The lagged effect from central-bank rate rises has yet to fully feed through to markets and the economy, posing a headwind for risk assets in the medium term.

With at least six developed market central banks due to announce rate-setting decisions this week including the Fed, the BOE and the BOJ, it’s a good time to look at where we are the in the global rate-hiking cycle.

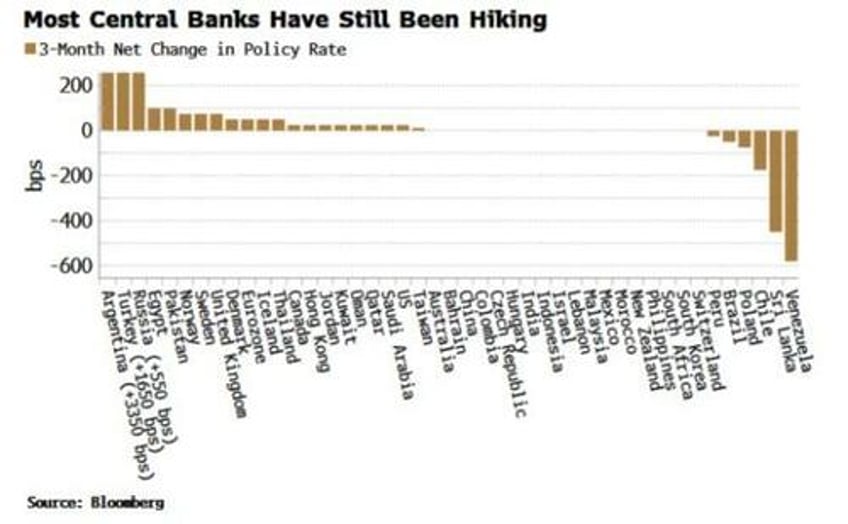

While the Fed is quite possibly done raising rates for now, and the ECB and the BOE are probably within one hike of being so, most central banks are still in the hiking zone. The major exceptions are Poland, Chile and Brazil (the latter’s central bank is expected to cut the Selic rate again this week), where inflation has quietened enough that policymakers can refocus on supporting growth.

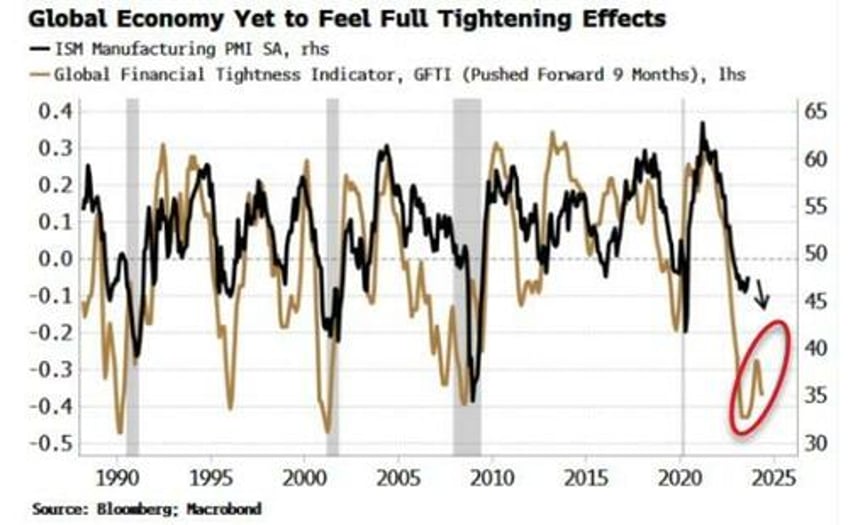

Tighter monetary policy of course takes time to filter through to the market and to the economy. My Global Financial Tightness Indicator (GFTI) is a diffusion of global central bank rate hikes. It had started to turn up – indicating financial conditions should soon loosen – but then has turned back down again, showing that the full tightening impulse has yet to be felt.

As the chart below of the GFTI shows, its turns lead the turns in the US manufacturing ISM by around nine months, and indicates the ISM should go back down again later in the year, or early next year.

The ISM and US and global manufacturing are very important influences on global stock markets.

US manufacturing is a small proportion of GDP, but it is a disproportionately large part of corporate profits and intermediate inputs, and therefore has a significant influence on global stock markets. Its sensitivity to the economic cycle means it typically leads equities.

Global stocks and other risk assets are therefore likely to run into resistance in the medium term, as rate rises filter through directly to stock markets, and indirectly through their impact on the real economy.

However, as always with markets, nothing moves in a straight line, and time lines are important. In the shorter term (< 3 months), the excess-liquidity picture remains constructive for stocks. Excess liquidity is the difference between real money growth and economic growth in dollar terms. The combination of lower inflation and a weaker dollar (compared to a year ago) is keeping excess liquidity, and thus risk assets, supported.