An unusual combination of divergences in the stock-market volatility space suggests the VIX is at elevated risk of pricing higher, and this may even happen with rising rather than falling equity prices. Volatility of volatility is near 10-year lows making call options on the VIX cheap.

Buying the VIX is the quintessential widow-maker trade. It is rare for the gauge to rise, with most of such instances over the last 20 years episodic and occurring when the market was falling. Most of the time, the market rises and volatility falls - there is an entire sub-industry devoted to exploiting and perpetuating this, which has swollen further in size in recent years with the boom in zero-days-to-expiry (0DTE) trading.

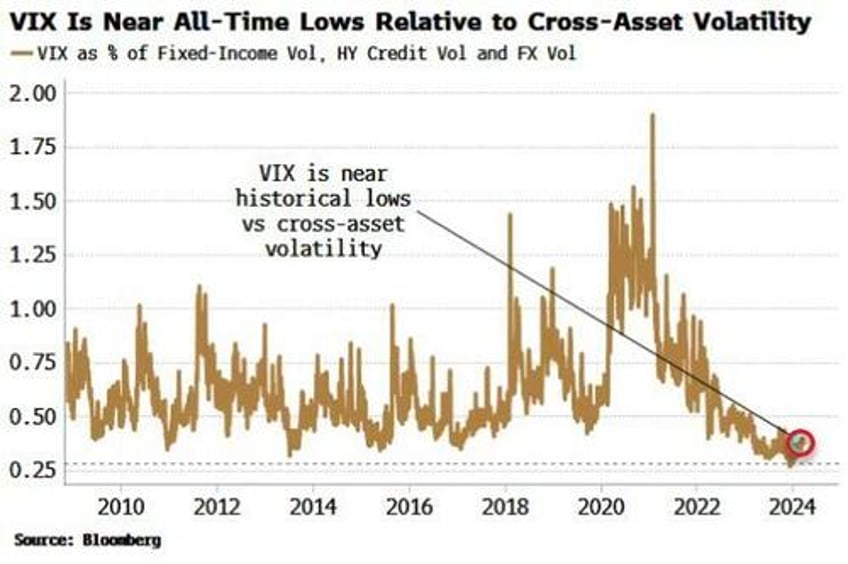

Not only is the VIX near its post-pandemic lows, it has also never been more out of step with cross-asset volatility – FX, fixed-income and credit (which is saying something as FX and credit vol are themselves near historic lows).

Markets are interlinked: rates impact stock valuations, high-yield credit sits just above equity in the capital structure, and so on. The question is how long can equity volatility remain the relative outlier?

There’s always a risk of becoming the next widow, but there are enough factors in play to suggest a heightened risk of a rise in the VIX.

Three trends suggest that a turning point in equity volatility is near:

Divergence between the VIX and skew structure;

Implied and realized correlation nearing their effective lower bound; and

Stresses in state-by-state US unemployment.

