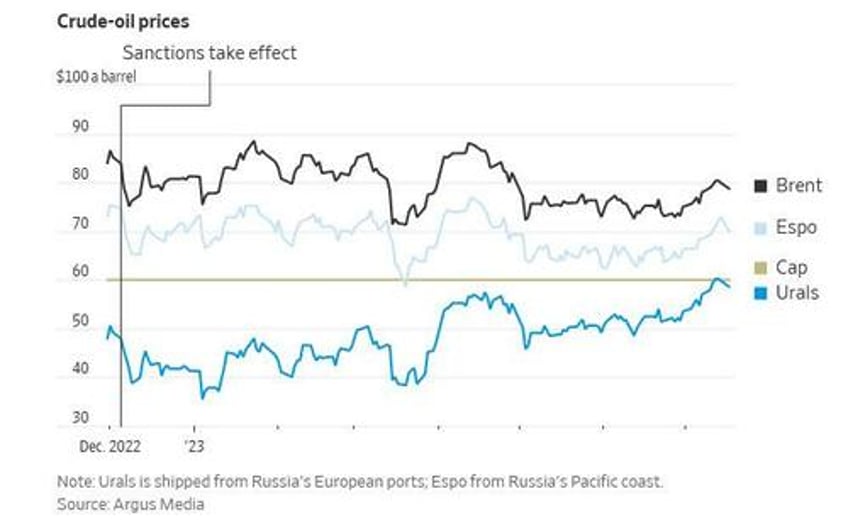

Two weeks ago we reported that with a barrel of Urals about to rise above $60, the "Russian oil price at key port was about to breach sanctions cap", which - if the sanctions were strenuously enforced - meant that there would be a sharp drop in supply.

Fast forward to today when, as the WSJ reported, the price of Russia's most coveted crude finally traded above the western price cap imposed to starve Moscow of funds for the war in Ukraine (but not really, because starving the world of Russian oil has long been viewed as a far more dangerous outcome), resulting in a very distinct "victory" for Moscow in the "fight for influence over global oil markets."

It is the first time that the price for its flagship Urals grade of oil has breached the $60-a-barrel limit since the U.S. and its allies introduced the novel sanctions policy last December, according to commodities-data firm Argus Media, and - as the WSJ clarifies - it is a sign that the Kremlin has succeeded, at least in part, in adjusting to the restrictions.

As a reminder, in late 2022, companies in the Group of Seven advanced democracies were allowed to transport and insure Russian crude only if the price is below $60 a barrel. There are separate caps for refined products. The idea is that Moscow will sell petroleum at lower prices because it needs Western services to export its oil, thus keeping commodity inflation low.

The cap is part of a Western economic-pressure campaign and targets Russia’s most important revenue source. It is meant to bleed the Kremlin’s war coffers while encouraging Russian producers to keep sending petroleum to market so as not to foment inflation around the world. However, in a world where Russia's 7 million of barrels of daily oil exports are suddenly pulled from the market, inflation would explode as the price of oil would promptly soar, we learn just how toothless western sanctions have been... and were meant to be.

One sign that the financial squeeze on Moscow might be relenting: The discount for Urals, compared with benchmark Brent, has narrowed to $20 a barrel. The gap is still far wider than before the war, but it has halved since January.

Meanwhile, the higher prices will bolster Russia’s oil-export revenues, which last month dropped to just over half their level from a year ago, according to the International Energy Agency, leading to more money available to fight the war in Ukraine just Zelensky's counteroffensive is about to collapse. Russia's Urals crude, named after the mountainous, oil-rich region, has also gotten an extra boost from high demand in Asia, where Russian producers are elbowing aside Saudi oil.

With Urals, Sokol and ESPO trading now above the $60-a-barrel level, we should **assume** that all Russian crude is now flowing into the global market without using Western banking, insurance and shipping. Either that, or "attestations" are getting rather creative | #OOTT

— Javier Blas (@JavierBlas) July 24, 2023

Western sanctions strive - at least on paper - to use Russia’s longstanding dependence on European shipping and insurance as leverage to contain the income Moscow fetches from crude. Climbing prices suggest Russia’s push to assemble an alternative network of tankers to which sanctions don’t apply is eroding Western influence over its prize export, said Sergey Vakulenko, an analyst at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center and former oil executive in Russia.

“This was an evolutionary process, and now we just see its results,” said Vakulenko. “Russian oil companies…put quite a lot of effort into staying in business and earning money. They have proven themselves to be capable operators.”

