.

Joana Cotar, an independent German member of parliament and organizer of the awareness campaign Bitcoin im Bundestag, told Cointelegraph that history has demonstrated several cases where states repeatedly used new technologies against people.

Cotar said, “Risks are succinctly dismissed concerning legal frameworks that are supposed to rule out any abuse.” She noted how “the ECB does not mention that such laws can be rewritten or circumvented.”

“I believe that blind faith in the ECB is reckless. No matter what political promises have been made.”

Josh Swihart, CEO of Electric Coin Company, which created the privacy coin Zcash, claims that the CBDC design allows issuers to have “visibility into balances and transactions and to be able to take action such as blacklisting addresses or freezing funds.” He told Cointelegraph that under such a structure, complete financial privacy isn’t guaranteed:

“Privacy is not binary; it’s a gradient.”

Swihart highlighted how governments could mandate the use of their centrally controlled currency and suppress alternatives, such as privacy-protecting crypto.

The ECB has repeatedly stated that the digital euro is not intended to substitute other payment solutions and that a government mandate won’t enforce the use of the CBDC. Despite the ECB’s good intentions, Swihart believes that “even if the control is not exercised abusively today, it’s a slippery slope.”

He highlighted how “power doesn’t typically cede power,” adding that “once an individual gives up their rights to governments, it typically leads to greater invasions of freedom rather than less.”