Submitted by Eric Hickman of Lantern Capital

The strong jobs report today (+254k) caused the dam to break on what I’ve been writing about for weeks with Treasury yields. The 2-year yield is higher by 22 basis points today. With the 2-year now at 3.93%, the bond market is priced for the Fed to cut rates to 3.25% by March of 2026. This would be a 25-basis point cut at 7.5 of the 12 meetings in between now and then. This seems like fair pricing for the conditions given the Fed’s desire to slowly get rates back to neutral.

But I’ve never seen a big pop like this be limited to just one day. I expect yields to continue rising for a while (particularly at the front-end of the yield curve) until negative economic data reasserts itself. The narrative from Austan Goolsbee, president of the Chicago Fed, and Jerome Powell is that the Fed is going to cut rates back to neutral (somewhere around 3%) with or without economic weakness. But Fed hawks are going to quickly worry about inflation after today and try to un-do the favorable financial conditions (low Treasury yields). For instance, Larry Summers said today that cutting 50 basis-points was a mistake. It wasn’t given the regularity of the business cycle, but he is a good barometer for the hawkish side of the Fed. I expect for some member of the FOMC to say a version of “don’t count on us cutting back to neutral.” If this is said, the 2-year will become un-moored. The jobs number today represents a narrative change, and it is a process to work through before rates fall again in this Treasury bull market.

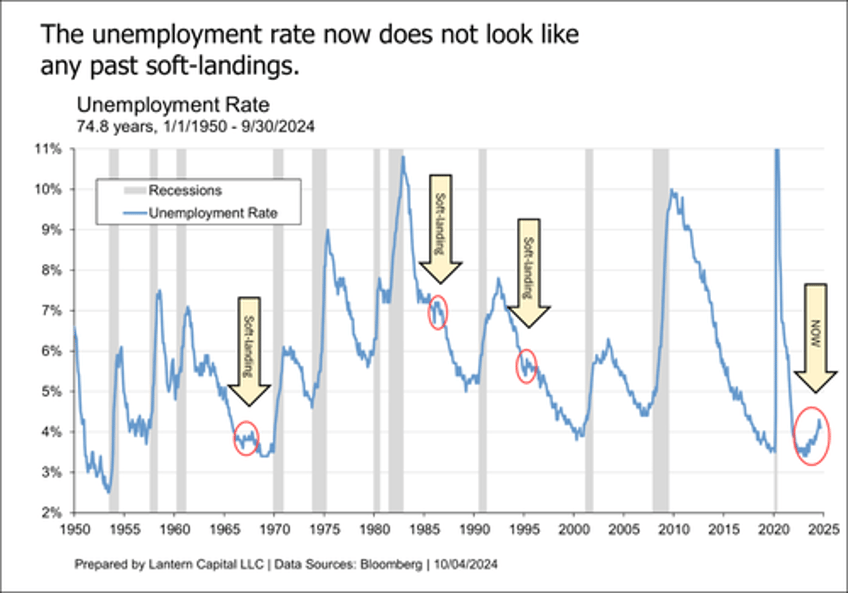

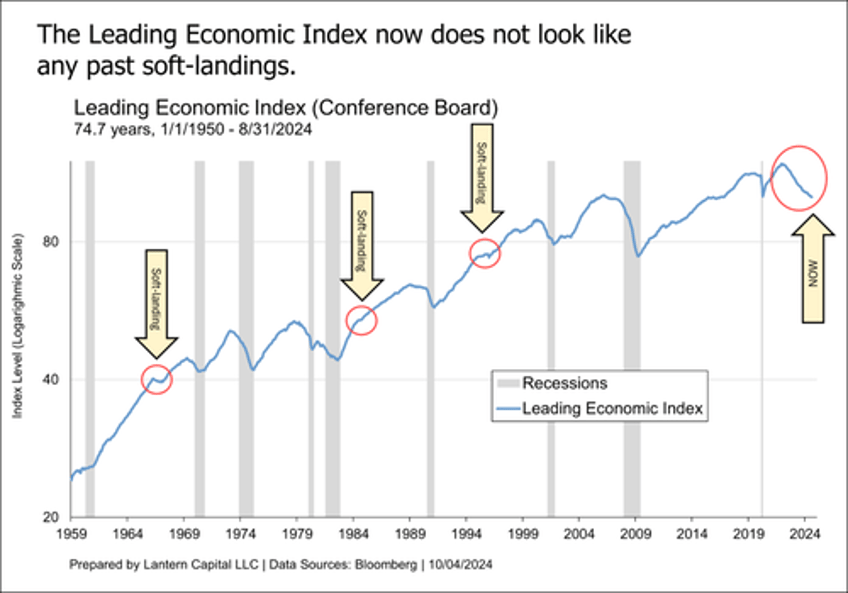

But today’s economic data doesn’t change my expectation of a recession one bit; it just suggests it is further away until more negative economic data comes along. The preconditions are set and make economic sense. The inverted yield curve, the unemployment rate rising, and Leading Economic Index have all signaled a recession is coming. Historically, if two of these signal, a recession occurs. In this cycle, all three have signaled. See this image for further detail. Soft-landings have one or none of these conditions and are pretty evident in the charts below.

