This investigation was done in collaboration with Environmental Progress and The Blind Spot

Last August, in an amalgamation of “The Green New Deal” meets “Build Back Better,” President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act gifted the renewables industry with billions of dollars worth of taxpayer-funded subsidies.

What few backing the bill realized was that the largest beneficiary would likely be China due to its expansive grip on the global solar photovoltaic (PV) industry. Worse than that, it might end up misdirecting the world’s clean energy efforts into dirtier than appreciated energy technologies because of the country’s ongoing dependence on coal-fired energy.

Information unearthed by Environmental Progress, a nonprofit research organization, points to a gaping oversight in how the figures influencing government net zero policy and investments in solar worldwide are compiled and collated due to the difficulty of collecting accurate information out of China, especially for the purification processes used to create silicon wafers.

The key to this blind spot is that a small number of data compilers provides the source material for most of the assessments. And many, if not all, of them work in collaboration with the International Energy Agency (IEA). The industry voluntarily submits the data in response to academic surveys. The nature and profile of the respondents are never publicly revealed, so there is the potential for conflicts of interest to develop.

A further puzzle is how that data feeds into an organization called Ecoinvent, a Swiss-based non-profit founded in 1998 that dubs itself “the world’s most consistent and transparent life cycle inventory database.” This data is relied on by institutions worldwide, including the IPCC and IEA itself, to calculate their carbon footprint projections, including the sixth assessment report published as recently as March 2023.

Based on such data, the IPCC claims solar PV is 48 gCO2/kWh. But, as we’ll see below, a new investigation started by Italian researcher Enrico Mariutti suggests that the number is closer to between 170 and 250 gCO2/kWh, depending on the energy mix used to power PV production. If this estimate is accurate, solar would not compare favorably with natural gas, which is around 50 gCO2/kWh with carbon capture and 400 to 500 without.

China’s Dirty Fuel Advantage

Over the course of a four-month investigation, Environmental Progress has confirmed that Ecoinvent — perhaps the world’s largest database on the environmental impact of renewables — has no data from China about its photovoltaic industry. Meanwhile, the ultimate source of the IEA’s supposedly public data on PV carbon intensity is confidential, and the data, therefore, is unverifiable.

Much of the cradle-to-grave carbon intensity data that governments depend on to guide photovoltaic arrays are instead based on modeling assumptions that are likely to have grossly under-estimated — if not made up — solar’s carbon emissions because they cannot get insights from Chinese manufacturers.

