Stocks are becoming expensive, but in real terms they could get much richer before becoming historically overvalued relative to bonds.

Driving while using only the rear-view mirror is not advisable. Yet in market analysis we are forced to do just that frequently. Nowhere is that more true in one of the most lagging of economic variables – inflation. It tells you the change in prices that has already happened, and says nothing about the future.

On top of that, inflation is not a clearly defined concept. Even restricting ourselves to consumer inflation, there is an enormous amount of subjectivity in how one defines the consumer basket, and the inflation that each person experiences is likely to be different from the official measure, and from everyone else too.

All of which means the concept of real yields requires a bit more thought. Commonly they are deflated using consumer inflation, using either the headline number or breakevens. Setting aside whether consumer prices are the correct measure to use, we are still faced with a central inconsistency: inflation is backward-looking, yields are forward-looking.

If a real market variable is to be useful, it should tell us what we think people will do. A real yield of say -2% is based on where inflation was. But if inflation was expected to be high in the coming year, then this means a much lower expected real yield. That gives us a read on how investors are anticipated to behave on a forward-looking basis.

Colleague Cameron Crise recently did some interesting analysis on real yields and the equity risk premium. Recent experience might inform you that as real yields rise, that is negative for equity valuations relative to bonds.

But as he showed, this is only a post-GFC phenomenon. Over the long term (back to the early 1960s), there is a strong negative correlation between real yields and the equity risk premium (ERP).

In other words, as bonds get cheaper, stocks get more expensive compared to bonds, and therefore if the Fed manages to hold rates “higher for longer,” stocks can keep richening.

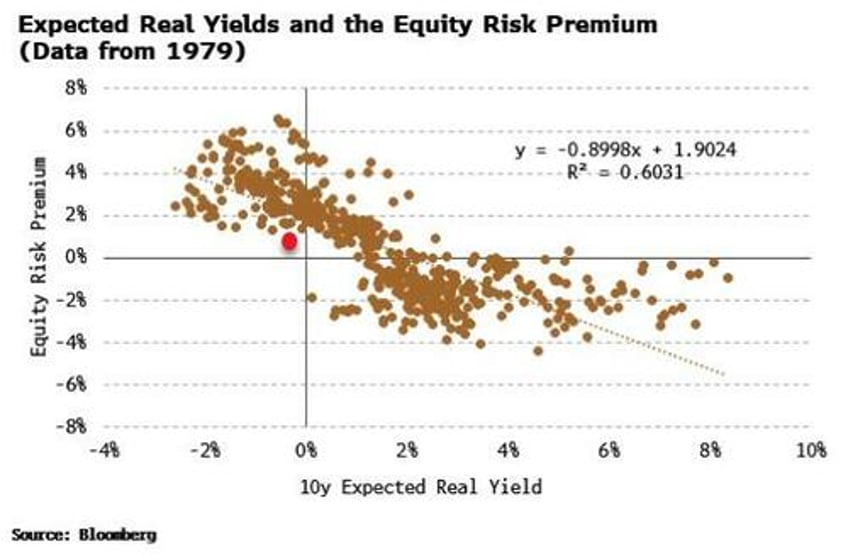

I extended this analysis using expected real yields, defining the 10-year expected real yield as the nominal 10-year yield minus the University of Michigan survey’s measure of five- to 10-year inflation expectations.

What we find is an even stronger relationship, with an R2 of 60% (versus 52% for the original data set over the same historical period), i.e. expectations of how cheap bonds will be is a very good indication of the richness of stocks.

A twist, though, is captured by the set of points to the right of the trend line, when expected real yields were greater than ~6%. Here, bonds were expected to get cheaper, but stocks were not richening as much as the relationship would anticipate.

These data points pertain to the early 1980s when Volcker was catapulting rates higher. At some point, bonds were expected to get so cheap, i.e. for rates to get so high – and so volatile – that owning equities was not attractive either. The ERP did not start falling again until the summer of 1982 – when it was clear bond yields had peaked - with equities bottoming in price terms not long after.

But we’re far from that point yet, and with expected real yields still low today (red dot in the chart above), there is plenty of scope for them to keep rising and for stocks to richen further.