The arguments against this are that a recession hasn’t come yet, the Fed is going to lower rates before one comes, and that there are no economic imbalances to correct. Responding to the first, a recession has likely been delayed because of large fiscal deficits. The U.S. deficit to GDP in 2023 was 6.3%. The European Union, that began to cut rates the earliest of the G-7 in June, had a much-lower deficit to GDP of 3.6% in 2023. The UK, that began to cut rates in August, had a deficit of 4.4% of GDP in 2023. This correlation is too simplistic, but the point is that deficit spending buys temporary GDP growth and the U.S. has spent the most among the G-7, likely delaying the business cycle.

Second, the Fed is not going to be able to cut blindly down to neutral (around 3%). Inflation is a concern every step of the way and the reason why the Fed can never get ahead of the business cycle. Today is a good example with Larry Summers’ comments. The Fed needs to see escalating economic weakness as they cut to make them feel comfortable about inflation. I wrote more about this here.

In response to the third, risk-markets (i.e., the stock market) are the imbalance. The S&P 500 has returned 16.9% annualized (total return, dividends re-invested) since the Great Financial Crisis low on March 6th, 2009. It isn’t unusual for the stock market to go through 9-18 year periods with high returns like this, but it has been 15.5 years so far and with the labor market deteriorating, I think a recession is going to start a long period of mean reversion. See chart here.

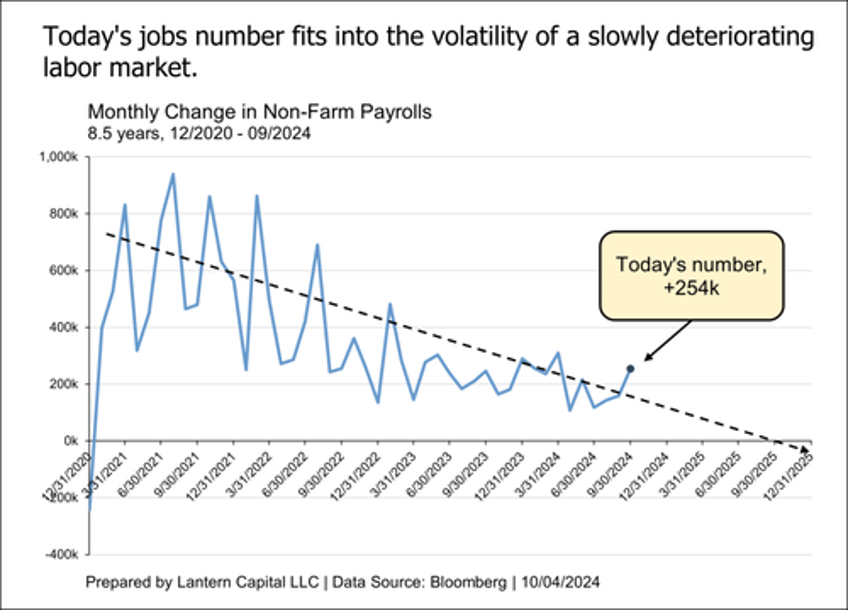

Today’s jobs number fits into the volatility of a slowly deteriorating labor market and there are plenty of examples of big jobs numbers before recessions. Looking at initially reported data (not revised), non-farm payrolls were +372k in February 1990, six-months before that recession began. Payrolls were +268k in January 2001, two months before that recession began. And payrolls were +166k in October of 2007, two months before the Great Recession began. See chart below.

It is hard to find someone that doesn’t think this cycle will result in a soft-landing, but the time-tested signals are very clear about the opposite and the incentives to be optimistic among nearly everyone build-up the soft-landing theme into a bigger thing than it is. In a telling part of Jerome Powell’s interview with the President of the NABE (National Association of Business Economics), Ellen Zentner on Monday, Jerome Powell wouldn’t acknowledge a soft-landing,

ZENTNER: Do you think that the 50 basis points you delivered in September. That cut, you described as a strong start. Did that cut give you more confidence in a soft landing?

POWELL: [4-second pause] I would put it this way. It is a reflection of our confidence that inflation is moving sustainably down. Or, our growing confidence that it is moving sustainably down to 2%. You know, as I mentioned, our design overall is to achieve disinflation down to 2% without the kind of painful increase in unemployment that is often associated with disinflation processes. That’s been our goal all along. We’ve made progress towards it. We haven’t completed that task. I think you’ll see us using our tools in a way that shows our commitment to achieving that. I don’t want to make a judgement about its likelihood, I just want you to know that we are committed to using our tools to do everything we can to achieve that outcome.

ZENTNER : Well you know economists everyday are asked for a probability of a soft-landing. I try very artfully to avoid it, but I just have high hopes.

Think of how easy it would’ve been for him to say “yes” if he felt that way. Ellen Zentner’s response is a perfect encapsulation of how business economists feel, they try to be optimistic despite what they may see. Not only do I see a recession coming, but I’ve yet to see a credible reason why it wouldn’t. Today’s jobs number has nothing to do with it.