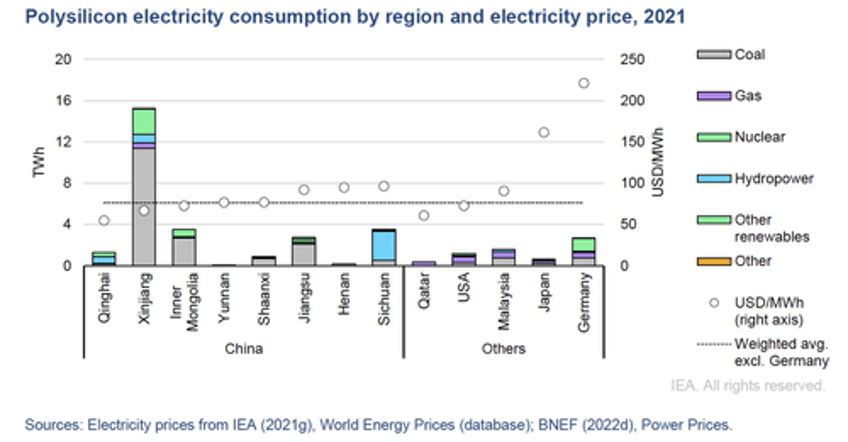

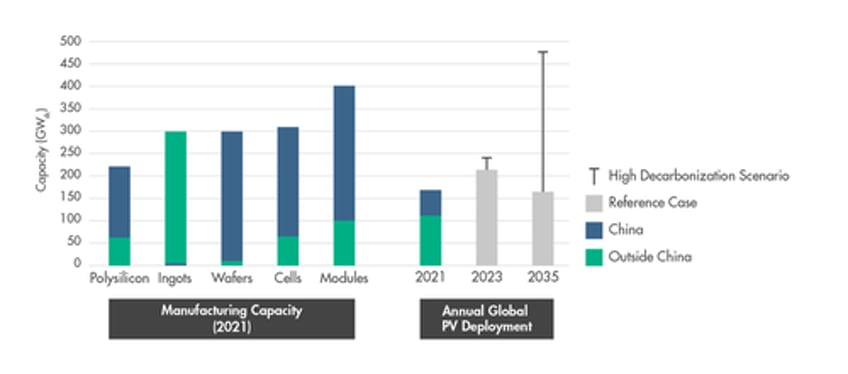

In its most recent report, the IEA predicts that China will continue to dominate solar energy production, delivering over 50 percent of solar PV projects globally by 2024. This trajectory is especially concerning given that China already commands most solar panel production.

The IEA noted that in 2022 China’s manufacturing capacity for wafers, cells, and modules rose 40-50 percent and almost doubled for silicon. In fact, according to market intelligence firm Bernreuter Research, in 2021, China produced more than 80 percent of global solar-grade polysilicon, a critical input into solar arrays. It doesn’t stop there; China manufactures 97 percent of the global supply of solar wafers, another essential component.

How China amassed that market concentration remains an inconvenient truth, all too readily swept under the rug by those pushing for net zero policies.

What we know for sure is that up until the mid-2000s, the market was dominated by Japanese, US, and German manufacturers, many of whom were in the midst of automating their production lines, when Chinese manufacturers swooped in to take their market share. The disruption happened in under a decade, with China’s global share of PV production surging from 14 percent in 2006 to 60 percent by 2013.

But the majority of experts consulted by Environmental Progress agree that China’s competitive advantage did not lie in an innovative new technological process but rather in the very same factors the country has always used to outcompete the West: cheap coal-fired energy, mass government subsidies for strategic industries, and human labor operating in poor working conditions.

Basic reasoning suggests the manufacturing shift must have added to solar’s carbon intensity. But as Environmental Progress has learned, nobody in the carbon counting world has seen fit to research by how much. The modelers are estimating the carbon emissions of solar production as if the panels are still made mostly in the West, grossly underestimating their carbon intensity, even as governments rush to draft and implement net zero policy based on the very same flawed data.

A Lone And Obstinate Italian Data Crusader

The China-sized black hole at the heart of the world’s photovoltaic data might, in the context of the industry, seem obvious.

That didn’t make it any easier for Enrico Mariutti, an introspective but compulsive 37-year-old Italian from Rome, to convince others in the field there might be a problem. It was Mariutti who first made substantial efforts to flag the data discrepancies.

Like Greta Thunberg, Mariutti comes to the tale as an environmental obsessive passionate about facilitating the world’s transition from fossil fuels to cleaner forms of energy. Unlike Greta, Mariutti finished school and knows how to crunch through a data set. He holds a degree in geopolitics and global security, which, while unrelated to the field, has equipped him with enough quantitative skills to ensure he can recognize the difference between good and bad data.

Mariutti first noticed something wasn’t quite right with photovoltaic assessments about two years ago. He was preparing for an online renewables debate with Nicola Armaroli, a research director at the Italian Research Council. But being a data junkie, he decided to pour over the source material to try and figure out why. What he discovered unnerved him. The data didn’t reconcile.

"They [the data] showed how much solar photovoltaic systems used in terms of raw materials: silicon, aluminum, copper, glass, steel, and silver. Then I saw the carbon footprint. It just seemed way too small,” he told Environmental Progress.

According to his findings, the carbon intensity of solar panels manufactured in China and installed in European countries like Italy was off by an order of magnitude. An initial back-of-the-envelope calculation put it at between 170 and 250g of carbon dioxide per kilowatt hour (kWh), as opposed to the official estimate from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of 20-40g per kWh. Way off.

The scale of the IPCC’s undercount shocks once applied to the EU’s “clean” energy plans. Following Mariutti’s math, the esteemed scientific body underestimates the emissions from the EU’s solar installations built in 2022 alone by 5.4 to 7.6 million metric tons, equivalent to adding 3.4 to 4.8 million cars to the road.

By 2020, Mariutti felt compelled to make his findings public. He managed to publish an op-ed in Italy’s premier financial newspaper Il Sole. The piece argued it was wrong to describe an energy transition that depended on mineral-hungry tech, which “could double the exploitation of the earth’s resources within a few decades,” as a green revolution. It was a hit and went viral across Italian social media.