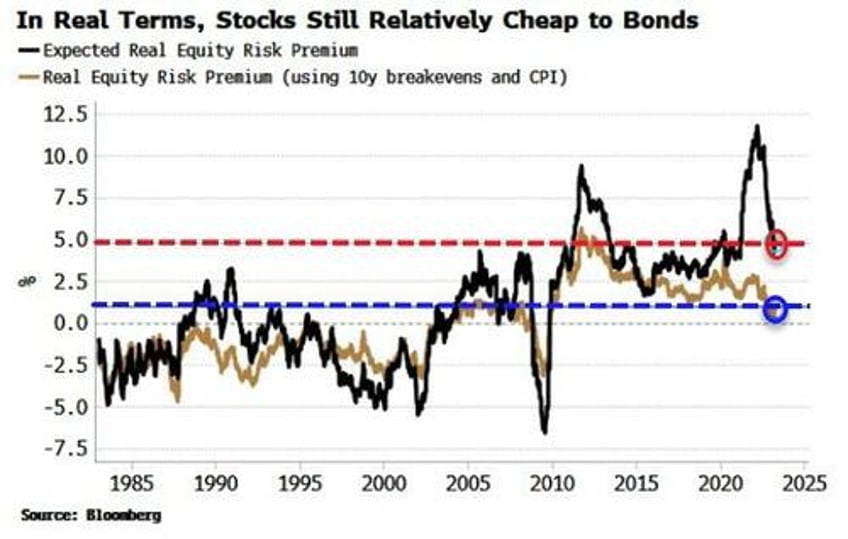

It’s the same takeaway if we look at the ERP on an expected basis. Deflating stocks using long-term inflation expectations (as they are a long-duration asset), and deflating bonds using short-term expectations, we can create an expected ERP.

The chart below shows that while equities are as rich as they have been relative to bonds since the GFC on a real basis, on an expectations basis, their overvaluation is not yet as stretched.

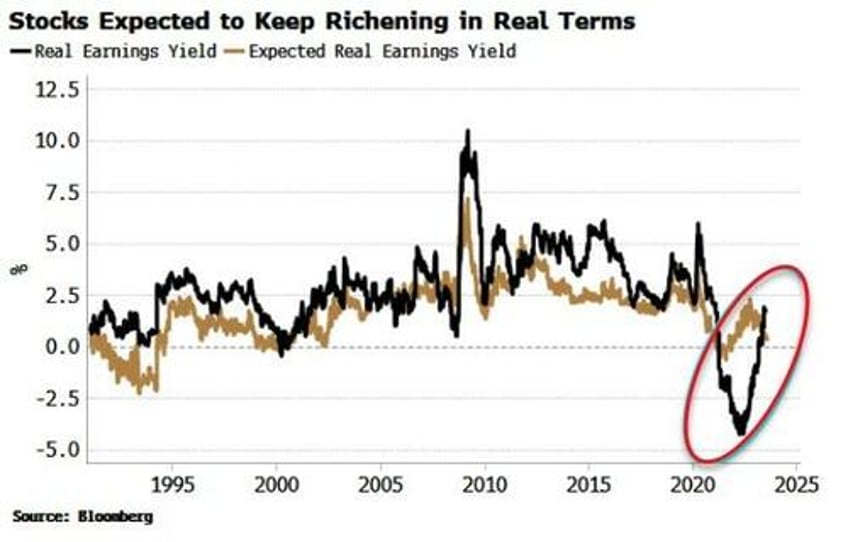

Moreover, this also applies to stocks on an absolute basis. Even though the real earnings yield of the S&P is rising sharply, signifying stocks in real terms are cheapening, on an expected real basis they are richening. This is consistent with the message from the 12-month forward earnings yield which shows stocks are expected to richen in nominal terms.

The extent to which inflation expectations catch up with spot inflation in the coming months will dictate how long the divergence between the expected and real earnings yield can persist, and therefore by how much further stocks can richen. But expectations can be very sticky. They remained stubbornly higher than spot inflation through the 1980s, long after the Volcker rate shock had subsided.

This exercise is a reminder that in an inflationary world, we can no longer assume that real and nominal variables are indistinguishable. It’s real returns that matter at the end of the day, and more importantly the real returns that are expected – and on that basis stocks can keep richening beyond what a conventional nominal analysis would indicate.