They didn’t need to chase this storm, hunt this hurricane, it was already there—bigger and badder than anything seen before at this time of year, this far out in the Atlantic.

Cmdr. Brett Copare knew he was flying into history on June 30 as he steered the P-3 Orion “Kermit” nose-first into a churning wall of towering thunderheads ringing a 450-mile maelstrom that was but a radar flyspeck 48 hours earlier.

“Before we got out there, it was already a Cat 4,” he said, recalling being “awe-struck” and thinking, “A storm this big, this fast … this is unique.”

That flight of unwelcome discovery was one of dozens made by National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) aircrews in tracking the Atlantic’s first-ever June category 4 and 5 hurricane as Beryl launched its 6,000-mile, two-week romp from Cabo Verde to Vermont.

On his third day of standby July 11 at NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center (AOC) at Lakeland Linder International Airport in central Florida, Cmdr. Copare pondered lessons learned—and questions raised—by a storm that “happened so fast,” and was unlike any of the 25 hurricanes he’s flown through.

“Typically, when storms form, we see them when they are at their lowest status, a low-pressure disturbance, and monitor as they gear up,” he said. “This was the reverse of what we normally observe.”

On this haze-gray day, technicians calibrate instruments inside two Lockheed WP-3D Orions—modified U.S. Navy submarine chasers—parked on the tarmac under a gauzy sun.

Inside the AOC’s hangars, mechanics tend to a Gulfstream G-4 and De Havilland Twin Otter while in offices above, meteorologists and scientists ferret through data from storms’ past and monitor National Hurricane Center radar for storms to come.

All are set to go at a moment’s notice. And after Beryl’s rapid intensification, all are aware that notice could come any moment.

“Currently, there’s nothing out there,” NOAA meteorologist and flight director Sofia de Solo said. The lull comes after she flew three G-4 Beryl missions in 10 days.

“As meteorologists, our job doesn’t end when a mission is completed,” Ms. De Solo said, explaining there’s data to review, instruments to fine-tune, and quality control systems to analyze.

But while she “wouldn’t say it’s boring,” standby is not what she says she’s here to do—that being, ride “a scientific laboratory in the sky” to collect real-time data to save lives.

From 45,000 feet above, with horizons hemmed only by the planet’s curved roll, storms are disembodied blots spilling across sky blue, sky black, shimmering as “a very bright big white glow,” a pulsating, living literal ball of energy, Ms. De Solo said.

It’s her “dream job” and there’s no place she’d rather be, she said with the derring-do expected of NOAA’s heralded Hurricane Hunters, the fearless pilots and crews who fly into the eyes of hurricanes.

“We’re prepared. It’s going to be a busy year,“ Ms. De Solo said. ”We’re ready to fly.”

Checking her phone for National Hurricane Center alerts, it’s as if she’s alerting the center: “We’re standing by. We’re ready to go.”

Many NOAA Missions

The Hurricane Hunters are the stars, but not the only operators at NOAA’s Office of Marine and Aviation Operations, which moved from MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa to its custom-built Lakeland AOC in June 2017.

On any day, half the AOC’s 20 pilots, 90 scientists and technicians, two dozen mechanics, and 10 aircraft could be tracking tropical depressions in the Caribbean, mapping coastal estuaries, measuring Rocky Mountain snowpack, or flying for the National Geodetic Survey’s GRAV-D project “calculating the intensity of gravity.”

Most crews are NOAA civilian employees or contractors, but pilots are members of NOAA’s Commissioned Officer Corps, the smallest of eight U.S. federal uniformed services.

NOAA Corp’s 320 officers—there are no enlisted ranks—man 15 research/survey ships and fly specialized data-collecting aircraft, such as those housed at the Lakeland AOC.

A Department of Commerce agency, NOAA coordinates storm-tracking with C-130 “Hurricane Hunter” flights by the U.S. Air Force’s 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, based in Biloxi, Mississippi.