Enthused by what felt like a public mandate for his mission, Mariutti continued his research, firing off dozens of queries to the data compilers. Responses, however, were far from forthcoming. Until one day in November 2022, a leading Dutch renewables expert, Mariska de Wild-Scholten, replied.

Mariutti was delighted to have made an inroad. Wild-Scholten had been one of five key authors who had made significant contributions — she is named some 454 times — to the IEA report Life Cycle Inventories and Life Cycle Assessments of Photovoltaic Systems (2020) — a starting point for much government decision-making on net zero policy.

But what she told Mariutti was not reassuring.

De Wild-Scholten’s Secret Data Stash

In two emailed responses, Wild-Scholten said that, when determining the electricity consumption of silicon purification, which is used to make wafers, she rarely read scientific papers “because of low data quality, outdated data and or non-transparent data,” while saying little about her own preferred sources other than that it is based on surveys. Responses to other queries were no more reassuring.

Mariutti asked what she thought about 192 countries deciding their long-term energy strategy based on data that at the time reasonably underestimated the average carbon intensity of photovoltaic energy by one order of magnitude (40 vs. 250 gCO2/kWh). Her reply invited more questions than answers. “My experience is that nobody would like to pay for the data aggregation which is needed to come up with publicly available and free updates,” she said, adding that she was working on updating the public data “but only slowly.” Little to no indication was given for the source of her own data.

But, she said, she was happy to share the data she used to inform the 2020 IEA study — attaching it to the email — because it was now “outdated”. It was based on confidential individual company data, she said but did not specify the regional profile of those companies or any other aspects of their identity. She had kept it private only because she had not managed to get the studies funded.

By February 2023, Mariutti decided to self-publish his findings on his own website in a piece titled, “The dirty secret of the solar industry.” The piece made a bold claim: scientists were disingenuously using European data to model the carbon intensity of Chinese solar manufacturing. Was the goal here, he asked, to measure the carbon footprint of solar energy or merely to convince us that it’s green?

With a little prod from Mariutti, it was picked up in May in a piece by Giovanni Brussato for the Milan-based weekly Panorama. Brussato drew on Mariutti’s claim that one needs only to look at the life cycle analysis of China’s glass industry by the China Development and Reform Commission to see if there is a data reconciliation problem.

According to Chinese sources, it noted, glass manufacturing – another critical input in solar production – bears a carbon footprint of only 0.68 kgCO2e/Kg despite an admitted 70 percent dependence on coal-fired energy. A comparable study by Western researchers into the UK’s glass industry, which is mostly powered by cleaner natural gas energy, based on data from Eurostat and Guardian Europe, assessed the industry as having a carbon footprint of 1.12 KgCO2e/kg. To compare, the IEA scores solar between 0.5 and 1 kgCO2e/kg and Ecoinvent with 1 kgCO2e/kg.

A major issue with solar data, according to Mariutti, is that data compilers have been slow to recognize the displacement of the industry to China. It wasn’t until 2016, long after much PV production had already moved east, that the transition appeared on data collectors’ radars. But even then, they depended on new estimates and models rather than data from the source.

“In 2014, they calculated the carbon intensity of PV energy as if the panels were made in Europe, with low-carbon energy,” Mariutti told Environmental Progress, referring to data compilers. “By 2016, calculations started to appear as if the panels were made in China, i.e., supposedly with carbon-intensive energy.”

However, whatever model was used, the resulting carbon intensity was always around 20 to 40 gCO2/kWh. “Had they done the math right, it would come out at around 80 to 106 gCO2/kWh, and that’s with important factors still left out,” claims Mariutti.

After the publication of the Panorama piece, Mariutti’s claims drew the reaction of Dr. Marco Raugei, a leading researcher of emissions from renewable technologies at Oxford Brookes University, embroiling both in an extended online spat.

“We all used Chinese electricity mixes for c-Si PV. And we still got results nowhere near as high as you imply one would. So something is clearly off in your back-of-the-envelope calculations,” Raugei tweeted in April this year. By way of example, he cited an influential paper from 2021 on the sustainability of PV systems by life-cycle analysts Enrica Leccisi and Vsili Fthenakis.