According to the WSJ, traders said Russian producers recently showed little desire to negotiate prices at which Western players could stay in the market. That is a shift since Urals last neared $60, in April.

To be sure, Russian companies are likely to need Western ships and insurance for some time to export some of the more than seven million barrels of petroleum they sell overseas daily. Some analysts say that gives the U.S. and Europe significant—though waning—leverage, and that they could step up the financial pressure on Moscow by lowering the cap. However, the growing influence of the gray fleet if "mystery" middlemen- which has shown remarkable stoicism to Washington's sanctions threats - is what has given Putin all the leverage he needs. In the end, the $1 billion monthly windfall talks, and Biden's bullshit walks.

Unable to accept defeat, Washington officials call the price rise a Pyrrhic victory for Moscow and point to the many obstacles that have been thrown in Russia’s way.

“Fundamentally, the price cap is holding down Russia’s revenue significantly, while continuing to create a world in which global markets are being supplied with Russian oil,” Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo said in an interview. “Our goal is to continue to increase the cost for Russia in order to make sure they have less money to fight their illegal war in Ukraine, and that’s happening every day.” Spoiler alert: what is happening is that Russia is not only countering Ukraine's "counteroffensive" but is now making the most money per barrel sold to foreign buyers in all of 2023.

And now that the western sanctions have shattered, the blame game begins: critics say allies started with the cap too high. Ukraine, backed by close allies including Poland, has lobbied to reduce it. But disagreements inside the European Union and concern about gas prices in Washington stymied them.

Instead, according to the WSJ the U.S. and EU have focused on tightening enforcement. A focus: The laundering of oil through swaps between ships at sea. Fraudulent documentation and side payments have also been used to evade the cap, according to traders.

However, the real goal of the sanctions was to fool the public that the West was doing something to punish Putin when in reality the imperative was to make sure Russia does not pull its oil from the western market and sends the price soaring.

A bigger challenge for the sanctions is the new logistics system that Russia and companies in its orbit began to build, consisting of tankers owned, insured and chartered outside the West.

As reported previously, sales of secondhand tankers have swollen the shadow fleet—industry parlance for tankers that shuttle petroleum from sanctioned nations. In the second quarter, five times as many tankers worked with sanctioned producers than at the end of 2021, according to ship-tracking firm Vortexa. Almost 80% of those ships have plied the Russian market.

The West derived leverage in part from the outsize role played by the shipping industry of Greece, which as an EU member observes the sanctions and price cap. The country’s tanker fleet moves more than half of crude exported from Russia, said Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance. “The West has true pricing power,” he said, adding that the cap could be lowered to between $20 and $30 a barrel. Of course, at that price Russia would sell zero oil to the west and instead target just India and China, which in turn would lead to a violent explosion in Western oil prices, something the former Goldman FX trader clearly failed to anticipate (not that surprising when one looks at the track record of his FX trading recos during his Goldman tenure).

Meanwhile, as even the WSJ admits, what little leverage the West has is evaporating. The huge sums European tanker companies could earn from renting ships out to move Russian oil have fallen in recent months, suggesting Russia has growing access to tankers owned outside the G-7, said Henry Curra, head of research at shipbroker Braemar.

At Russia’s Asian port of Kozmino, where a flavor of crude called Espo has traded above the cap all along, few tankers insured or owned by companies in the West are now involved in the oil trade.

The Biden administration acknowledges that Russia is developing an independent fleet, but a senior Treasury official said it isn’t a significant driver of oil flows. The cost of creating that alternative export system diverts funds from the war, U.S. officials say. They estimate that Russia’s central bank has deployed $9 billion to replace Western reinsurance schemes.

U.S., European and Japanese insurers covered almost all of Russia’s seaborne exports before the war, including those on Moscow’s state-owned tankers. Known collectively as the International Group of P&I Clubs, these companies insure against claims from third parties, such as coastal industries affected by an oil spill.

By April, half of Russian crude shipments and a third of refined-product shipments were on tankers not insured by members of the International Group, according to Borys Dodonov of the Kyiv School of Economics.

Rolf Thore Roppestad, chief executive of Norwegian insurer Gard, said at least 10 tankers pass through the Danish straits, Suez Canal and Strait of Malacca daily without International Group insurance. That poses dangers, he said, because insurers outside the group mostly lack experience in responding to accidents.

“The concern is that these insurers may not have backing by reinsurers—or, to the extent they do, those reinsurers may not have the resources to meet a major claim,” said Alexander Brandt, a partner at law firm Reed Smith. If there is a spill, he said, “the fear is that there will be no one there to mop it up—literally.”