A bipartisan group of top Republicans and Democrats from the tax-writing committees in Congress reached agreement this week on a $78 billion package that would expand a tax benefit that provides money to parents and restore three popular expired business tax breaks. That combination offers both parties an opportunity to claim wins as voters begin to head to the polls ahead of the election in November.

Specifically, on Tuesday, Senate Finance Committee Chairman Wyden (D-Or.) and House Ways and Means Chairman Smith (R-Mo.) announced an agreement to expand the child tax credit (CTC) and reinstate corporate tax provisions that the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) made less generous. Limits on further claims of the COVID-related employee retention tax credit (ERTC) would provide savings to reduce the budgetary impact of the changes.

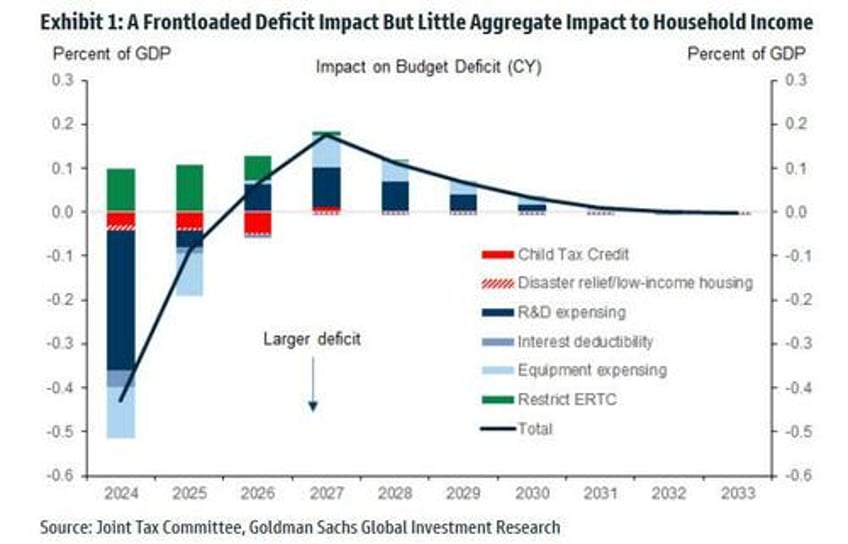

According to an analysis by Goldman, the deal, which expand the child tax credit (CTC) and restore business tax incentives, reduces revenues by $78bn (0.25% of 2024 GDP) over ten years and leads to a bigger increase in the near-term deficit. Limits on the COVID employee retention tax credit (ERTC) would supposedly offset the budgetary impact, but that is certainly not the case, especially not in the near-term.

While the proposal boosts deficit spending by tens of billions, it looks unlikely to materially affect the growth outlook. The child tax credit expansion looks likely to boost 2024 personal income by less than $10bn, with a good chance it has essentially no impact this year if Congress does not enact it in time to affect the upcoming tax filing season (i.e., in the next few weeks). Limitations on ERTC claims would likely reduce tax refunds by a larger amount so, while the effect on low-income households might be positive, the net impact on overall personal income in 2024 would be more likely negative.

By contrast, Goldman calculates that corporate tax changes would result in a larger near-term reduction in cash taxes than the ten-year estimates suggest. The three main changes — a restoration of R&D expensing, 100% bonus depreciation, and more generous interest deductibility — would apply retroactively and could reduce net corporate tax receipts in CY2024 by around $140bn (0.55% of GDP). As these policies shift the timing of tax payments much more than the cumulative amount, the ten-year impact would be substantially less. For the same reason, these policies would likely have a limited positive impact on investment, particularly as many businesses likely expected these retroactive changes to pass at some point.

Here are some more details on what is included in the corporate side of the tax bill:

- Full expensing of R&D costs: To raise revenue to offset other business tax cuts, TCJA changed the tax treatment of R&D expenses. Rather than writing off costs in the year businesses incurred them, starting in 2022 the TCJA requires them to be amortized over 5 years. The current proposal would reverse that change, retroactive to 2022. This would reduce net cash taxes in 2024 by around $90bn—tax refunds for 2022 and 2023 and lower estimated taxes for 2024—even though the 10-year impact would be much smaller (companies would pay less tax now and more tax later);

- Extension of 100% bonus depreciation: The TCJA allowed businesses to immediately deduct 100% of the cost of capital equipment through 2022, but this phases down to 80% in 2023 and 60% in 2024. The bill would restore the 100% immediate deduction. This would likely reduce net corporate tax receipts by around $40bn in CY2024, but would increase receipts a few years from now, so like the R&D change the longer-term cost would be much smaller than the near-term effect.

- More generous interest deductibility: The TCJA limits corporate interest deductibility to 30% of EBIDTA through 2021 but then shifts to 30% of EBIT from 2022. The bill would reinstate the more generous EBITDA-based limitation through 2025. This would reduce net corporate tax receipts in CY2024 by around $10bn.

There is a clear chance that Congress will pass a tax bill similar to this in the near-term, but the odds are against it. There are three arguments in favor of passage.

- First, the Republican chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee and the Democratic Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee have both agreed to these changes, and several other members of both parties appear to be in support.

- Second, both parties get something out of the deal: most Republicans support the business tax incentives, while nearly all Democrats have sought an expanded child tax credit.

- Third, passing the bill now has benefits that won’t be available after this year: if passage is delayed until next year when Congress takes up expiring 2017 tax cuts, the odds of retroactively extending business tax breaks back to 2022 are likely to be lower. Similarly, the means of paying for the current proposal—limiting ERTC claims—will no longer produce any savings next year, as the deadline to claim the credit is June 2025.

The arguments against near-term passage are stronger according to Goldman economist Alec Phillips: while there appears to be plenty of support on both sides of the aisle, there is also plenty of opposition. Most Democrats prefer a greater expansion of the child tax credit—the proposed expansion is worth around 10% of the value of the 2021 policy enacted as part of the American Rescue Plan (ARP)—and object to providing much greater near-term tax relief to businesses than low-income households. On the Republican side, many are likely to object to loosening the relationship between income and eligibility for the child tax credit and are unlikely to be enthusiastic about extra payments to households ahead of the presidential election with a Democratic incumbent in the White House. And while using the ERTC limits to offset and making business tax incentives retroactive becomes harder with a delay, Congress could probably still pass a substantively similar proposal late this year in a lame-duck session of Congress.

The House Ways and Means Committee is scheduled to debate the package Friday, and while an agreement between the chairmen of the two relevant committees raises the odds that a tax bill passes, we are still skeptical the bill will become law quickly as noted above. It looks likely to take several weeks more at a minimum, which would likely be too late to affect the upcoming tax filing season. If such a tax bill does become law this year, it might not happen until after the presidential election in a lame duck session of Congress.

More in the full Goldman analysis available to pro subscribers.