By Masaki Kondo, Bloomberg markets live reporter and strategist.

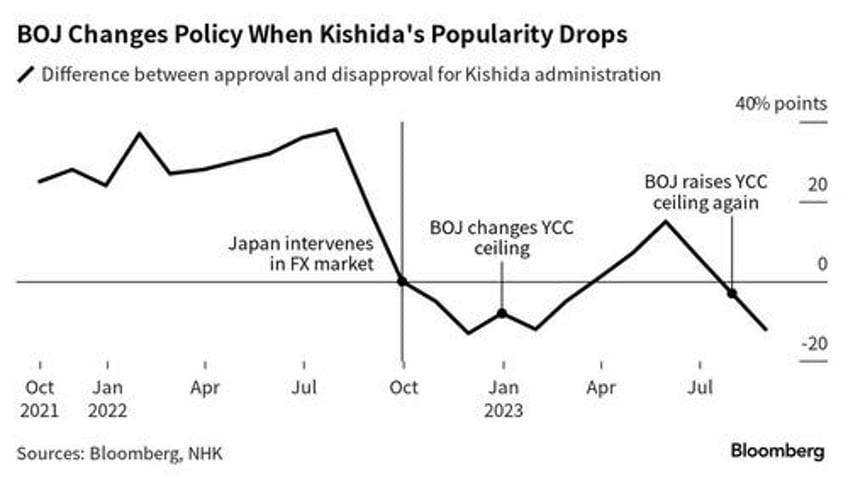

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s falling popularity adds to the risk that the Bank of Japan may surprise investors again with a policy shift that will make voters happier.

Political distress has emerged as a potential leading indicator for action in monetary and currency affairs since late 2022

When Japan intervened to prop up the yen in October, it wasn’t just the currency that was falling — Kishida’s administration’s approval rating was also plumbing new lows.

The blowback against the Japanese Lira begins.

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 29, 2023

Let's see how long Kishida allows the BOJ to cremate the JPY once Japan's plummeting standard of living and his approval rating starts correlating to the yen pic.twitter.com/qcKAgvXukz

The government was drawing fire in opinion polls again in December, when the central bank unexpectedly raised the ceiling for yield-curve control. And when the BOJ caught investors off guard once more in July with a further adjustment to YCC, the PM’s popularity was yet again on the slide.

This isn’t to deny that underlying economic and market pressures are the fundamental drivers of monetary and currency policy. Nobody is suggesting that the government directs the central bank, which has its independence enshrined in law.

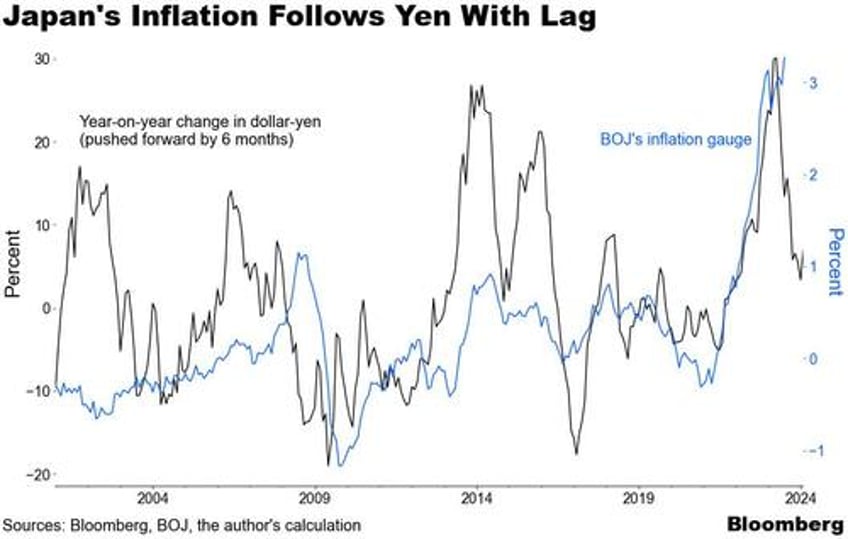

Yet there is a clear line that connects the weak yen to inflation, and inflation to unhappy voters. When it comes to the timing of actions that can take some of the sting out of inflation, recent history indicates opinion polls are at least worth watching.

It may also pay to keep an eye on the periodic meetings between Kishida and the BOJ governor. Many traders can probably recount that the then-Governor Haruhiko Kuroda raised concern over the yen when he met the prime minister about a month before raising the YCC ceiling in December.

Kazuo Ueda, who was chosen by Kishida to succeed Kuroda earlier this year, has also shown himself to be highly attuned to the plight of the yen. Ueda surprised BOJ watchers in July when he acknowledged that foreign-exchange volatility had been a factor in raising the YCC cap again.

The most recent public record of a meeting between the pair is Aug. 22, when they discussed financial conditions ahead of the gathering of global central bankers in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

That said, Kishida’s problems with voters go way beyond areas the BOJ can influence, even if he could bend the central bank to his will. The sources of dissatisfaction with the government range from a national ID card, to the country’s low birth rate, to the handling of waste water from the Fukushima nuclear plant.

But maybe all these caveats are immaterial. The link between the yen and inflation, and what this means to the government and the BOJ, is clear to see. Keeping tabs on opinion polls may be prudent until someone can show that they don’t matter.