Four years ago, we wrote an article, mocking the unspeakable reality that it appeared "The Fed and The Treasury had now merged"...

Last week, that reality dawned on one of Wall Street's best and brightest as BofA Chief Investment Strategist Michael Hartnett headlined his latest note with a 'zeitgeist' quote that sounded awfully familiar:

"Biggest piece of M&A in past 12 months was the merger of Treasury & Fed.”

And this morning, Bloomberg macro strategist Simon White takes up the story below, noting that monetary and fiscal policy in the US is becoming more intertwined as the Federal Reserve and the Treasury - implicitly or otherwise - increasingly coordinate their actions.

That’s a structural negative for US Treasuries, and signals an end to the long underperformance of commodities and other real assets.

Reflecting on the quote above Michael Hartnett of BofA - describing the greater coordination of fiscal and monetary policy in the US and the winnowing away of the Fed’s independence from the Treasury - White agrees that, viewed as an M&A deal, it’s certainly massive, given the Fed’s $7 trillion balance sheet and the government’s $34 trillion of debt.

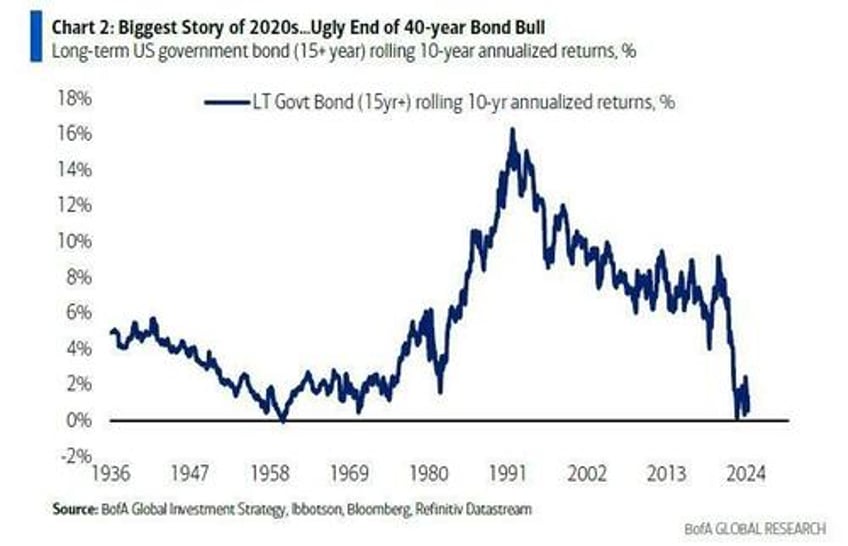

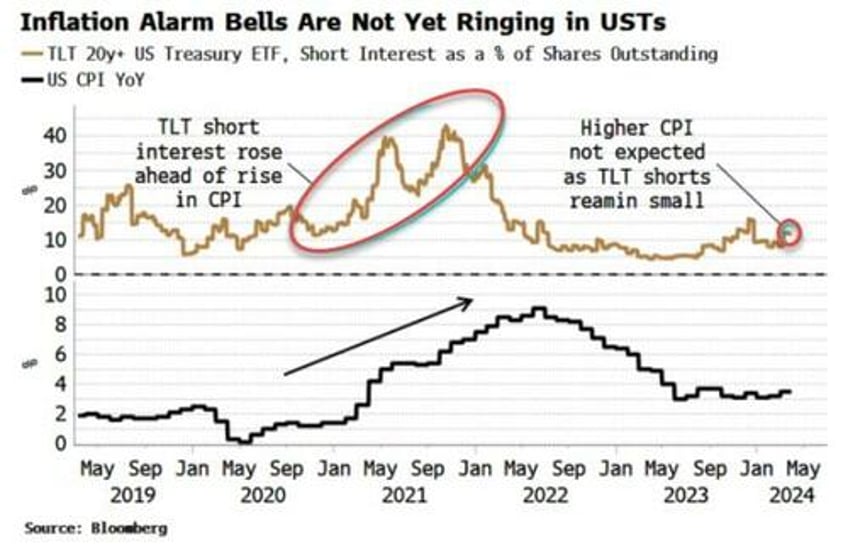

More importantly, it’s hazardous for Treasuries as it tilts the risks for persistently higher inflation firmly to the upside, even though the market continues to be under-appreciative of the ever-more malign landscape. Positioning in USTs has fallen this year, but it is still likely to be net long, while outright shorts remain near survey lows, corroborated by the muted short interest in Treasury ETFs such as the TLT.

