Gov. Ron DeSantis issued a state of emergency for 33 Florida counties on Saturday in anticipation of Hurricane Idalia, thus activating one of the most misguided and counterproductive economic policies imaginable.

Yes, with the sweep of his pen, DeSantis banned “price gouging.”

“I have activated our Price Gouging Hotline to take complaints about extreme price increases on commodities needed to prepare for a potential storm strike,” Attorney General Ashley Moody said in a statement on Saturday.

This will make a lot of people feel better, but it won’t do anything to help the flow of goods and services in the state. In fact, it will create more problems than it solves.

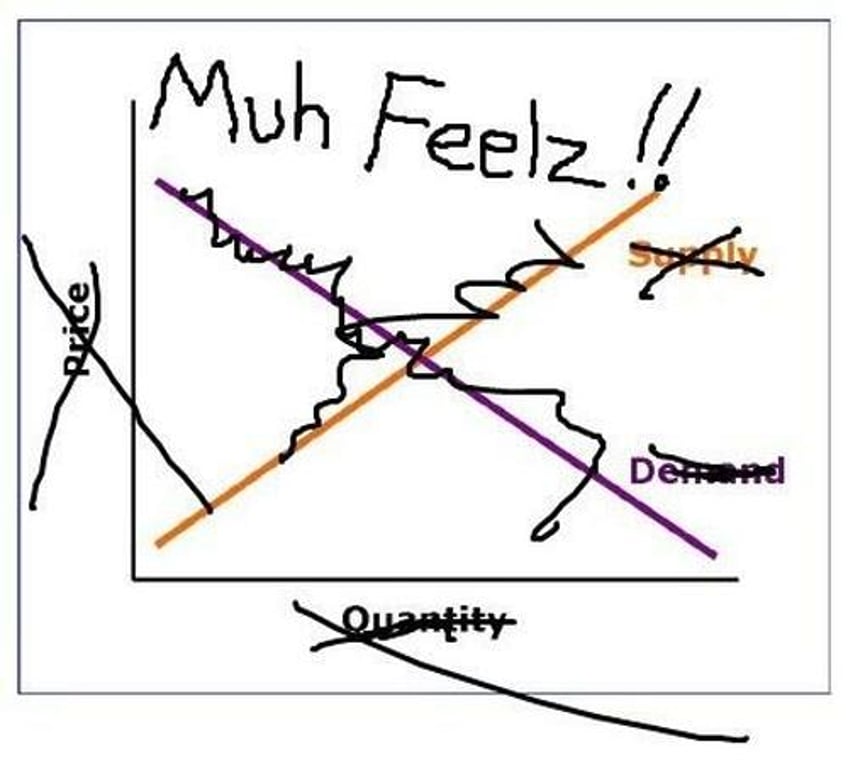

People have a visceral emotional reaction to people raising prices during a disaster. But it is nothing but feelz. In fact, “price gouging” serves an important economic function. Not allowing prices to rise actually causes more harm.

But trying to explain this is like spitting into the wind. (Hurricane pun intended.)

Most people cheer price gouging statutes. After all, they are going after “greedy people” who are taking advantage of other people in difficult situations.

And you know what? Price gougers might be greedy. But that doesn’t mean prices shouldn’t go up during an emergency.

In fact, there are sound economic reasons that so-called price gouging really isn’t such a bad thing. It’s a natural function of supply and demand. Prices rise as demand goes up and supplies tighten. That’s economics 101.

Pretend you know it’s going to rain for a month straight. You would probably buy an umbrella, right? A lot of people would. And that means the price of an umbrella would go up. Now, if umbrella prices stayed really low, say because some knuckleheaded politician passed a law that said you can’t raise the price of an umbrella when the weatherman is predicting rain, you might buy one for each member of your family. But if prices spiked in response to demand, you would probably make do with one or two, leaving some umbrellas for somebody else.

Nice, right?

The rising price would also help boost supply. If umbrellas get expensive enough, some guy in a less rainy locale where there is less umbrella demand might be willing to bring in a shipment of bumbershoots. It would be worth his while to pay higher transportation costs to take advantage of the higher price. But if the knuckleheaded politician has his way, the price won’t rise and our budding umbrella entrepreneur will just stay home and sell sunglasses.

This makes sense, right?

Doesn’t matter.

No matter how much sense it makes, or how you explain it, people will get angry about price gouging. I can’t win this argument. People just react negatively to rising prices during a crisis. Muh feelz trump logic.

Every. Single. Time.

Of course, these same people will pay $12 for a beer at a baseball game. But when you ask them to pay $3 for a bottle of water before a storm, it’s a crime of epic proportions. Never mind that while people are yelling and screaming about “price gouging,” there’s nothing left on the shelf to buy. Too bad there were no price signals to direct supply and demand.

Here’s an important thing to remember. Economic reality doesn’t care about your feelings.

The problem is you can see the results of price gouging. You feel the pain of the higher prices. It’s easy to finger-point at the greedy guy.

Now, you may also feel the pain of shortages. But almost nobody understands that the anti-price gouging policy caused it. There is no obvious cause and effect. So, people just don’t get it. It’s a classic example of economist Frédéric Bastiat’s seen and unseen. Good economists consider both the obvious “seen” effects of a policy as well as the less obvious “unseen” effects.

Unfortunately, most people aren’t good economists.