Like many Hurricane Hunter pilots, Cmdr. Copare is a former military aviator. Before transferring to NOAA, he flew Navy “long leg” surveillance/antisubmarine P-3s.

Entering his fourth season, he’s tallied at least 140 “hurricane penetrations, or “pennies,” he estimates, piloting Orions older than their crews straight into storms beginning with Cat 4 Hurricane Ida in 2021.

NOAA’s two P-3s—their fuselages festooned with Kermit and Miss Piggy stencils personally crafted by Muppeteer creator Jim Henson—have flown through more than 100 hurricanes since 1976.

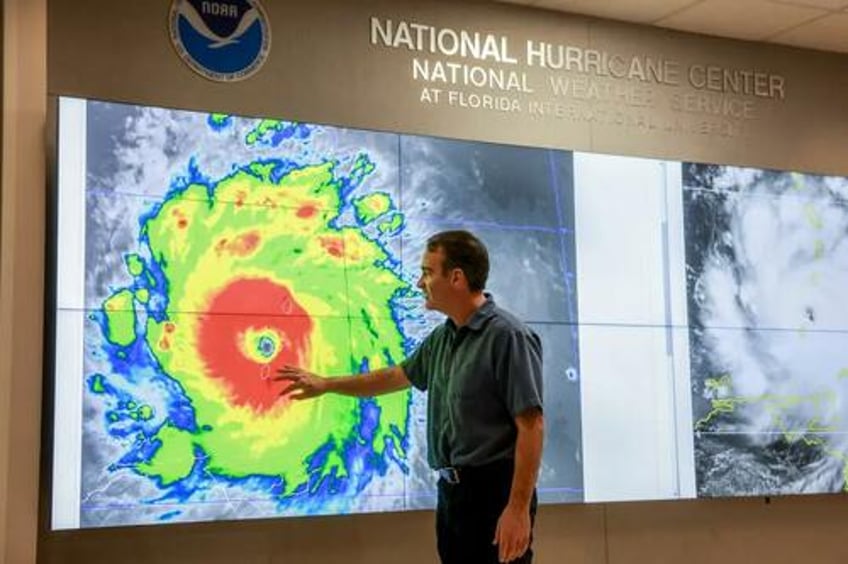

During eight-to-10-hour missions, their 18-to-20 member crews of three pilots, navigators, engineers, technicians, and flight meteorologists, are locked into “Setting 5” work-station harnesses, chart air chemistry, barometric changes, wind speeds, temperature shifts, updrafts, downdrafts, and all the mayhem between in real-time transmit to the National Hurricane Center.

Much data is collected by dropwindsondes, Pringles can-shaped probes that measure wind, temperature, humidity, and pressure as it parachutes through a storm.

Ms. De Solo said she deploys about 30 every mission aboard “Gonzo,” the G-4 also sporting an original Henson stencil.

While crews collect data, pilots plot the storm’s track by flying Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) patterns, or “quadrant-to-quadrant butterflies and circle-eights,” Cmdr. Copare said.

“We start at one corner of the storm, make three to four passes through the core,” he said. “Then, back in. The aim is to find the center path by dead reckoning, each fix to each fix.”

Each “penny to penny” pass at 8,000-to-10,000 feet can take an hour with P-3s usually making three to four every mission.

NOAA provides simulations and training, but replicating a flight through a 120-mph slipstream of fury in a careening canister is hard to do.

“There’s really no way to prepare yourself for what that’s going to be like,” Cmdr. Copare said, noting as the battered plane bounces and heaves, there’s an out-of-body sense with the windshield obscured by rain, all sound blurred in a thunderous, rattling roar, and two-handed focus on cockpit controls.

He recited the mantra repeated since a B-25 Mitchell bomber crew first successfully flew through a hurricane in 1943 because it’s still the best way to describe it.

“It’s like riding a roller coaster through a washing machine,” Cmdr. Copare said.

Read more here...