On her first day after moving from Australia to the United States, Elizabeth Dunford walked into a supermarket to buy bread. As a researcher of food additives, she instinctively glanced at the ingredients label.

“Why are there so many additives?” she exclaimed in surprise. Nearly every loaf she picked up contained ingredients that made her uneasy. After lingering by the shelves, she reluctantly chose a bag.

“At that moment, I thought: It looks like I will have to choose the best from the worst when shopping in the future,” Ms. Dunford, project consultant for The George Institute for Global Health and adjunct assistant professor in the Department of Nutrition at the University of North Carolina, told The Epoch Times.

Today, over 73 percent of the U.S. food supply is ultra-processed. While both natural and ultra-processed foods are referred to as “food,” there is a vast difference between them. For instance, ultra-processed foods are not grown in soil but manufactured in factories, using many ingredients that cannot be found in the average home pantry.

Beyond conventional additives such as preservatives, colors, and flavorings, many new additives are emerging. Stabilizers, emulsifiers, firming agents, leavening agents, anti-caking agents, humectants, and more have been invented to modify and improve the taste and texture of food.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) lists at least 3,972 substances added to food.

Perhaps driven by a growing desire for richer and more varied flavors or by the pressures of fast-paced living, people have become accustomed to these substances, even considering them a natural part of the modern diet.

Then and Now

In the old days, families used salt and vinegar to preserve food. But with the advent of the industrial age, people became increasingly reliant on ready-made foods available on supermarket shelves.

“By the mid-20th century, more and more food additives were being used,” said Mona Calvo, who has a doctorate in nutritional sciences and is an adjunct professor in the Department of Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Only recently have people begun to pay closer attention to what goes into the foods they eat.

In the 1950s to 1970s, the FDA began evaluating the safety of common food additives, Ms. Calvo told The Epoch Times.

“A safety assessment involves the scientific review of all relevant data, including toxicology and dietary exposure information,” an FDA spokesperson told The Epoch Times. These include tests conducted on rodents and cells. The ingredients will be added to food after the FDA gives its approval.

Consumers can identify what is in their packaged foods by the nutrition facts and ingredient labels, said Ms. Calvo.

Among the most widely used FDA-approved substances added to food, many have a safety classification known as “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) based on their extensive historical use before 1958 or their safety evaluation in the 1970s or more recently.

However, many people may not realize that substances classified as GRAS often lack an upper limit on the amount that can be added to food. In many cases, the quantity added is based on Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) guidelines. Ms. Calvo explained that if a manufacturer adds an excessive amount of an additive during production, which makes it unpopular among consumers, it could affect product sales. In other words, the amount of substances added is left to the manufacturer’s discretion.

Over time, GRAS classification may be withdrawn for certain substances if the FDA is presented with compelling evidence of safety concerns associated with its use. A notable example is the official removal of trans fats from the GRAS list in 2015.

Ms. Calvo pointed out another unresolved issue: There is no oversight on how much of these additive-containing foods people actually consume.

“Many of the commonly used food additives were granted GRAS approval between 1970 and 1975, when people could not foresee the situation today,” she said. During that era, fewer women worked outside the home, and people consumed more home-cooked meals made from natural ingredients. With the prevalence of ultra-processed foods in today’s diet, the consumption of certain additives has naturally exceeded initial expectations.

After an additive is approved for a specific function, food manufacturers often quickly incorporate it into a wide range of products, including breads, cookies, instant soups, sausages, and frozen, prepackaged meals.

Dr. Jaime Uribarri, a nephrology specialist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai who has long been concerned about specific food additives, told The Epoch Times that “once an additive-containing packaged food is in the marketplace, the FDA does not have a mechanism for regularly testing its safety, such as through periodic sampling checks.”

The Useful and the Unnecessary

Objectively speaking, some food additives may offer more benefits than drawbacks, said Ms. Dunford.

Preservatives, for example, help extend the shelf life of food. Adding a moderate amount of nitrites to cured meats can prevent botulism, a serious condition.

