If there’s one takeaway over the last few years it’s that, as none other than Zoltan Pozsar said in late 2022, the Fed put – the casus belli for intervention – is certainly not "dead", but has changed from an explicit support for risk assets to an implied support for the increasingly delicate balance in the supply and demand of Treasuries.

And although we might question whether Powell really killed the Greenspan put or just deferred the responsibility over to Yellen and the Treasury, one thing is for sure: when there is panic in funding markets – specifically in Treasuries – officials shoot first then ask questions later. It is and has been, after all, America's golden goose that links together the banking system.

The supply of marketable Treasuries is, for all intents and purposes, unending. And unless there emerges a magical incentive from Washington to normalize the fiscal deficits (which itself is now impossible as it would take a very hard landing, sapping tax receipts which then blows out the deficit), it’s all uphill from here, as this all too familiar chart from the CBO gives a glimpse into:

The obviously more important end to the equation is the demand side – who wants a bond, let alone a trillion dollars worth, maturing in 2054 issued by a country on a self-described unsustainable fiscal path? Not just any bond, but a bond with negative term premium (you currently earn more on short-term bills than on longer-term bonds)? Never mind the inflation uncertainties – who's trading these for a 4% coupon?

It makes little no sense – that is, until you understand how an infamous and growing trade popular with leveraged hedge funds works, and how it provides liquidity to these deep and unpopular tenors.

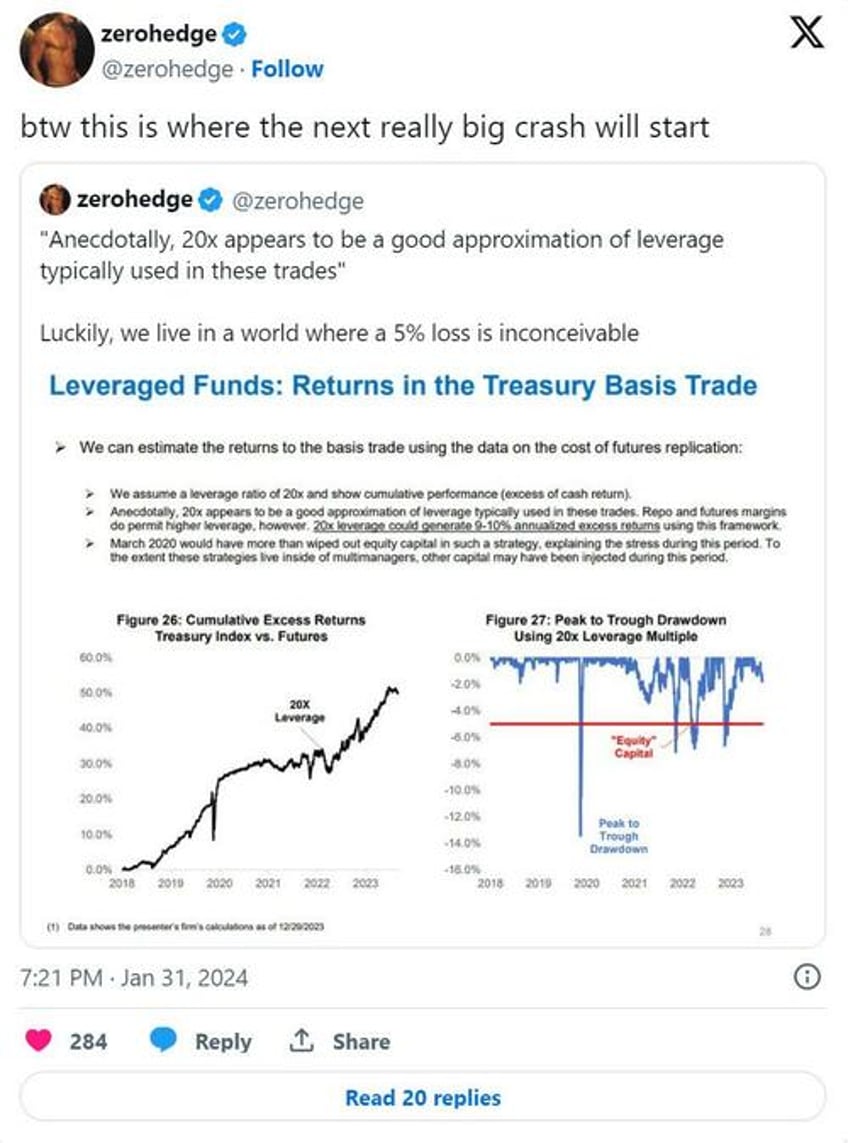

The deluge of long-dated (and notoriously illiquid) Treasuries continues to be absorbed by a cash-futures basis trade taken on in size by domestic and, more recently, foreign hedge funds. While there is no shortage of potential bottlenecks that could “blow it up”, one thing is for sure – the spillover of turmoil in Treasuries to turmoil in, well, *everything else* is magnified by whether or not the basis trade is profitable. Nothing in markets happens in a vacuum – that is to say, "my (stupidly-levered) balance sheet, your problem!"

