By Peter Tchir of Academy Securities

Jobs and AI

This isn’t about jobs that will be displaced by AI, or jobs that will be created by AI. It is a look at the job market today, the data, and some questions regarding AI on that subject. On Friday, we did a quick post-NFP Report – Look Out Above on Yields. It focused on how the strong data (and the NFP report was quite strong), coupled with growing concerns about the inability to force inflation lower, will keep the Fed on hold. But, as the day went on, after multiple conversations on the market reaction, and while preparing for some presentations next week, I couldn’t get one thought out of my mind:

What if markets reacted so poorly because no one believes the data, but everyone believes that the Fed will need to react to the data?

It is a simplification. It likely overstates that sentiment, but I think that there is something to it, so we will explore. This will lead us to some questions, and maybe some answers, but definitely some questions about AI.

Geopolitical Outlook 2025

If you missed Geopolitical Risks & Opportunities from Tuesday, I highly recommend giving it a quick read. We focus as much on the opportunities as the risks. With geopolitical risk at or near the top of everyone’s list of concerns for 2025, it seemed appropriate to highlight the opportunities. Being too pessimistic about risks might cause you to miss them. Yes, there is an irony about the T-Report warning you about being too pessimistic, but there you have it.

We cover a range of topics beyond the usual suspects. Space and Cyber get some treatment through a national security lens. Shipping is an area where we were possibly at risk of being labeled “the boy who cried wolf,” but it is garnering longer conversations. “BRICS and Barter” is highly relevant as we expect to see some tariff and trade activity via executive order in the early days of Trump 2.0. Peace through Strength is an overriding theme, though not sure how Canada, Panama, Mexico, and Greenland feel about that.

Back to Jobs

After that brief geopolitical detour, let’s get back to the task at hand: understanding the jobs data.

Bloomberg had estimates from 75 economists. This is not just a “handful” of estimates. It is a pretty robust sample size. All the big-name firms were in with their estimates. Some of the best independent firms were included in the survey. Bloomberg even takes the time to tabulate who the top 10 are at estimating the number (presumably using track records from prior estimates).

This group of highly intelligent, motivated, and typically well-resourced survey respondents had an estimate of 165k for jobs. The top 10 did better (if better means getting closer to the published number) with an average of 186k. I often like to examine the most recent submissions (under the premise that they incorporate the latest data and therefore might be making more of an effort). 16 estimates were provided in the 2 days before the release and they averaged 174k, so a bit better (again, assuming coming closer to the published number is better), but still off.

There was exactly 1 estimate higher than the published number. The Bloomberg Economics estimate is ranked 6th and was submitted 2 days before the release. There is some method to the madness of trying to qualitatively analyze the estimates.

A whopping 98.7% of analysts had estimates below the official number.

Not only were 74 out of 75 below the official data, but also only 5% of the estimates were above 200k. Think what you will about the dismal science, but I find it incredibly difficult to believe that so many really smart, organized, well-resourced, and well-intentioned estimates were all so wrong.

It almost defies explanation that this many people could be so wrong – which gives rise, at least to me, that potentially the published number itself is inaccurate.

ADP, which presumably has some good, real-time, real-world data, had a miss with only 126k jobs. Far fewer economists bother to estimate ADP, but the distribution looks far more normal with some a little high, some a little low, and a couple of outliers. This is a distribution of estimates that does not indicate gross incompetence. This is one takeaway (a cruel takeaway, and clearly not one that I believe in) from the NFP estimates.

Some “Silly” T-Report Items

In Messy, But Manageable, we highlighted two recurring thoughts on jobs data:

1. Expect a strong Household Report because it was so bad recently relative to the Establishment Report (check the box on that one).

2. The seasonal adjustments are off and add too many jobs every winter (including data during COVID and due to missing the shift in where construction occurs). We don’t know if we were correct on this assumption, but if we get downward revisions later in the year, we might try taking a small victory lap.

These were two basic reasons why we thought we could see better than expected data. In that report, we highlighted that the “whisper” number was even lower than the official estimates (which might also explain the market reaction).

We have written a lot about problems with the jobs reports over the years that go far beyond these simple issues. We’ve covered what we believe are flaws in how the Birth/Death model works in a “gig” economy, the low initial survey response rates, etc. Others are harping on these issues more and more.

Which brings us back to where we started today’s piece.

What if markets reacted so poorly because no one believes the data, but everyone believes that the Fed will need to react to the data?

While not today’s topic, we’ve had similar discussions about inflation. It was so clear (to anyone who actually had to buy anything) that the official inflation data wasn’t capturing the extent of inflation in the real world. The “owners’ equivalent rent” was so far behind anything remotely representing timely transactions in the rent market, that it would have been laughable if it didn’t seem to shape Fed policy.

The Fed is forced to rely on official data (hard not to given that it is an honest effort, and all that the mainstream media focuses on), but the data isn’t reflective of reality. Does that lead to policy mistakes?

I’m not saying that is occurring, but I am saying that when 99% of people get something “wrong” maybe we should rethink the number itself and not their estimates.

Instead of trying to evaluate if they did “better” in terms of guessing the actual number, we should be wondering if the number itself should be questioned. Ahhhh…now we can see where AI might come in handy.

