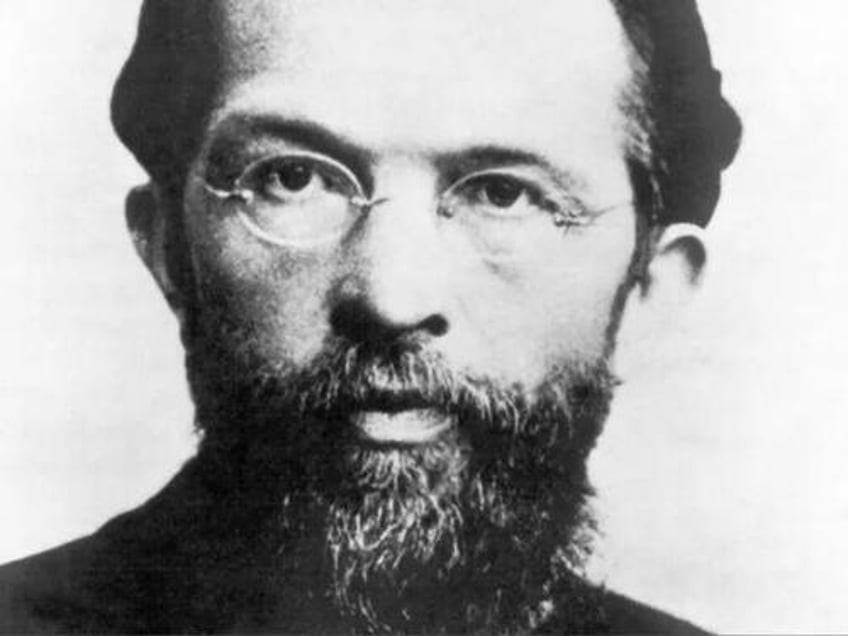

Carl Menger's Overlooked Vital Evolutionary Insights

Carl Menger is widely recognized as one of the economists leading the so-called marginalist revolution along with William Stanley Jevons and Léon Walras. There are two other contributions by Menger that are relatively underappreciated and are vital for making sense of the socioeconomic order, including why mankind remains so lost in economic ignorance and tribalistic warmongering.

They are, first, his insights into the proper method or way to study the economy or social order and its emergence-evolution, and second, his application of such wisdom to explain the evolution of money and the entire socioeconomic order that further emerges thanks to money. Let’s further expand on these two.

Menger wrote an entire book devoted to discussing the proper method with which to study the social sciences, aptly titled Investigations into the Methods of the Social Sciences. So how should we study the social sciences according to Menger? He writes,

Natural organisms almost without exception exhibit, when closely observed, a really admirable functionality of all parts with respect to the whole, a functionality which is not, however, the result of human calculation, but of a natural process. Similarly we can observe in numerous social institutions a strikingly apparent functionality with respect to the whole. But with closer consideration they still do not prove to be the result of an intention aimed at this purpose, Le., the result of an agreement of members of society or of positive legislation. They, too, present themselves to us rather as “natural” products (in a certain sense), as unintended results of historical development. One needs, e.g., only to think of the phenomenon of money, an institution which to so great a measure serves the welfare of society, and yet in most nations, by far, is by no means the result of an agreement directed at its establishment as a social institution, or of positive legislation, but is the unintended product of historical development. One needs only to think of law, of language, of the origin of markets, the origin of communities and of states, etc. Now if social phenomena and natural organisms exhibit analogies with respect to their nature, their origin, and their function, it is at once clear that this fact cannot remain without influence on the method of research in the field of the social sciences in general and economics in particular. . . . Now if state, society, economy, etc., are conceived of as organisms, or as structures analogous to them, the notion of following directions of research in the realm of social phenomena similar to those followed in the realm of organic nature readily suggests itself. The above analogy leads to the idea of theoretical social sciences analogous to those which are the result of theoretical research in the realm of the physico-organic world, to the conception of an anatomy and physiology of “social organisms” of state, society, economy, etc.

Like Herbert Spencer, his contemporary and arguably the most famous and influential intellectual of the late 1800s, Menger too felt like the social order was akin to a “social organism” and should be studied using an organic or evolutionary approach similar to how we study the biological order. Menger thus felt like the methods of the physical sciences, like their use of mathematics, was as inappropriate for understanding the monumental complexity and evolution of the social order as it was for the biological one.