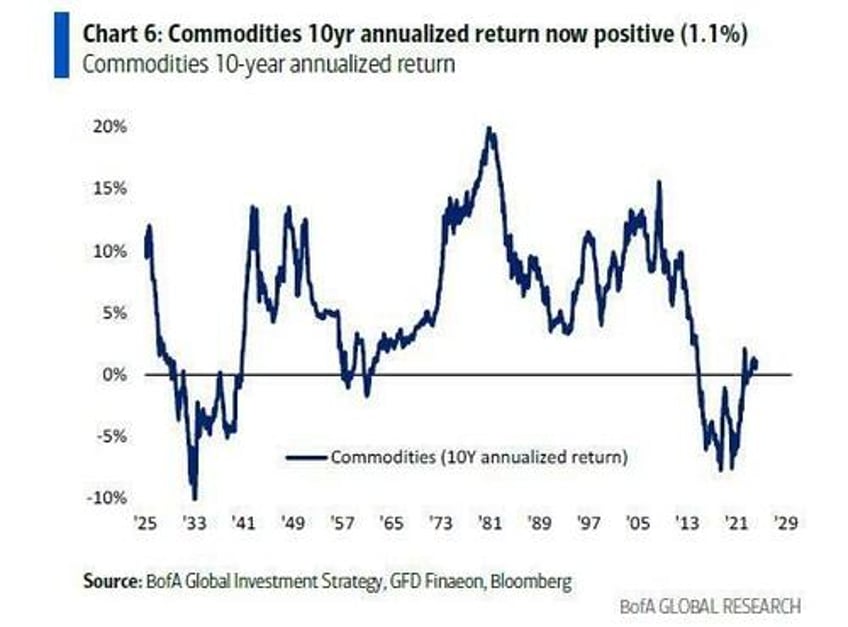

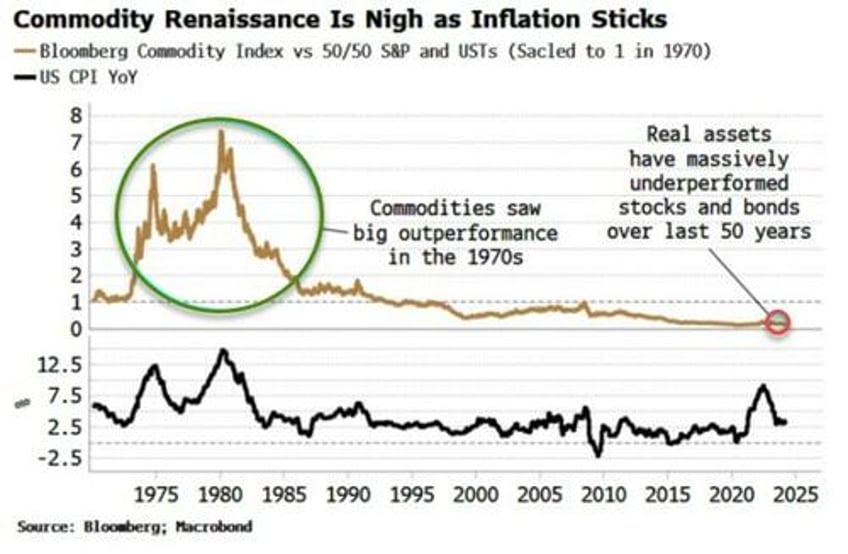

At the same time as entrenched inflation is bad for fixed income, it’s also very positive for real assets such as commodities. They have relentlessly underperformed financial assets - stocks and bonds - over the last four decades.

Governments are inherently inflationary. Wealth is very unevenly distributed, with many dollars held in only a few hands. But every person has exactly one vote. Thus there is an incentive for governments to take wealth from the rich — where it is mainly saved — and redistribute it to the less well-off, where it is more likely to be spent.

