Macro-economic factors - not earnings, revenues or margins - are the primary driver of global stock markets over the medium term. The macro outlook for stocks is supportive for now, but that’s likely to be short-lived.

Does macro matter?

Renowned investor Peter Lynch thought it a waste of time: “If you spend 13 minutes a year on economics, you’ve wasted 10 minutes.” Focus on business growth, not GDP growth, he implored.

In the years leading up to the GFC, whether macro is important was an inauspicious question I was asked regularly by prospective clients of my former firm, a macro-economic consultancy. After the tumult of the last decade and a half, I hear it less often, but it’s not gone away.

Does macro still matter, then, if you are a stock investor? The answer - unless you have an investment horizon of well over a year with no liquidity constraints - is a resounding yes.

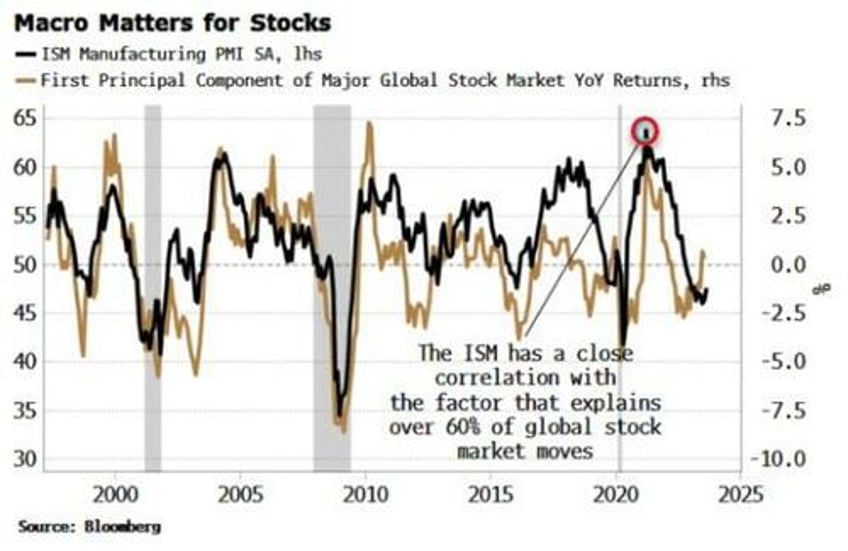

To see why, we need to identify the main driver of global stock-market returns. This we do by using a statistical tool called principal component analysis (PCA).

As a quick example, say you were trying to ascertain which features best explain the lifespan of mammals. You might measure their height, weight, average heart rate, and so on. PCA will tell you which input – or combination of inputs – has the greatest explanatory power in determining the average lifespan of different types of mammals.

Applying PCA to global stock-market returns yields a very interesting result.

It shows that over 60% of global stock-market moves is described by just one factor. But what’s even more noteworthy is that this factor (called the first principal component), is highly correlated to the US’s ISM manufacturing index.

This is a remarkable result.

Stocks over the medium term are not in the main explained by more obvious variables endogenous to the market, such as global earnings, revenues and profit margins, or the dollar or global yields, but by survey-based expectations of the outlook for US manufacturing, a sector making up only ~11% of the country’s GDP.

Why is this?

There are two main reasons:

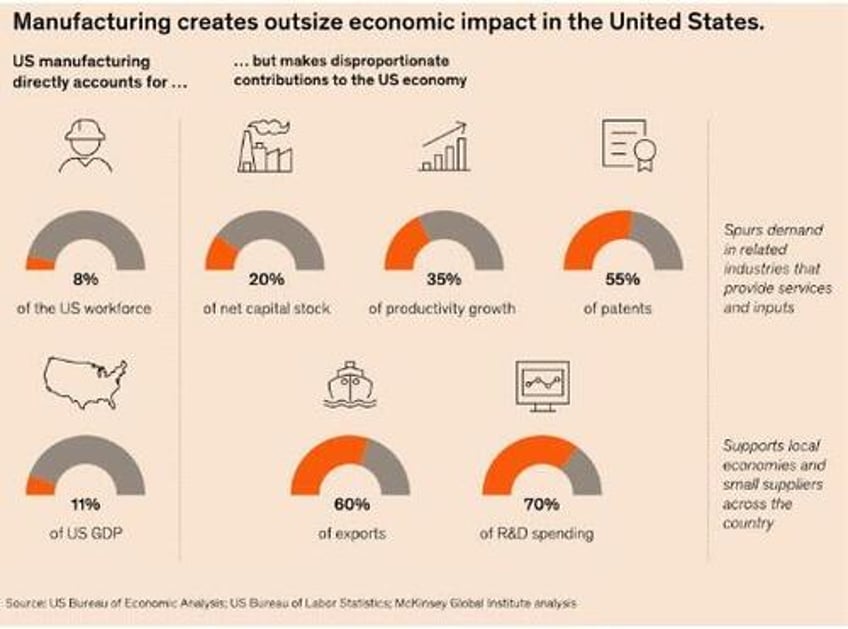

manufacturing in the US punches well above its weight in several ways, despite only accounting for a small proportion of GDP;

and its sensitivity to interest rates means it typically leads the ups and downs of the rest of the economy.