He writes, “I do not belong to the believers in the mathematical method as a way to deal with our science. . . . Mathematics is not a method for . . . economic research.”

Ludwig von Mises and F.A. Hayek would of course follow suit. Mises wrote, “As a method of economic analysis econometrics is a childish play with figures that does not contribute anything to the elucidation of the problems of economic reality.”

Hayek also ridicules the “extensive use of mathematics, which must always impress politicians lacking any mathematical education, and which is really the nearest thing to the practice of magic that occurs among professional economists.”

The following analogy helps us further understand Menger’s vital insights.

Just like the human body organism and the numerous “systems” that coordinate it—like the respiratory-nervous-digestive systems—are the result of the actions of some seventy trillion human and bacterial cells but obviously NOT the result of any conscious planning or designing by them. And thanks to the likes of Darwin and a modern understanding of genetics, we can hypothesize how natural selection was the inadvertent “designer” of such systems and complex order. The modern global socioeconomic order—“social organism”—is also coordinated by a system, by what Menger’s intellectual descendants like Ludwig von Mises and his great protégé 1974 Nobel laureate in economics F.A. Hayek referred to as “the market process.” The market process is composed of “parts” like money, prices, economic competition, interest rates, and the legal-religious-governmental frameworks that sustain it. However, the result of the actions of men “do not prove to be the result of an intention aimed at this purpose . . . but is the unintended product of historical development,” similar to how cells inadvertently and unconsciously acted to create the systems that coordinate multicellular life.

The above mindset or “method” allowed Menger to then make what is arguably the most important insight, or what I like to call the “flux-capacitor” idea, of the social sciences: Menger’s explanation of the evolution of money and its numerous ramifications. Consider the following: from the tradition of private property emerges the freedom to trade it with anyone in the entire planet which inadvertently transforms mankind into a global supercomputer where people via the private companies they create are motivated to innovate and learn from each other (competitors), thus inadvertently cooperating to discover and spread superior information and subsequent order throughout the world.

Money is what enables this civilization-creating mechanism. Every social-order entity, whether a person or a company, is in a constant cycle of the production and consumption of wealth. A business’s sales revenue or a worker’s paycheck is an estimate of how much wealth was produced, and costs are an estimate of how much wealth was consumed while production took place. If there is more production (sales revenue) than consumption (costs), then the order is profitable and has thus increased the economic pie of wealth.

Money is what allows the profit-loss calculation that allows billions of people and companies to order their actions in a profitable and thus pie-order-increasing manner. Also, without money, how would a heart surgeon trade his services for a toothpick? Everything mentioned above that plays a vital role in creating civilization or “the social organism” ultimately depends on and emerges from the use of money. Economics students quickly learn how money is what overcomes the “double coincidence of wants” problem that allows trade and its vital benefits like the ever-expanding division of labor and information to arise.

Without money there is no complex division of labor or information above the levels of small tribes, and thus no large-scale civilization or “social organism.” Menger’s vital insight regarding money is that he showed how money, just like language, was an evolved and NOT designed innovation. Since money was an evolved and NOT designed innovation, this also means that all the other vital mechanisms that, taken together, make up the market process like profit-loss calculation and economic competition, they too are largely evolved/undesigned mechanisms.

This is the key to understanding how we live in this massively complex world, with a rapidly expanding and intensifying division of labor and information that creates mind-bogglingly complex microchips, the internet, etc. Yet the masses and their politicians remain economically ignorant, segregating themselves into us versus them, using the technology to fight deadlier wars, and ignorantly attempting to centrally plan the social-order economy, which inadvertently destroys the evolved and undesigned economic competition which is what really creates and spreads the information that creates civilization.

The above insights and more associated with Menger’s Austrian School of Economics, as Hayek tells us, “belong fully and wholly to Carl Menger.” Hayek again said, “There must be few instances . . . where the works of an author who revolutionized the body of an already well-developed science and who has been generally recognized to have done so, have remained so little known as those of Carl Menger.”

Yes! And we are running out of time to catch up to Menger. It took a while for the vital myth-shattering ideas of Galileo, Bruno, and Copernicus to spread. We find ourselves in a similar situation.

Whether homo sapiens ultimately self-destroy in another tribalistic world war, socialist revolution, environmental disaster, or covid-mania, self-mutilating economic lockdown, it will all come down to whether Menger’s ideas reach people of influence in time.