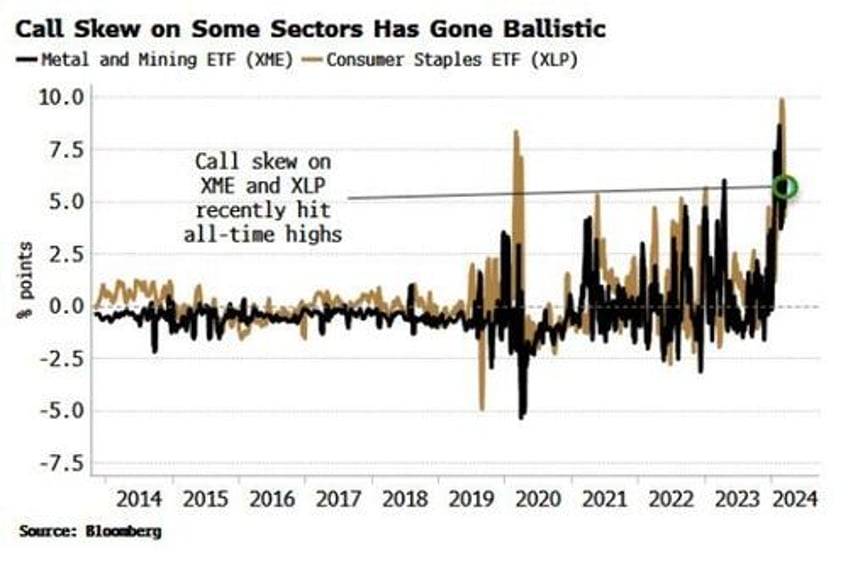

The market has become increasingly bullish in recent months, especially so after making new highs. That’s led to leveraged market chasing – call buying – and reduced hedging activity, i.e. less put buying. The rally chasing spurred some truly epic moves in the call skew of certain sectors. The metals and mining and staples sectors saw the biggest rises in their call skews, with both hitting series highs.

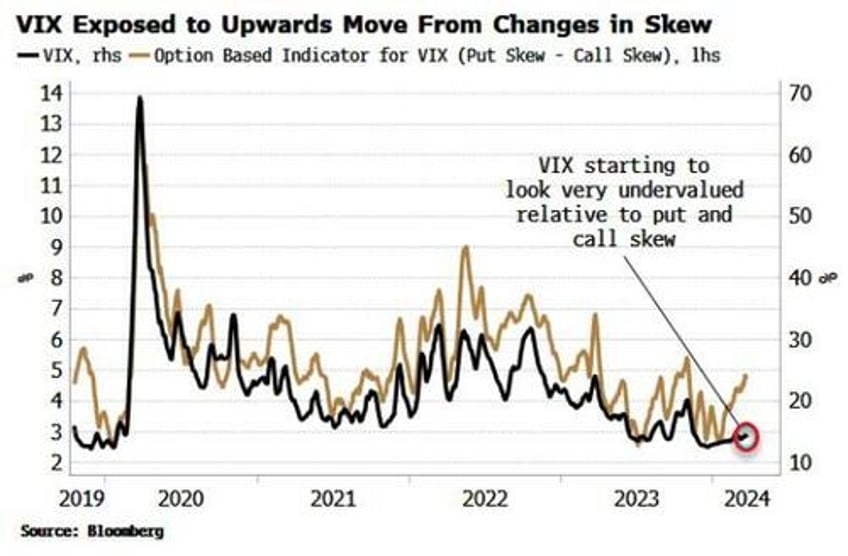

However, since 2020, it’s the relationship between call and put skew that’s tracked the VIX almost perfectly, with the index typically falling when call skew is outpacing put skew. In other words, when there is more leveraged activity in calls relative to puts, the VIX tends to be repressed (the VIX is a weighted-average of implied volatility in the S&P across all strikes).

Now, though, put skew is outperforming call skew. As the chart above shows, that typically coincides with a rising VIX.

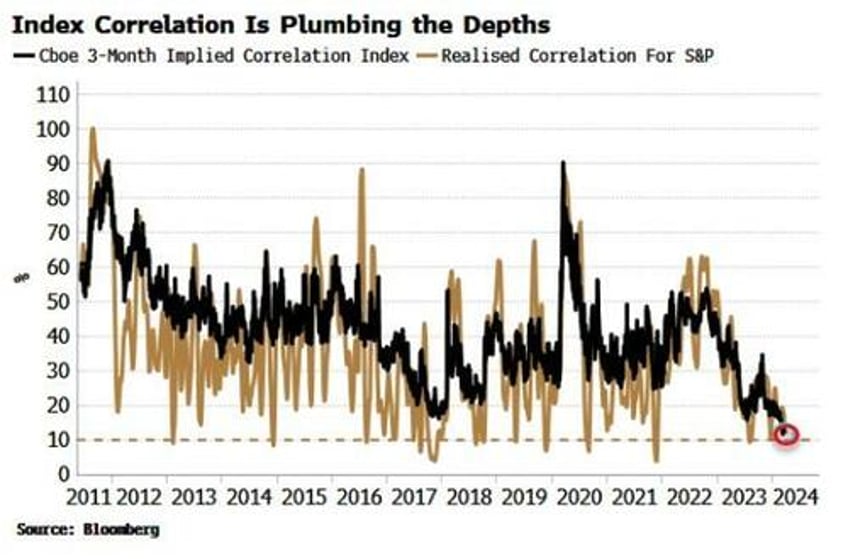

At the same time, the realized and implied correlation of the S&P is very depressed. Realized correlation is close to going below 10%, a level it rarely breaches, and when it does it is typically followed by a sharp move higher. Moreover, implied correlation - so called as it is implied from the Markowitz portfolio model - has never been lower.