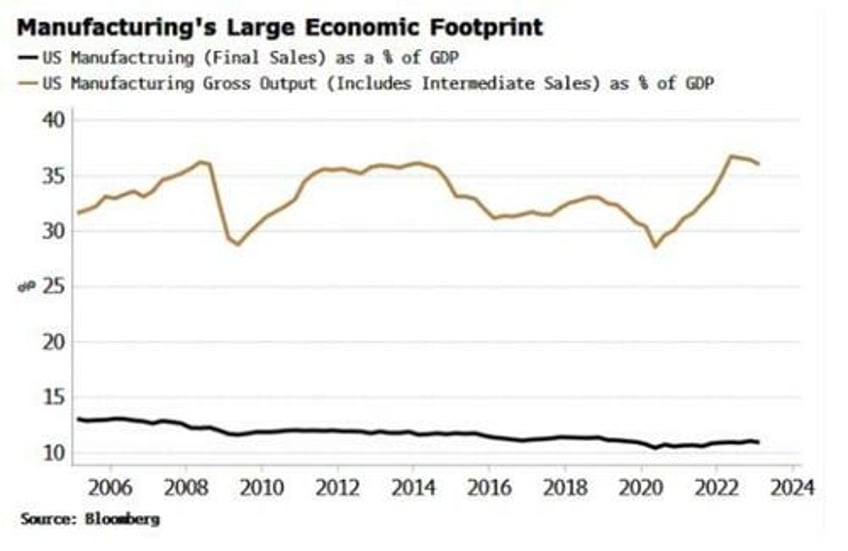

GDP measures only final value-added, and not intermediate inputs. Manufacturing is responsible for a large volume of sales to non-final users who are not counted as part of GDP. This measure is called gross output. Despite manufacturing accounting for only a little over a tenth of US GDP, in gross output terms it supports over a third of economic activity.

A heavy reliance on other inputs such as energy and construction as well as many services means manufacturing creates disproportionate demand. Furthermore, it has an out-of-proportion impact on employment, with manufacturing jobs supporting many jobs elsewhere in the economy.

On top of that, according to McKinsey, manufacturing is also responsible for 55% of patents, 60% of exports and 70% of R&D spending in the US. The old economy still has huge clout.

Source: McKinsey

Manufacturing is also typically an early-warning signal for broad economic weakness given its high sensitivity to interest rates. The cost of borrowing to invest and the cost of credit – crucial for customers to buy manufacturers’ big-ticket goods – both increase when rates rise.

There is a note of caution required here.

The usual caveat that correlation is not causation applies. Further, rarely if ever are market and economic relationships monocausal or without feedback effects. The strong correlation between the ISM and the global stock-market factor is also likely explained by the impact of stock prices on the ISM survey. Purchasing managers’ general perception about the economy, and their own businesses, is highly likely to be colored by the recent performance of the stock market.

Nonetheless, US manufacturing’s significant economic footprint domestically and across the world means there are compelling reasons why the ISM should explain so much of global stock-market returns.

Where does this leave us today? One of the best short-term (~1-3 months) leading indicators for the ISM is the ratio of the survey’s new orders and inventory components. This has been turning up, suggesting the ISM, and therefore global stocks, should hold up in the near term.

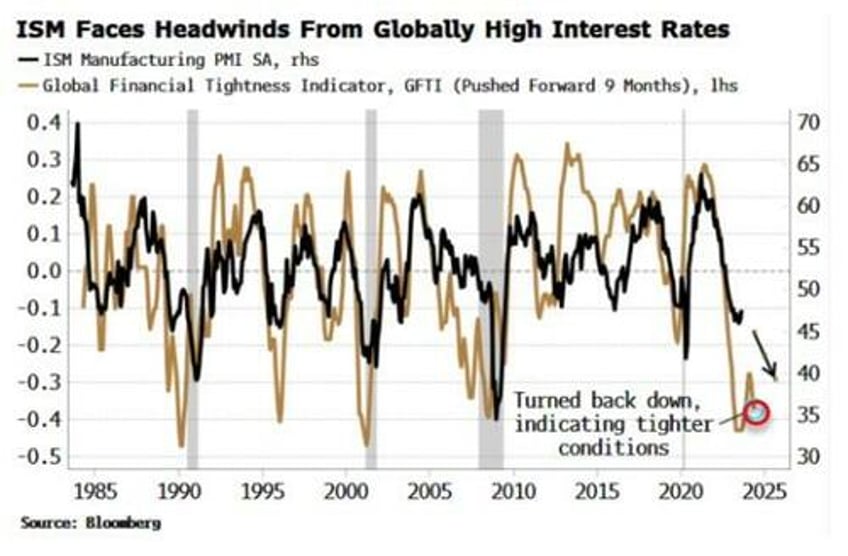

But it’s not fated to last too long.

Global interest rates have risen sharply over the last two years, and the full effects have yet to be felt.

The chart below shows that the Global Financial Tightness Indicator – a diffusion indicator of global policy rates – anticipates weakness in the ISM over the next ~3-9 months.

While the hyper-excitable stock market is prone to periodically getting carried away by the next New Thing, AI being the latest cause for breathlessness, macro and the old economy have not gone away, and they remain as important for returns as ever.