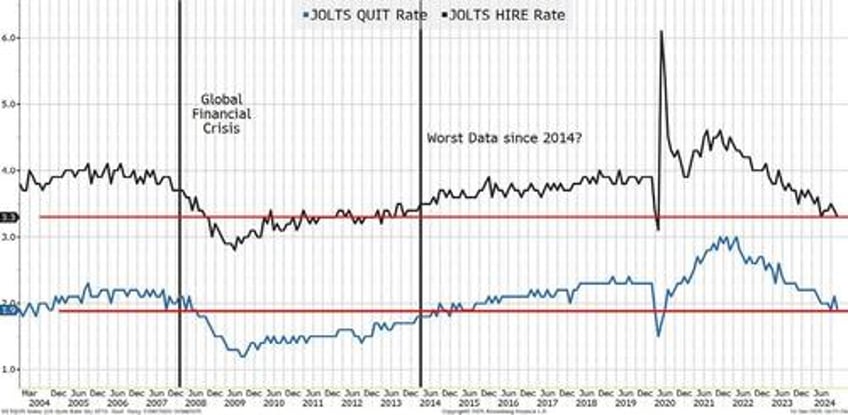

One Jobs Chart

It would seem cruel to rant and rave about the “official” data possibly being wrong without providing at least one chart.

I’ve been arguing (I think rationally, some might say hysterically) that the JOLTS Job Openings report is another one where the official data hasn’t caught up to how jobs are really advertised. The number of jobs available “coincidentally” seems much higher since on-line sites are now the primary tool for job searches. I am confident that it is not a coincidence, and that we aren’t accounting for how those platforms are used, hence the overstatement of jobs. But enough on that, I do think that the Hire and Quit rates are at least somewhat useful, particularly the Quit rate.

We have argued that the QUIT rate is the closest thing that we have to “crowd sourced” data. People who decide to quit (or not quit) have a lot of information about their job prospects. They know themselves, their fields, and the current state of hiring in their fields. Presumably, they have a sense of geographic hot spots and their willingness to move there if necessary. A QUIT rate below 2% is something that we really only saw as we entered and slowly recovered from the GFC!

I’m aware of the issues with identifying a couple of pieces of data (in a slew of data that I generally think is off), but I’m willing to live with that paradox. Also, in a similar vein, it is impossible not to point out that the HIRE rate is pretty abysmal too.

AI and Jobs

Could AI help get better jobs data? Presumably having good information (accurate and timely) on the labor market would be good for policy makers and decision makers at every level.

As we ask that question, we probably need to assume that even if the BLS doesn’t use AI (and they might well use it), at least some of the survey respondents incorporate some amount of AI into their analysis.

Let’s just for a moment assume that someone develops an AI-based tool that accurately analyzes the job market. Whatever this AI-based model spits out is the reality of the job market. Would it help or hurt you if it didn’t match the official data?

From a trading perspective, over the short-term, I’m not sure how much help it would be to “know” the reality if everyone is going to trade off of the other number. Presumably over time, investors and corporations would benefit from having the actual data, even if policy is based on the potentially erroneous official data. Or would you just make “different” mistakes because policy doesn’t match what you prepared for? You would like to think that it has to help, but when we see downward revisions of a million jobs from the previous year, the market tends to shrug its proverbial shoulders. Is the dirty little secret that no one wants to go back and admit that decision after decision was made on bad data? Basically, admitting to garbage in, garbage out.

I have no idea what the answer really is, but now I feel justified in not trying to build an AI system to calculate the real state of the job market since it wouldn’t help me anyways. Clearly, somewhat tongue in cheek, but makes you think, I hope.

The corollary of this is if this jobs data is incorrect and will later be revised, but it is an input into your AI, are you getting useful answers?

Applying more AI to the BLS process might be good. But it doesn’t fix things like the survey response rate. It just would attempt to potentially use it differently. Presumably “better” but how would we really know?

If you thought this section on applying AI to jobs would be easy, you probably know more than I do about AI, but I cannot help but think it highlights two issues:

- If you get an “answer” that people in charge don’t agree with, what did you accomplish (this seems like a second order effect, that some, but not all, can overcome).

- If the “answer” is based on bad data, what good is it?

I’m nervous that all I’m doing is exposing my still very limited understanding of AI, especially since it doesn’t correlate well with the massive rush we’ve seen to apply it to more and more questions using more and more data. Maybe the data and questions are valid, but I cannot help but wonder.

Bottom Line

Messy remains a theme. On rates, the 10-year at 4.76% seems like a screaming buy in my head and in my gut, but I cannot get there. I remain nervous for now and think that we proceed towards 5%.

Equities will be choppy and will be negatively affected by higher yields, but the driving force will ultimately be understanding what policies Trump 2.0 prioritizes and how likely those policies are to get implemented.

Credit supply will remain heavy, but spreads will remain well behaved.

I started the report thinking that AI and Jobs were a perfect match, but now I’m less sure. Alternatively, I didn’t think that I’d agree as strongly with the view that the risk of making policy decisions on bad data is not only real, but it is also possibly starting to get priced into the market!

Per the Philadelphia Fed, average monthly jobs growth was 130K in 2023. Biden's Dept of Labor reported that this number is 230K. That's a 100K difference that led the Fed on to believe the economy is far stronger than it was.

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 20, 2024

Tomorrow the BLS will reveal its own revised data. pic.twitter.com/S9MkEH8oMI

Alternatively, the official data might be accurate, and we might all be really bad at predicting it, and I’ve wasted your time with this report (though I highly suspect that is not the case).

With wildfires and devastation raging in California it is extremely difficult to find a positive way to sign off today’s missive.