Correlation is being driven lower by the dominance of the largest stocks and by dispersion selling. The latter involves selling volatility on the index versus buying vol on individual stocks. As the Magnificent Seven - or whatever your favored cohort of AI-related stocks is - drive higher, the dispersion selling has the effect of pinning the index. The biggest stocks go up, while the rest are impaired by how much they can move, pushing correlation down.

In theory, index correlation could go negative, but it has never happened. The reason is that stocks are not completely random and are driven by common macro-based factors, such as interest rates. Correlation is thus so low today that it can only really go one way, and when it does, history shows the move is likely to be abrupt. Something has to give.

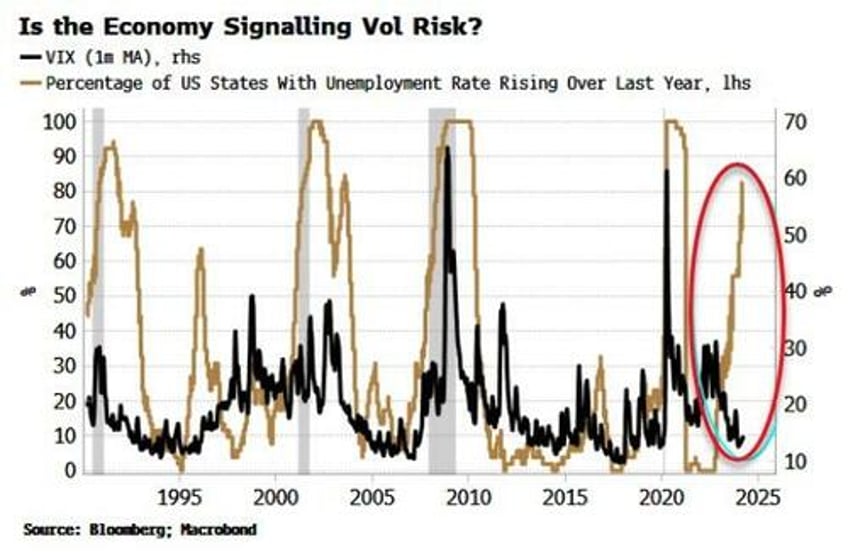

It’s not only the market sounding a warning about stock-market vol, but the economy too. A fairly reliable indication of rising equity volatility has been when we see a number of US states experiencing stress in their employment markets at the same time.

The chart below shows the percentage of US states whose unemployment rate is higher over the past year. As we can see, while increases in equity vol don’t always coincide with rising state unemployment, almost all the spikes higher in the percentage of states experiencing worsening unemployment coincide with episodes of higher VIX.

Today is - so far, along with the mid 1990s - an outlier, with more than half of US states seeing rising unemployment while the VIX remains near its lows.

There is a proviso here. The household survey, from which the unemployment rate is derived, may be under-reporting employment growth due to underestimating immigration. A recent Brookings paper suggests that the household survey is using too low an estimate for the civilian population, which could well explain its divergence from the establishment survey (payrolls). It might also bias state unemployment rates too high if estimates of the size of the workforce are too low.

Nonetheless, this measure bears close scrutiny, especially in confluence with the endogenous market-based signs of higher equity vol mentioned above.

Being long volatility is rarely comfortable. Given the structure of the market, the path of least resistance is down. This also means the volatility curve is typically steep – as it is today – meaning an investor wears negative carry to hold the position. One way to mitigate this is through call options on the VIX. These are relatively cheap, with the VVIX – the vol of vol – near 10-year lows.

The reflex is to expect higher equity vol to come with lower stock prices. But the two had a positive correlation for much of the second half of the 1990s. The current backdrop of still-supportive liquidity, a non-recessionary economy and investor call buying could lead to a situation of rising volatility and higher equity prices. That might make long volatility trades a less likely money-losing proposition.