By Bas van Geffen, senior macro strategist at Rabobank

Just two weeks have passed since the sharp deterioration in the US employment report sparked a sharp sell-off, but concerns seem to have faded: we’re back on track for Goldilocks. And, Bloomberg reports, the “carry trade that blew up markets” is finding new appeal. Have we collectively forgotten what happened only two weeks ago?

[ZH... spoiler alert yes, as we noted 3 days ago]

Someone tell the USDJPY the carry trade is 100% back on

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 13, 2024

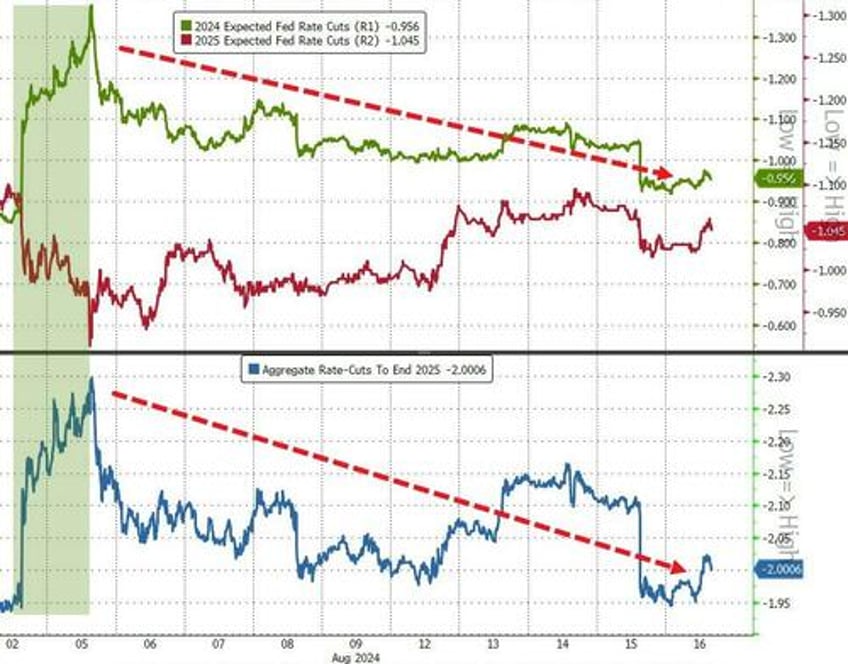

In any case, the emergency and outsized rate cuts that were being priced in have made way for a cutting cycle that looks a lot more plausible. Yesterday’s US data helped to further erase some of the market-implied odds of big rate cuts.

Both initial and continuing jobless claims dropped again, easing concerns that the labor market is deteriorating as rapidly as the latest non-farm payrolls suggested. Of course, there are several potential caveats to these statistics. Migration has plagued labour market data for some time now, leading to discrepancies between indicators of labor market tightness. That may be no different with the jobless claims: immigrants may not qualify for unemployment insurance, and so, if they are laid off, this may not be captured in the jobless claims.

Despite these caveats, markets are taking the glass half full view on the claims data. The market-implied probability of a 50bp Fed cut in September -rather than a regular 25bp reduction- dropped from 40% to around 30%. But rate repricing was seen along the curve, with the 2 year Treasury yield up 14bp on the day and the 10 year yield 8bp higher.

That positive approach may be further supported by stronger-than-expected July retail sales. Last month, US consumers spent more than anticipated. Retail sales rose 1% on the month. So the consumer may be a bit more resilient than expected, even if the underlying trend indicates some weakening. Particularly, households held back on big discretionary spending and mostly bought essentials. The largest chunk of the increase in retail sales came from cars. Excluding that category, groceries made up for the biggest part of the increase in sales. Without cars, gas, and groceries, retail sales slowed to 0.3% m/m, after a 0.9% increase in the prior month.

So the bigger picture of a slowing, but not crashing, US economy appears to be re-established. Interestingly, money market participants do continue to price a steeper cutting cycle in the US (-95bp through December) than in Europe (-64bp). Even so, the market-implied probability of a rate cut at each of the three remaining ECB meetings remains elevated in our view.

Although the ECB had adopted “a slightly more cautious outlook for productivity growth” in its June projections, productivity per employee still falls short of their assumptions. Data published by the ECB yesterday show that labour productivity declined by 0.4% y/y in Q2; falling short of the -0.3% embedded in the staff projections.

Following the July policy meeting ECB President Lagarde stated that “We believe [domestic prices] are largely determined by what I call the WPP, which for me is the wage, the profit and the productivity.” She continued that the central bank expects productivity to improve gradually, as a pick-up in consumption forces hoarded employees to respond to the increased demand for goods and services. That should lead to lower costs per unit of output.

The sluggish recovery so far should raise some concerns that labor productivity may not rise as quickly or as high as the ECB expects it to. The central bank projects productivity gains of about 1% in both 2025 and 2026. That is substantially above the 0.5% average annual productivity increase since 2000, even if hoarded and currently sidelined employees are brought in to actually do more work. Should productivity fall short of these estimates, inflation could remain sticky for longer than the ECB expects.

The miss in Q2 may not be significant enough to force an upward revision in the inflation forecasts at this juncture (productivity growth was marginally higher than the ECB projected in Q1). But if it does lead to a somewhat higher inflation projection, that could paint an awkward backdrop to a September rate cut: it would be the second time that the ECB lowers its policy rates while its inflation forecast is revised up. The ECB is not a prisoner to these forecasts, but it would raise questions about its data dependence – unless the ECB has suddenly turned much more pessimistic on the growth outlook.

Our bottom line: whether it materially alters the September forecasts or not, these productivity figures warrant caution about the inflation outlook and an additional rate cut in October still seems like a pretty big gamble.