Mariutti had previously critiqued Leccisi and Fthenakis’ analysis in his self-published piece, noting that while the electrical input of solar was modeled according to a Chinese scenario, thermal input remained European. After Mariutti pointed out to Raugei that he had tried to contact Leccisi for comment on his findings without success, the conversation with Raugei went cold.

In further correspondence with Environmental Progress, Dr. Raugei stressed that in his research, he endeavored to use the closest possible approximations to Chinese data in order to create a realistic scenario.

The Missing Chinese Data

When scientists, academics, or researchers lack accurate data in the Western world, they usually work hard to fill the data void directly. Major efforts are undertaken, and huge sums are spent on sourcing ever more reliable and better data.

Not so, however, with the China data anomaly. A lack of transparency, language barriers, and a plethora of inaccessible institutions – alongside a general reluctance by researchers to unearth realities that might dispel existing assumptions – have led to an overreliance on models and inputs extrapolated from Western manufacturing processes.

The IPCC’s own estimate that solar’s carbon intensity is four times that of wind and nuclear, but 10 times less than gas and 20 times less than coal is derived from such assumptions.

Unsurprisingly, the authors of the IPCC’s sixth assessment report, casually referred to as AR6, base their life cycle assessments (LCA) of solar energy on studies that do not represent the current state of the industry. Of the four studies cited by the authors, two evaluate only European manufacturing of solar panels. The third model is a state-of-the-art Chinese-manufactured panel, the Upgraded Metallurgical Grade Silicon (UMG-Si), which is no longer in production. The fourth reviews 16 studies, all of which either model solar panels that are no longer in production, model panels that make up only a few percentage points of the global market, or employ Ecoinvent’s 1 or 2 inventories, which also use European electricity mixes.

Ecoinvent, the omnipresent database that is relied upon by policymakers and academics across the planet, as well as manufacturers, big and small, was founded by Dr. Rolf Frischknecht.

For over 20 years, his Swiss non-profit, funded at least in part by the Swiss government and the photovoltaic industry, has collected data on the environmental impact of renewable energies. Whether you’re modeling the low-carbon appeal of recycled plastic packaging, automotive filters, or titanium powder, Ecoinvent is the likely source of the data. A recently agreed collaboration on zero-carbon shipping with major players in that industry showcases the association’s still-growing influence.

Since the early 90s, the reputation of Dr. Frischknecht has grown in step with the renewables industry. Some 20 years ago, he began a collaboration with the IEA through the Photovoltaics Power Systems Programme (PVPS), a joint initiative from the IEA and the global PV industry to conduct research on solar and turn it into a global energy “cornerstone”.

Despite his careful stewardship of Ecoinvent, in 2021, Frischknecht quietly resigned from the body he had founded decades earlier. In his resignation letter he noted “irreconcilably different perceptions regarding materiality, reality, quality and accountability” of their latest data.

“There was a drastic shift from (appropriate) data to methodology,” Frischknecht wrote to Environmental Progress. Faced with a movement away from real-world data collection, discussion of what were the crucial data points, proper referencing, and extensive data quality checks, as he had explained in his resignation letter, Frischknecht felt obliged to move on. “During my career, I tried, and try, to be independent of direct, indirect, and subtle attempts to influence the modeling or the data,” he told Environmental Progress.

He then cast doubt on the quality of the Ecoinvent data, telling Environmental Progress, “The PV data in Ecoinvent is from 2011, and there is no data from Chinese information sources.” In email correspondence with Ecoinvent, Environmental Progress was able to confirm Frischknecht’s allegation.

Frischknecht now runs Treeze, a “young and experienced” life cycle assessment consultancy, which is “involved in large EU projects”. Treeze also receives funding from the Swiss Federal Office of Energy and collects life cycle data for the PVPS “Task 12” report on solar’s sustainability.

The total lack of Chinese input into Ecoinvent’s data, however, has not stopped the IEA from continuing to depend on the potentially outdated work of Frischknecht’s brainchild for their own estimates.

These revelations undermine the foundations of the sustainability industry, which bases a significant portion of its certifications on Ecoinvent’s data and promises businesses and governments that earning their certifications protects the planet.

The sector has ample reason to trust Ecoinvent without checking its data. The sustainability sector makes billions of dollars each year thanks to the scale of carbon reductions they claim to provide, and disclosing that it failed to deliver its most basic pledges threatens its business.

Read the rest here...