However, she pointed out that many additives that enhance color, flavor, and other sensory aspects are “essentially not necessary.”

Scientists have demonstrated in various studies the health hazards of consuming ultra-processed foods, including their close association with early death, cardiovascular diseases, mental disorders, respiratory diseases, metabolic syndrome, and cancer.

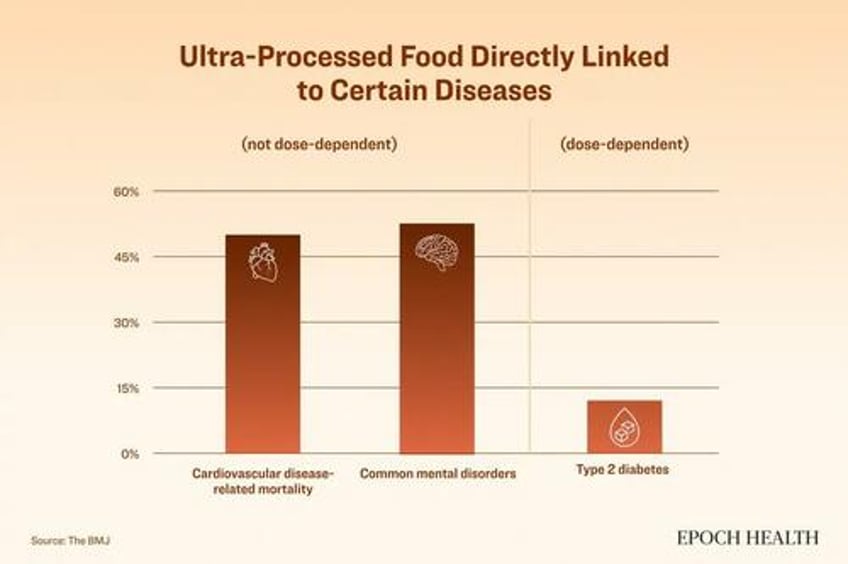

Specifically, a cohort study involving nearly 45,000 middle-aged and older individuals in France found that for every 10 percent increase in the intake of ultra-processed foods, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 14 percent. According to a 2024 umbrella review published in the BMJ, convincing evidence has been found linking ultra-processed food to a 50 percent increase in cardiovascular disease mortality, a 53 percent increase in common mental disorder outcomes, and a dose-dependent 12 percent increase in diabetes risk.

While part of the increased risks can be attributed to the use of high-sugar, high-salt, high-fat, and low-fiber ingredients, some additives previously thought to be safe also warrant attention.

“Phosphate additives is one that I’m very wary of,” said Ms. Dunford.

Phosphate Additives

A 2023 study published in the Journal of Renal Nutrition found that of all the 3,466 U.S. packaged foods tested, over half contained phosphate additives.

Phosphate additives encompass a range of substances with various functions, such as stabilizing, thickening, emulsifying, adjusting acidity and alkalinity, improving texture, enhancing flavor, providing antioxidant properties, preserving, and coloring. Some phosphates serve multiple functions simultaneously.

Multiple studies have shown that the health hazards associated with consuming ultra-processed foods are linked to a high intake of inorganic phosphates.

The body’s absorption rate and utilization efficiency for phosphorus vary depending on the source. When a person eats natural foods, the release of phosphorus is relatively slow, and not all of it is absorbed. In contrast, inorganic phosphate food additives are quickly absorbed into the bloodstream, significantly increasing blood phosphate levels and releasing hormones that promote phosphate excretion. These hormones can have a range of adverse effects on the cardiovascular system, kidneys, and bones, resulting in reduced vitamin D levels, bone loss, vascular calcification, and impaired kidney filtration capacity.

Using inorganic phosphate additives in animal or cell experiments results in immediate side effects. “That gives you enough rationale to suspect that these may happen also in humans,” said Dr. Uribarri.

Read more here...