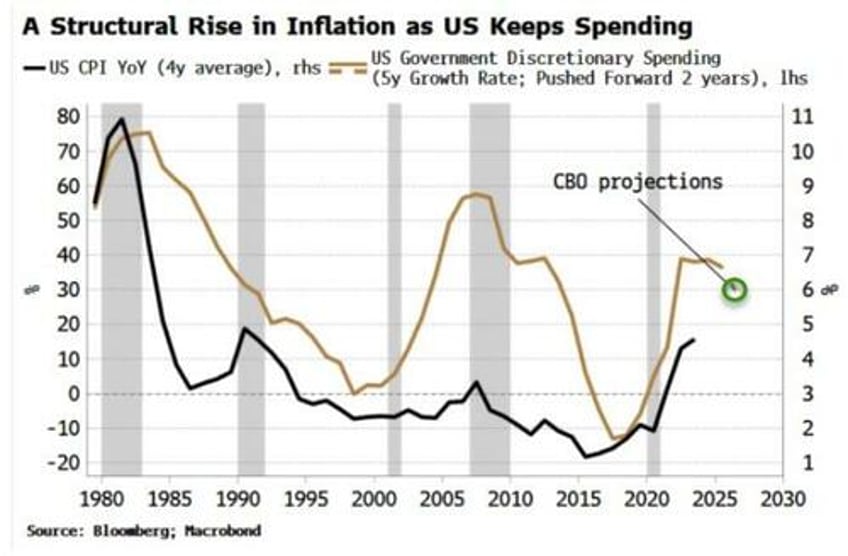

The sort of spending governments engage in in the run-up to elections is likely to be discretionary and debt-funded — which government wants to raise taxes ahead of a vote? Mandatory spending, such as entitlement programs and defense, is likely to see its biggest boost when the economy is in a slump. Increases in discretionary spending, on the other hand, more often than not happen when the economy is growing, and therefore are more likely to fan inflation.

Discretionary spending in the US had already started to grow before the pandemic, and its five-year growth rate has leveled off at an elevated level and not yet fallen. As the chart below shows, longer-term rises in discretionary spending precede structural rises in inflation. Today’s spending is the largest ever seen in the US outside of war or recession.

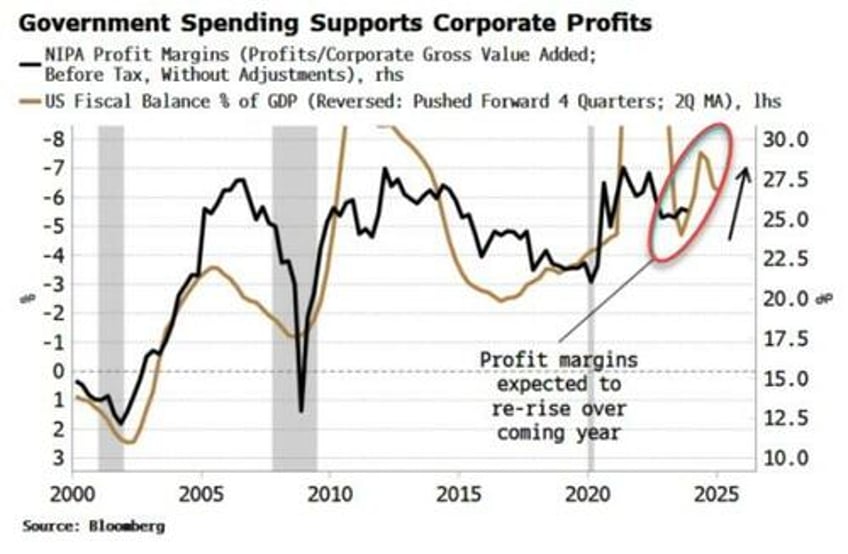

How is government spending stoking inflation in this cycle? Mainly through supporting corporate profits. Deeper fiscal deficits lead to higher profits and profit margins (see chart below), as net spending in one sector must lead to net saving in the others, with the corporate sector the main beneficiary as government deficits support spending in the household sector.

