By James Crombie, Bloomberg Markets Live writer and strategist

Wafer-thin spreads on corporate debt don’t matter — until they do. There are several potential triggers for risk premia to flare, denting credit portfolios.

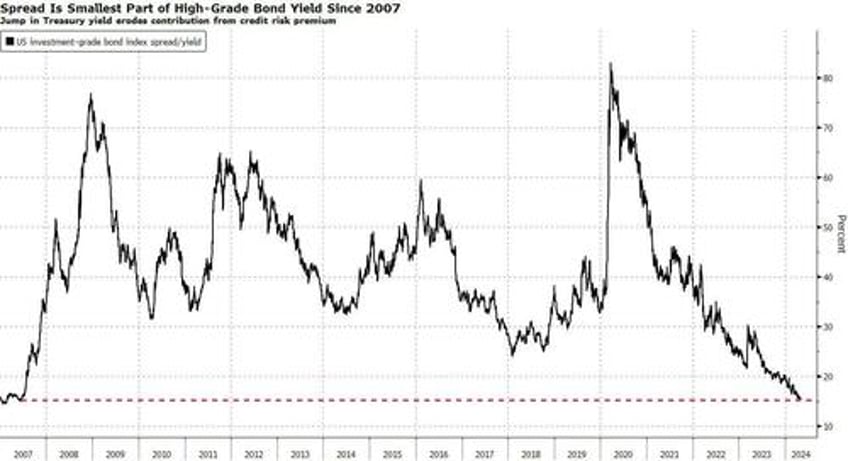

Spreads have collapsed across the board, from investment-grade and junk bonds to collateralized loan obligations. The extra yield investors get for owning US high-grade corporate debt instead of government bonds is the lowest in two-and-a-half years.

At less than 90 bps, that’s far below the five-year average of about 120 bps. As a percentage of all-in yield, it’s the least since 2007.

Such narrow risk premia reflect booming demand for limited net new supply of corporate bonds, plus a general lack of concern about the macroeconomic outlook. And since the Federal Reserve bailed out corporate bonds during Covid, there’s a perceived central bank backstop underpinning the debt.

Buyers have been lulled into thinking this is the new normal, but such a paltry yield pickup doesn’t adequately reflect rising corporate credit risk. So when volatility returns to jolt investors from their slumber, expect credit risk premia to flare, slamming portfolios.

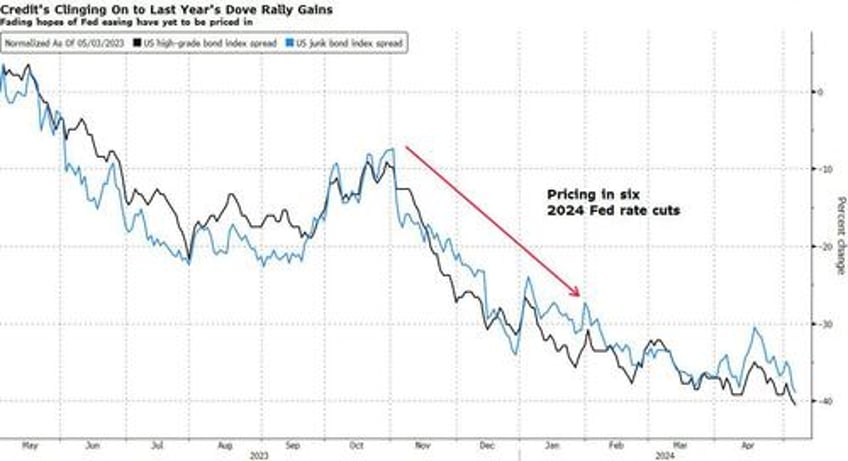

Credit typically tracks broad measures of volatility, with spreads widening when markets get choppy. But since December, when corporate bond buyers were bulled up on the idea of six 2024 rate cuts and a soft landing in the US, they’ve diverged.

There are eerie similarities with the period just before the global financial crisis — not least high-grade spreads and bond yields at around the same levels. After that particular bubble popped, investment-grade risk premia spiked above 600 bps.

Other credit blow-ups occurred during the 2011 European sovereign debt crisis, a 2016 rout in the banking sector and oil prices, as well as during the global economic shutdown when the coronavirus spread in 2020.

War, geopolitics and elections are reasons to believe the VIX Index will rise closer to its five-year average above 20, from less than 14 currently. That should rattle credit investors, who are increasingly exposed by accepting less cushion for rising risk.

In addition, credit’s vulnerable to a sustained exodus of funds fleeing negative returns — high-duration corporate bonds lose money when yields rise — in search of better options at more generous yield spreads. Plus there’s the threat of policy error — or even a hike — from the Fed, and a US recession can’t be ruled out. Both would throw debt portfolios for a loop.

Credit’s set up for a fall after rallying hard at the end of 2023. Investment-grade US bonds booked the best returns since 2008 in November and December, when investors raced to price in a whopping six rate cuts for this year. Barely any of that’s been given back — even as those dovish hopes have crumbled.

Ironically, the only place credit investors appear to have exercised some caution is in the very junkiest debt, which is most likely to inflict pain as rates stay high for longer. Risk premia on bonds rated CCC have tightened 60 bps this year, or 8%. That compares with a 13% contraction in high grade.

Of course, a steady US economy is good fundamental news for borrowers and a strong bid for yield provides support. But earnings are eroding — particularly at financials, which are 30% of the market — and interest-coverage ratios are creeping up as high-for-longer rates take their toll, even on better-quality borrowers.

Spreads may well grind even tighter as fat yields juice demand for limited net supply of new bonds. But that’ll only magnify the scale and pace of the inevitable flare up when volatility spikes and credit reverts to something more closely resembling long-term averages.