The (“going long the basis”) trade is a long/short position – long the cash Treasury, and short the Treasury futures – taken on by leveraged funds that seek to harvest the tiny spread between the two (the spread is the literal “cash-futures basis” or “basis”, hence the name). The cash Treasury is financed in the repo market, and this is where they're able to lever-up a tiny profit of singles basis points into something more worthwhile:

- 1) The hedge fund agrees to buy a Treasury in the cash market.

- 2) The hedge fund simultaneously posts that Treasury as collateral in the repo market.

- 3) The hedge fund uses the proceeds from the repo loan to finance the original purchase of the Treasury that it just bought and posted as collateral. The repo loan is for the face value of the Treasury minus a "haircut", so unless the haircut is zero, the rest of the security is financed by the hedge fund's own capital, allowing for quite dramatic leverage when the haircut is small.

The one difference is that, unlike most other long/short strategies, the leveraged funds are not taking any directional risk by shorting the futures, just the risk that the basis will converge to zero before it's time to deliver the Treasury onto the futures contract at maturity.

It always does, but that doesn't mean it can't blow out in the meantime which, if you're leveraged 20x or more, would be catastrophic.

The "basis" exists because asset managers get their Treasury exposure by buying the futures, thus slightly raising the price of Treasury futures relative to cash Treasuries. Asset managers prefer Treasury futures over cash Treasuries because they are operationally simpler and have less impact on their expense ratios.

Rather than buy Treasury futures, a manager could instead repo (lend) out its Treasury holdings and use the proceeds finance other investments. But many active managers are not set-up for repo, and repo loans incur interest expense that raises their expense ratios. So managers instead sell some of their cash Treasuries outright and use the proceeds to finance other investments, and then add back the Treasury exposure through futures.

And, most importantly, this means that while the trade depends on the capacity and willingness of dealers and hedge funds, it also depends on continued investment by asset managers in Treasury futures. TBAC presented research back in January suggesting that said managers use futures only to maintain interest rate exposure, all while increasing their allocation to higher yielding credit investments.

In other words, it's the asset managers who hold the risk to the basis.

In an example from TBAC, an active manager benchmarked to the Bloomberg Agg – the biggest and most widely recognized bond index – could attempt to beat the benchmark by underweighting cash Treasuries and overweighting higher yielding products. The manager then uses Treasury futures to maintain the same interest rate exposure ("duration") as the Bloomberg Agg, whose single largest return driver is interest rate risk:

A segment of asset managers have done just fine through leveraged exposure to Treasuries and overweighting credit, but that positioning now more directly links the two markets together.

Losses on credit products (such as corporate bonds) would lead to deleveraging in Treasury futures as managers de-gross and retrench. Deleveraging in Treasury futures is bound to narrow the basis, seeing demand for cash Treasuries evaporate because there's no basis to harvest.

The other end of it is that it could lead to liquidity squeezes and a wider the basis if managers decide to meet redemptions by selling their Treasuries, as corporate bond markets are by far the least liquid and thus far more difficult to raise cash from.

While liquidity in MBS is just slightly worse than Treasuries, corporate bond market liquidity is abysmal. There are about $11 trillion in outstanding corporate bonds, but daily cash volumes are under $30b. It would be difficult to liquidate large amounts of corporate bonds in typical market conditions, and next to impossible during times of market stress. This was seen in March 2020 and the corporate bond universe has only grown much bigger since. The corporate credit facilities that saved the day in 2020 were not standing but temporary, so that episode will repeat.

For the naysayers and "Nothing-Ever-Happens" fans who will insist it's just speculative hype, we did already watch a preview of this unfold last March when a string of bank failures soured credit conditions enough to see asset managers retrench their futures positions, sending volatility in the Treasury market soaring as the basis started to unwind.

Those who knew where to look would've seen yields collapse in a classic, anxious "safe-haven bid," though under the hood all wouldn't be well as MOVE (Treasury market volatility) spiked far above even March 2020 highs:

Yields are unable to tell the full story...

~

Hedge funds are providing marginal liquidity to the all-important Treasury market via the basis trade. While the trade can unwind due to dealer's inability to hold (and hence repo finance) securities for hedge fund buyers, or from hedge funds unwilling to buy due to regulation, for now, the risk lies with the asset managers who buy Treasury futures to maintain interest rate exposure.

Losses on their credit investments would see them reduce duration by selling Treasury futures, which narrows the (already-tight) basis and imply less participation in the trade – which is less buyers for cash Treasuries. Alternatively, asset managers could sell the more liquid cash Treasuries they hold to raise cash instead of realizing any losses on credit – which would widen the basis as the cash price falls faster than the futures price. Both were observed to different extents during the March 2023 bank panic, and only the BTFP stopped the basis trade from unraveling completely.

These numbers may seem small, and they are, but this is a trade where a single basis point could mean the difference between it being worthwhile buying illiquid Treasuries or not, which itself has an enormous impact on market depth and other funding stresses.

~

The big picture is that the entire Treasury market is structurally illiquid and vulnerable to every tremor, only growing increasingly so as the supply of debt expands. This will be resolved by first exempting Treasuries from leverage ratios and giving banks bottomless balance sheets, but ultimately, a standing role where the Fed makes markets in Treasuries is all but assured. These "quick regulatory changes" won't come without the underlying problem exposing itself, however, like was the case in March 2020 and in other panics since.