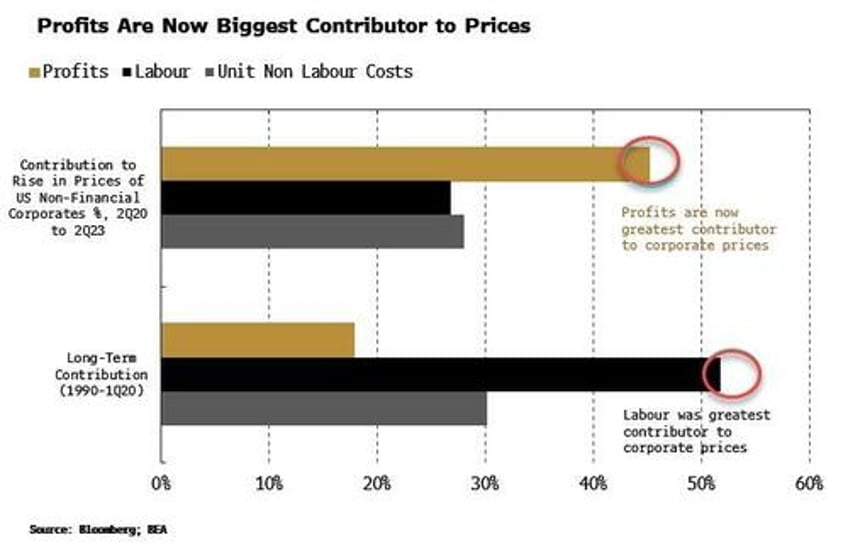

This is a marked change from the 1970s when wages directly drove prices higher. With much less trade-union membership and weakened union power, that’s less of a risk today.

But profits are lining up to be the main vector of persistent and elevated inflation in this cycle. The unique conditions of the pandemic allowed firms to raise profit margins almost as fast as they ever have done. A profit-price-wage spiral is a greater likelihood, and could already be underway.

The risk is that an increase in margins leads to higher prices and then to higher wages. Margins are increased again, but to a greater level than before, to maintain profits in real terms as prices have risen since the last increase.

Economy-wide margins are off their recent highs, but are still significantly elevated compared to their pre-pandemic levels. Labor costs in the decades running up until 2020 made up the bulk of corporate prices, accounting for over half of them on average. But that relationship has inverted since the pandemic, with profits now making up 45% of selling prices, versus under 30% for the cost of labor. Profits now drive prices.

Elevated government deficits can keep the carousel going by supporting spending. The CBO projects discretionary outlay’s five-year growth rate should fall back toward 10% in the next few years from over 35% now. But that’s smoking hopium. The expectations electorates have from their governments markedly rose in the pandemic, with the sovereign expected to underwrite an ever widening basket of risks. The “fiscal put” is becoming embedded and the longer spending keeps rising to pay for it, the harder it will be to reverse.

Government borrowing to fund discretionary spending is a highly inflationary mix on its own, but the addition of a compliant central bank fans the flames further. Notionally the Fed is still independent, but in actuality its maneuverability is increasingly circumscribed for three reasons:

the large amount of Treasuries outstanding and the rising interest payable on them;

the ungainly size of the Treasury’s account at the Fed;

and the increasing proportion of short-term bills, i.e. short-term liabilities that are very money-like.

History is replete with examples of large government deficits monetized by central banks preceding high or hyper-inflation, from China in the late 1940s, to Greece in the early 40s and to Zimbabwe early in this century. That’s not to say we should expect the US to see price growth hit such stupefying levels, but to underscore that spendthrift governments and subservient central banks is a terrible combination for price stability.

Treasuries are unlikely to thrive in this environment.

Nothing moves in a straight line, but the net path for yields is likely to be higher in the coming months and years. Embedded inflation is also likely to drive increasing demand for real assets such as property and commodities, ending their decades of underperformance.

Inflation is one of the most regressive of taxes, as well as being one of the hardest to lower. Almost everyone loses when it is elevated. Even though M&A deals are meant to be value creating, this one is likely to be precisely the opposite.